Everything is in motion in the main room of Rosa Barba’s exhibition at Parra & Romero, Madrid. The mechanical buzz of film projectors is broken by the tack-tack of a slowed-down typewriter and the purr of an engine that rhythmically bursts out. Dimly illuminated by their own light, four mobile sculptural works seem preoccupied by their own looping performances.

Rosa Barba’s work encompasses films, sculptural moving objects, filmic installations, and text pieces that are grounded in the materiality, functions, and structures of cinema. Like Georges Perec—from whom the title “Thoughts of Sorts” is borrowed—Barba is interested in inventing new ordering systems: different ways to classify the world in order to understand it on its own terms. Both disrupt conventional, established hierarchies. Perec produces literature as an ars combinatoria from surprising classifications and through list-making, while Barba dismembers and reconfigures the material and structural elements of classical cinema to produce conceptual mobile sculptures that are unexpectedly dense and engaging.

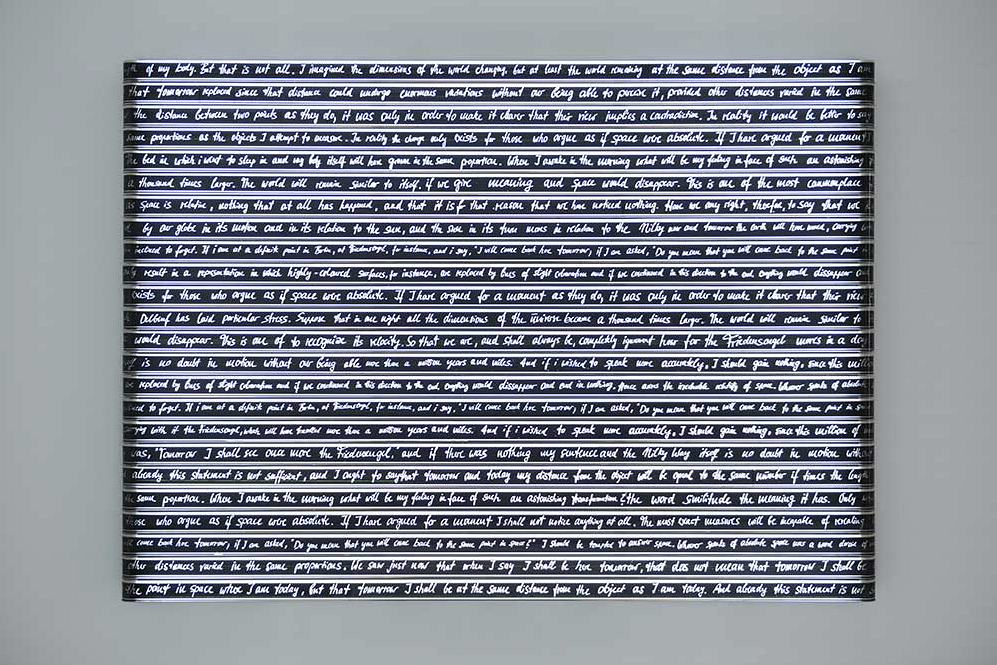

Spacelength Thought (2012)—an antique typewriter on top of a projector—types text onto 16mm white film. The slightly burned letters are projected one at a time onto the wall. While this “author” poetically extends the production time of each word on the wall, the printed film—on which the text could perhaps be read—piles up on the floor in a tangle. The old-fashioned projector in Focus Puller (2013) beams out a sentence, its focus alternating between the two glass screens that stand in front of it, constantly moving from one to the other in an effort to project a vivid image of the text. The sentence appears in focus for an instant, then blurred, as if this tireless attempt to focus were intended to evoke certain unstable or ephemeral thought processes. At the back of the room, sentences move at varying speeds across a screen made of horizontal lines of handwritten white text on black celluloid in Sight Enables Us to Appreciate Distance (2016). The pace is slow enough to keep us cross-reading, picking out words here and there, while the illuminated text slides along.

There is something hypnotic in these sophisticated, fragile mechanical sculptures. Doubtless it has to do with their performative nature and their power to recall behavior, as well as with their appearance of timelessness: they do not seem to belong to our time, but work here and now. But much of their power to seduce comes from the way they playfully fragment and disrupt meaning. Even if they have been amplified with a human capacity—language and its multiple transcriptions—the works alter categories and functions. Text is broken down, treated as image, or set in motion; writing is staged, but the text is unreadable, giving meaning an evanescent quality.

Rosa Barba is constantly reworking her pieces. Some works in the exhibition are the result of expanding her strategies and experience of site-specificity to indoor exhibition spaces. For her exhibition at the Centre international d’art et du paysage de l’île de Vassivière in France (“Is it a two-dimensional analogy or a metaphor?,” 2010), the artist placed a soundtrack in the lake, so that the acoustic waves were transmitted by the water and rippled its surface. Sat on the floor at the center of the main room at Parra & Romero, Conductor (2014)—a spherical object whose membrane is rhythmically deformed by sound—expands this investigation into the aural modulation of materials. The work has a more abstract presence than the surrounding mechanisms constructed out of projectors and celluloid, but like them it plays with the distance between subject and object.

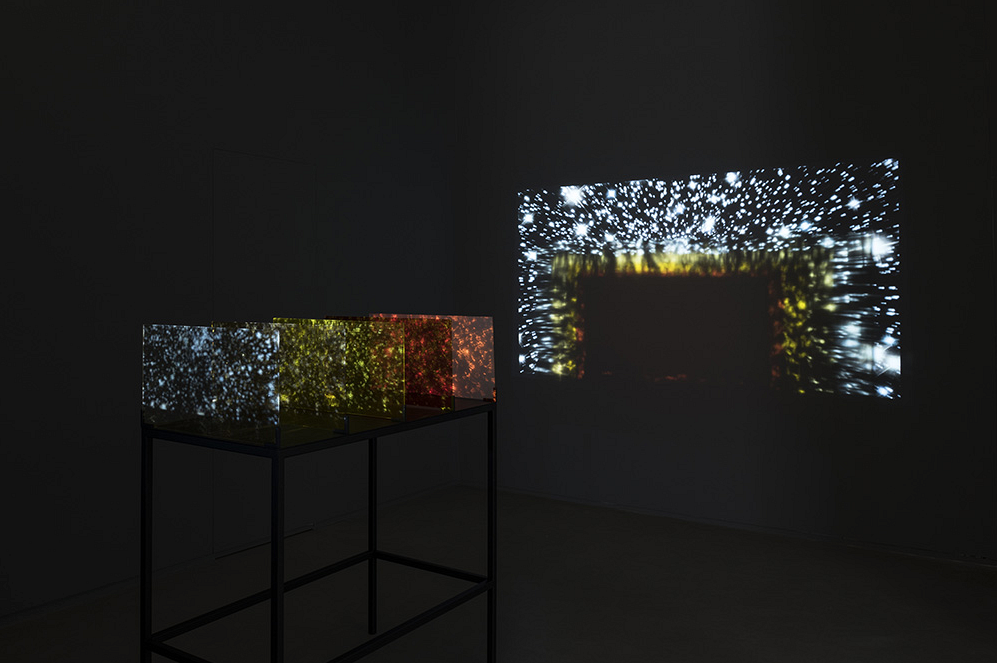

Showing in a separate room, The Color Out of Space (2015) is a maquette-sized version of her project at the Experimental Media and Performing Art Center, Troy, New York, during which she collaborated with the Hirsch Observatory at Rensselaer. In the original installation, Barba projected a film comprising images of planets and stars onto the building’s facade, creating an outdoor cinema. The film could be seen by anyone driving down the highway, while the soundtrack, which dealt with the speculative intersection of astronomy and art, could be heard on a local radio station.

The artist has transformed the piece into a delightful cabinet version, for which the film is projected through a series of colored glass panels that work like photographic filters. The color spectrum is a device by which we can read information reaching us from the universe, and color filters are also used in telescopes. The glass panels in the installation multiply and enhance the images while at the same time generating a shadow on the wall—a screen-shaped black hole surrounded by planets and stars. The work takes a reciprocal approach to astronomy and cinema, inquiring into the limits of vision and knowledge. Looking out into the terra incognita of the universe, we see images of things that may no longer exist.