Brussels, still reeling from the ISIS nail-bomb attacks at Zaventem Airport and Maalbeek metro station in March, was raw and rough around the edges when the time for its scheduled art fairs arrived—the more traditional Art Brussels and the progressive New York transplant Independent. Needless to say, cautionary sentiments preceded all the fanfare this year. Partial closure of the airport’s departure halls and rerouted flights steered away many would-be visitors, while the subways operated at half-capacity with travelers favoring the perceived safety of Uber taxis. The doubling of machine-gun-touting military, Humvees, and tanks patrolling the streets and train stations didn’t necessarily help to calm nerves. Yet the bombings didn’t come as a surprise for many in town, considering the now evident links between disenfranchised radicals in Brussels and Paris. Endemic violence is all too familiar in this polyglot city, rife with racism and economic inequality—both sustained vestiges of its colonial past, riding on the shoulders of contemporary socio-political issues.

Despite the major funding cuts in 2014-2015 to established institutions for dance and theater like La Monnaie, BOZAR, and Beursschouwburg, Brussels’s contemporary visual art scene is flourishing. Why? This is a historic city that offers rich creative fodder, but that’s already a given, even for tourists. A welcoming environment for internationalism and the circulation of money is what it really comes down to. Brussels is a quick train ride from major hubs like London, Paris, Amsterdam, or Düsseldorf, whose highly trained art students have stumbled onto the tracks and fallen out at Gare du Nord. Space is available, rents are relatively cheap, and there’s supportive patronage in the form of an active collector base, helping artists and galleries fund their next projects. “Brussels is the most European city in Europe,” states Independent’s Creative Advisor Matthew Higgs at the fair’s White Columns, New York, booth, commenting on the city’s central location and diversity as primary deciding factors for launching there. What started out as an art fair made for artist audiences has turned into a fair organized by dealers for dealers, who were clearly more excited than anyone else about each other’s booths. Undeterred by the dizzying open-plan format in the Vanderborght building—a former department store—the presentations were immaculate. Material play and an attraction to grit and humor in the abject defined memorable works like David Douard’s sculpture U make me sick (2014) at Galerie Chantal Crousel, Paris, which looked like a cross between a bus shelter covered in advertising, a seedy 1970s living room lined with fake fur, and a haunted house with a motley assemblage of deformed body parts. Simon Preston Gallery, New York, showed a curious group of framed collages (all Untitled, 2016), made by Josh Tonsfeldt primarily with prism film, Hydrocal, and epoxy resin, collapsing visual and material space to ghostly effect as the work’s images disappeared and transformed before one could process their signifiers or even substance. On the ground floor, Zurich’s Galerie Gregor Staiger showed a group of video works by Shana Moulton in which she places herself in the frame of ironic new-age journeys to self-realization and stages confrontations with consumer products marketed for self-betterment.

The fair’s outstanding booths were its most unexpected collaborations. Cahn International, Basel, teamed up with Galerie Jocelyn Wolff, Paris, mixing contemporary sculptures by Guillaume Leblon and Franz Erhard Walther and works on paper by Katinka Bock with antiquities such as a fragment from the statue of an Egyptian god (An Important Colossal Statue, fifteenth to thirteenth century B.C.), fifth century A.D. Roman glass, with a few votive phalli from the fourth to second century B.C. to amp up the sex-factor. And for the light-hearted, there was Le Salon, a curatorial and editorial platform invited by the local Almine Rech Gallery to bring the cat tree project they showed at M HKA in Antwerp, in which artists were invited to respond to John Armleder’s readymade cat tree Untitled (FS) (1997) on their own terms. Amanda Ross-Ho, for example, contributed Untitled Cat Tree (CRADLE) (2016), made of black, oversized cartoonish hands, entangled in thread, playing the children’s game cat’s cradle.

Another Ross-Ho piece of a massive glove showed up in “Not really really,” a group exhibition culled from the collection of Frédéric de Goldschmidt, co-curated by Goldschmidt and Agata Jastrząbek, smartly installed in a former mental health facility. Works from Mona Hatoum to Puppies Puppies found their native homes in every nook and cranny of the worn, un-renovated building. Aside from the fact that the opening was the liveliest of the week’s events, the exhibition was also a prime example of a context that adds aesthetic and conceptual value to artworks as opposed to the problematics of faux-neutral white cubes.

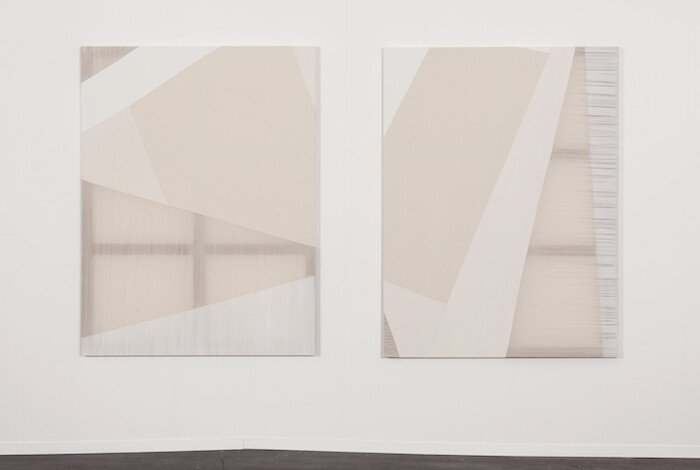

The empty hospital provided a stark contrast against the conservative aisles of Art Brussels, a reminder that art viewing and art buying are two separate experiences. This year’s edition moved to the airy, light-filled Tour & Taxis building, so named after the German noble family Von Thurn und Tassis that ran it as a depot for the imperial post from the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries. Throughout the fair, textile works could be seen in abundance. Perhaps a “return to the real” of physical tactility is displacing the glut of flat, digital surfaces. Or perhaps the trend goes back even further to the Flemish mastery of tapestries in the late-Medieval and Renaissance eras. These days, it’s hard to tell if events before the internet are even still relevant, but I’d like to offer makers, exhibitors, and buyers of these works the benefit of the doubt. Woven works by Mika Tajima at 11R, New York, Yann Gerstberger at Sorry We’re Closed, Brussels, Laure Prouvost at MOT International, London, Eduardo Terrazas at Timothy Taylor, London, and Rebecca Ward at Ronchini Gallery, London, were but a few of the most distinguished.

In an adjacent building, the fair’s Artistic Director Katerina Gregos curated “Cabinet d’Amis: The Accidental Collection of Jan Hoet” as an homage to the late Belgian curator and founder of S.M.A.K. in Ghent. Small works ranging from painting to photography and works on paper hung behind glass. The project offered a sentimental approach to collecting, one based on hard work and friendship. Similarly, at the BOZAR, Daniel Buren’s exhibition “A Fresco” was an elegantly curated selection of significant works that influenced him as an artist, ranging from Mario Merz to Ann Veronica Janssens, posited as a retrospective. Meanwhile, WIELS showed a classical retrospective of Edith Dekyndt about organic decay.

Interest in the applied expression of core sculptural materials continued at composite with Caroline Achaintre’s exhibition of animist ceramic masks and at Rodolphe Janssen with a group show of ghoulish ceramic sculptures called “Made in Oven,” installed in a secret garden-like setting inside the gallery, designed by famed florist Thierry Boutemy. In particular, artists’ relationship to nature and landscape took center stage in the group show “Pastoral Myths” at La Loge, while Mark Dion’s “Reconnaissance” at Waldburger Wouters focused on mankind’s destruction of it.

And yet, after all was said and done, it was Marina Pinsky’s exhibition “POLAR” at Clearing that resounded the most poignantly. Pinsky covered the downstairs rooms with wallpaper including illustrations of the city’s four loci of power—Palais du Justice, Prison de Saint-Gilles, European Parliament, and NATO headquarters, around which are a selection of illustrations of rain made of ropes, playing on the phrase “Il pleut des cordes” (it’s raining ropes, a turn of phrase akin to the English “it’s raining cats and dogs”). In the room stands an empty bank safe whose lock has been blown off. In the upstairs galleries, a sequence of 24 photographs each titled Woman and Child (2016) shows the gloved hands of the police finger printing the acquiescent hand of a child. Pinsky solicits a sense of helplessness, cooperation, remorse, and resistance. We should not blindly trust the powers that be, nor should freedom be taken for granted. A considered moment of pause is in order before taking next steps.