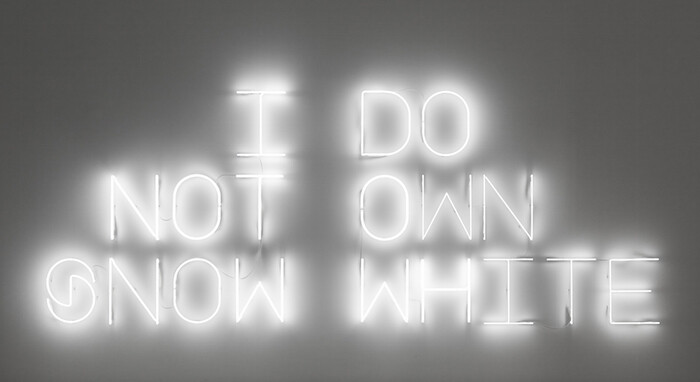

Annlee quietly welcomes you to the Fridericianum’s ticket counter. Though she is still invisible, her voice embraces those standing in the great entrance hall of the museum. “Can you imagine me?” she asks melancholically, “I can imagine you… It’s easy. I can see you. And I can see her.” Her face appears in Pierre Huyghe’s video Two Minutes Out of Time (2000), projected on a big white wall that serves as a screen, visible right after you pass a bright neon sign that reads, I Do Not Own Snow White (2005). Annlee, like Huyghe’s neon, is a never-ending story of copyright and authorship. After purchasing Annlee from a Japanese agency, Huyghe and Philippe Parreno used her image in their works—as in Huyghe’s video, which explores the disembodied space the animated character inhabits, and her multiple personas—and licensed her out to other artists as well.

Curated by Susanne Pfeffer, “Images” is a group show in which images are indeed the artists’ starting point. After encountering Snow White and Annlee, one thinks of image appropriation as it was famously framed in the canonical exhibition “Pictures,” curated by Douglas Crimp for Artists Space, New York, in 1977, which questioned both the possibility and the significance of originality. Authorship and copyright are also at stake in “Images,” though the exhibition focuses on artistic research conducted a few decades after the “Pictures Generation.” Most of the works in “Images” date from the 2000s, when artists had access to digital databases and were experimenting with various software programs. Pfeffer additionally establishes a terminological shift from “picture” to “images” in the exhibition’s title that takes Crimp’s concept a step further. “Underneath each picture,” he wrote in October in 1979, “there is always another picture.”1 But whereas Crimp’s approach turns viewers into historians searching for hidden layers of the past, Pfeffer’s directs viewers towards artists’ vision of the technological future.

Michael Majerus, for example, experimented quite early with computer software, using Photoshop and other programs to design his own works and visualize others’ as mere guidelines. From 1996 to 2002, Majerus copied and quoted the styles of the works of Gerhard Richter and Andy Warhol, combining them with images from popular culture, to produce an untitled series of works on canvas, each measuring 60 by 60 cm. At the Fridericianum, a wall bearing a gridded installation of these canvases shows the way in which they anticipated the contemporary status quo of digital media: images accumulate and circulate without respect to their copyright and value; the pictures’ presentation resembles photo filter programs and photo apps like Instagram. In that sense, Majerus, who died in 2002, was visionary: his work shows how technology informs aesthetics. But it also shows how technology, when it becomes accessible on a mass scale, makes the aesthetic avant-garde look outdated.

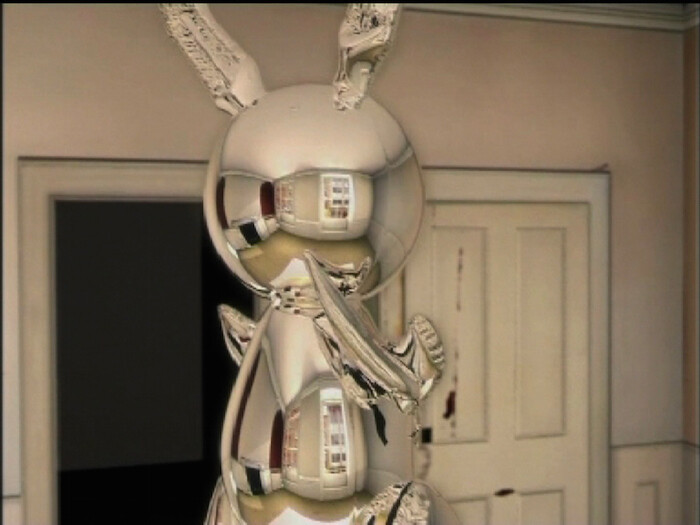

Similarly, political events can irrevocably shape our perception of data: in a way, the show recalls a pre-Snowden era when the belief in a world of free-floating images that have neither an origin nor a destination—an abstract virtual space—was still commonplace. Mark Leckey’s 16mm film Made in ’Eaven (2004) reflects on the dislocating effects of the digital image. Digitally animated with CGI and then transferred to 16mm, the motion of the film’s frame suggests a camera circulating around a copy of Jeff Koons’s Rabbit (1986) in Leckey‘s studio, but the reflection of the sculpture reveals neither cameraman nor spectator—as if the surveilling eye is independent from the physical world.

Walking through the exhibition, one almost feels nostalgic for a time when this kind of simulacra was a primary object of artistic concern. Seth Price’s sculpture Double Hunt (2006), for example, consists of a sheet of clear plastic printed with motifs from the Lascaux Caves in France, which were fully replicated in 1983 in order to save the original Paleolithic cave paintings from damage. Similarly dealing in the abstraction caused by the absence of an original image is Cory Arcangel’s Data Diaries from 2003. In it, 31 videos presented on low-lying monitors show what data looks like when converted incorrectly: a beautiful stream of pixels and abstract color fields.

For artists like Price and Arcangel, code and error, copy and paste were operations of digital media that merited attention and scrutiny; for the generation of younger artists that followed, these concerns were a given starting point. Since becoming Director of the Fridericianum in 2013, Pfeffer has worked to institutionalize post-internet art, dominating the discourse in Germany with a series of three exhibitions: “Speculations on Anonymous Materials” (2013–2014); “nature after nature” (2014); and “Inhuman” (2015). These showed post-internet artists, following the conceptualization of the Anthropocene, responding to technology by asking how it, in turn, affects our bodies and the environment.

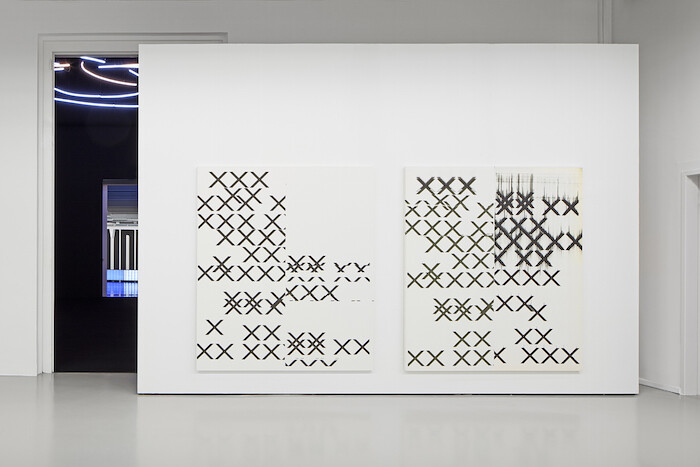

Five of Wade Guyton’s untitled canvases produced between 2006 and 2008 appear in “Images.” To create these conceptual print-paintings, the artist used an inkjet printer to inscribe the letter X onto folded canvases. This gesture recalls the critical genesis of modern painting, replacing color and formal abstraction with a symbol for negation or confirmation, a variable in an equation, and a multiplication sign. Viewing this series in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis brings attention to the critical possibilities it prefigures, but which were subsequently rejected by younger painters whose work has given way to absurd speculation under the umbrella of zombie formalism.

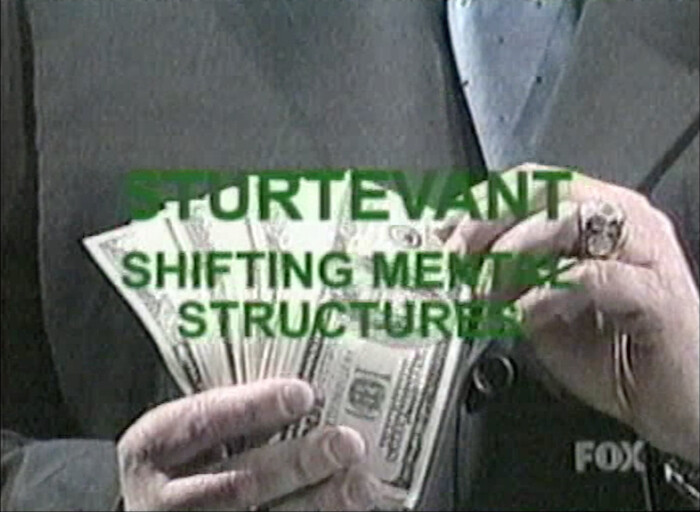

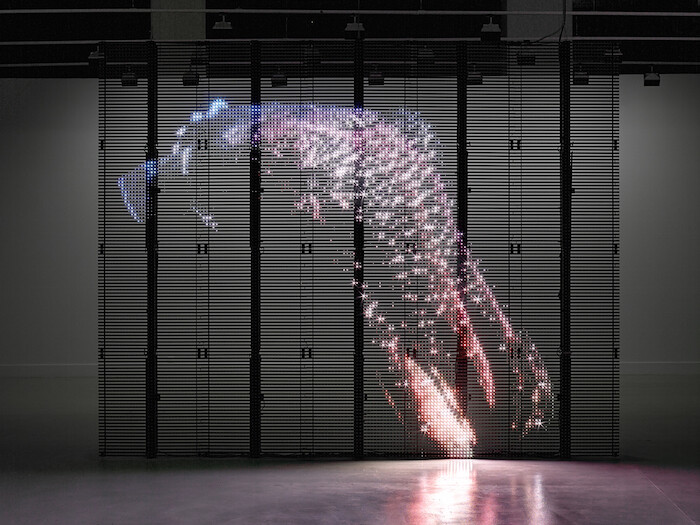

In this respect “Images” is not just a retrospective of a famous few, Sturtevant and Trisha Donelly also among them. It is rather a byproduct of Pfeffer’s impressive research—a representation of what data-based artwork, maneuvering between copyright and authorship, image and imagination, looked like in the past: like a hopeful future. In Philippe Parreno’s video No More Reality, la manifestation (1991), shown here on a large LED screen, children are recorded demonstrating with the slogan “No More Reality” printed onto placards and banners. In many ways this request still informs our present. When facing today’s images, however, the request has lost its innocence.

Douglas Crimp, “Pictures,” October vol. 8 (Spring 1979): 75–88.