One of the most affecting commissions of the 20th Biennale of Sydney is placed out on its own—“in between” its six main venues—at one end of the city’s Botanical Gardens. Archie Moore’s A Home Away From Home (Bennelong/Vera’s Hut) (2016) in part re-imagines the diminutive shelter offered to an Indigenous Australian collaborator in the white settlement of Sydney. It is a believable historical forgery, blending in with, and at the same time dwarfed by, the stately architecture of Government House. A quiet soundtrack of Aboriginal singing accompanied by clapsticks emanating from the otherwise apparently entirely European structure renders poignant its form, scale, and site.

If a white Australian expresses the opinion that immigrants should be sent back to where they came from, the appropriate retort is: “So, when are you leaving?” The unprecedented displacement of people today is Stephanie Rosenthal’s starting point for the biennale. Her post-Documenta 11 curatorial process has operated with an informant network of “attachés,” and her thematic elaboration presents the work through seven “Embassies.” Reclaiming the term, the embassies are imagined as “borderless” “safe places,” “transient homes for constellations of thought.” Yet, in a place where Indigenous Australians were not recognized as citizens until as recently as 1967, her curatorial fiat that the French-derived diplomatic words can be disassociated from colonial or imperial history does not wash.

Also “in between,” on the forecourt of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Richard Bell’s latest version of Embassy (2013—ongoing) goes some way towards redeeming the curatorial conceit. It pays tribute to the Australian Black Power movement’s watershed appropriation of the European concept, the original “tent embassy” erected in front of Parliament House in Canberra in 1972 (“Australia’s best ever performance art piece,” Bell quips at a screening and discussion hosted in his tent), instrumental in the recognition of land rights and the end of policies of assimilation. Visitors to the MCA’s Embassy of Translation are confronted with facsimiles of placards recorded in historical photographs: “White invaders you are living on stolen land,” “If you can’t let me live aboriginal, why preach democracy.”

Protest action became the chief legacy of the previous iteration of the biennale. An artists’ boycott was prompted by concerns over a founding sponsor’s income from contracts to supply the Australian government’s notorious offshore detention centers,1 one of the reasons for widespread international condemnation of the country’s immigration policy.2 Another fictional institution, Karen Mirza and Brad Butler’s “The Museum of Non-Participation” (2007–2016) makes a final presentation under that name as the sole occupants of the Embassy of Non-Participation at Artspace. Key works respond to civil unrest, whether in the Middle East or their native United Kingdom. A powerful two-channel video, The Unreliable Narrator (2014-15), explores the way the 2008 Mumbai attacks were shaped by a desire for media impact.

Mirza and Butler are amongst the artists Rosenthal carries forward from her “MIRRORCITY” (2014) exhibition at the Hayward Gallery, London (where she has worked for nearly a decade). The biennale shares that show’s interest in how the present both realizes and eludes historical conceptions of the future. Where “MIRRORCITY” referenced JG Ballard on the idea that science fiction’s traditional staple, imagining future technologies, is a spent task, her title for Sydney quotes William Gibson on the same idea: “The future is already here—it’s just not evenly distributed.”3 That the Pakistani militants who attacked the Taj Mahal Hotel in Mumbai used Google Earth, and satellite and cell phones—as explored by Mirza and Butler’s project— complicates any implication that access to technology directly parallels those inequalities of distribution that connect, say, to the refugee crises.

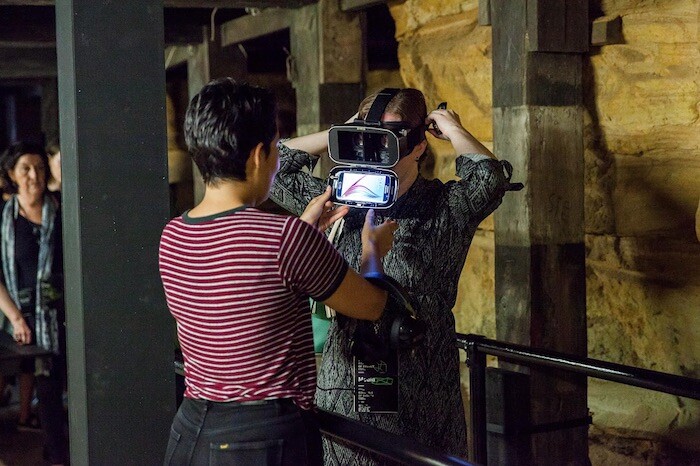

At the Embassy of the Real on Cockatoo Island, old media provide compelling figures of the saturation of our contemporary reality by information and imagery, in Maaike Schoorel’s subtle, barely figurative oils (as in Diver, 2015), that seem to find site-related imagery (indexed by a table of online research printouts) in the decaying walls of the rooms they were painted for, and Emma McNally’s large graphite drawings (the series “Choral Fields,” 2014-16) that create complex, brooding charts out of reference-less marks. Among the digital work, Cécile B. Evans’ witty faux-VR Preamble to a Prequel (of sorts), 2016, finds a somber rhyme in the actual VR headsets of A Walk in Fukushima (2016). The work allows visitors to the Embassy of Disappearance, at Carriageworks, to view the exhibition “Don’t Follow The Wind” (2015–) made within the Fukushima exclusion zone by the Japanese artistic collective Chim↑Pom.

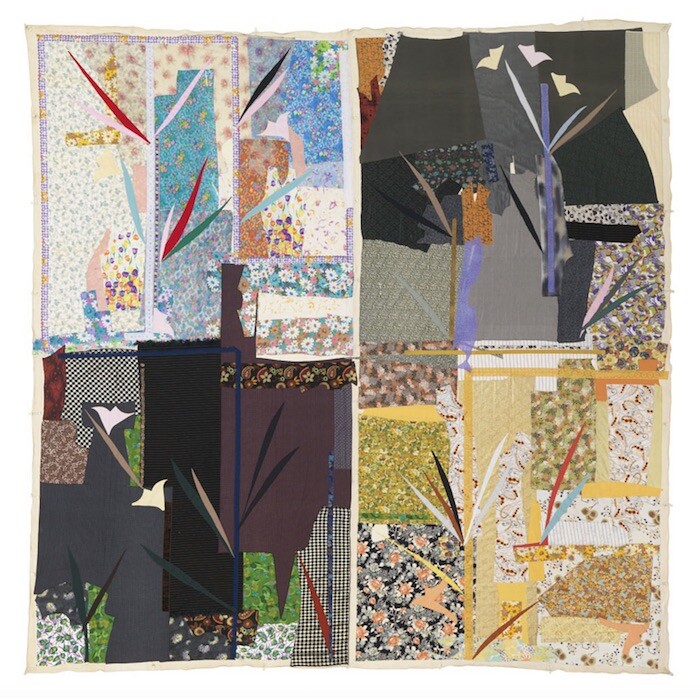

Rosenthal’s interest in dance and performance also shapes the show. Choreographer and artist Noa Eshkol is represented by her quilt-making (as well as samples of her movement notation), which, although shown at the Embassy of Translation, first came out of a principled withdrawal of her labor as a dancer. Boris Charmatz’s one-off performance manger (2014) offered spectacle on the one hand, while one-on-one live works—Germaine Kruip’s A Square, Spoken (2015), and Mette Edvardsen’s Time has fallen asleep in the afternoon sunshine (the latter curated in a small subsection of the show by André Lepecki)—added something less expected in this context.

Shahryar Nashat’s video Parade (2014)— which observes a full spectrum of movement, bringing the conditions of production (rehearsal) and commodification (marketing) into its frame—is a brilliant derivation from choreographer Adam Linder’s interpretation of Jean Cocteau’s Parade (1917), composed for Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes. His video shares with Camille Henrot’s bronzes (e.g. Retreat from Investment, 2015), Alexis Teplin’s Arch (The Politics of Fragmentation) (2016), and Justene Williams’ reworking of Futurist opera Victory Over The Sun, a fascination with an early twentieth-century European moment.

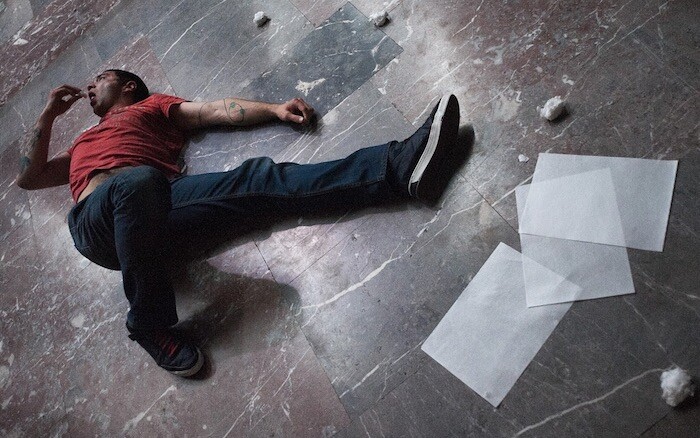

Linder’s own Choreographic Service No. 2, Some Proximity (2014) is also presented at the Embassy of Translation. Some of the best criticism that will be written on the Biennale is already here on the wall, in black marker on A4 sheets. Writer Holly Childs’s attention shifts from the works, to awkward phrases in the commentary, to what’s visible through the window, to the behavior of people viewing the work, in flashes of insight, enthusiasm (“I want to gram it!”) and irony. Two dancers’ tag-team, improvised readings of these sheets further estrange their jump cut syntax and bulks the material weight of words.

At either end of the exhibition, Samuel Beckett’s Film (1965) and Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s Home Movie (2016) are medium-reflexive meditations on the primal power, the horror, and the fascination of representations; a psychic depth to images affirmed by Charwei Tsai’s installation at the Embassy of Transition (composed of the works Spiral Incense Bardo and Scattered over the train tracks is A Dedication to Those Who Have Passed Through Mortuary Station, both 2016), which quotes warnings from the eighth-century Buddhist text Bardo Thodol that in the moment between death and rebirth it is important to recognize any vision that appears to us as a projection of our own mind.

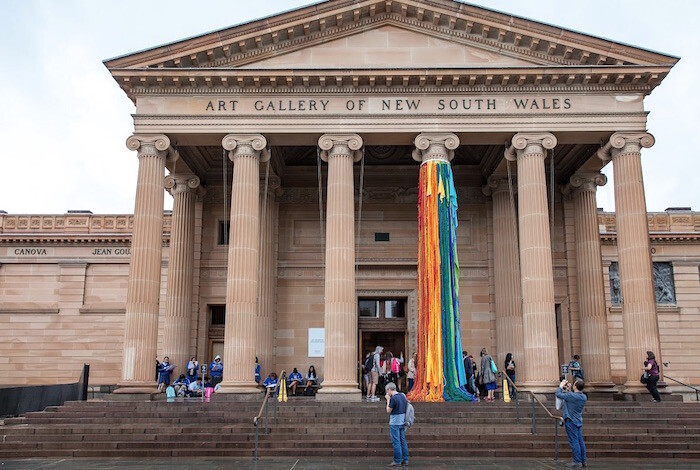

At the Embassy of Spirits, at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, other works enact pre-industrial concepts. Taro Shinoda’s beautiful chamber, Abstraction of Confusion (2016), offers a meditative space in which to be guided by “the voice of Ki” from Japanese tradition. Due to the sacred nature of the local knowledge Joyce Campbell’s anachronistic photographic process pictures, her collaboration with Richard Niania (Ngai Kohatu), Taniwha Whakaheke / Taniwha Descending (2016), was opened according to Maori tikanga or protocol in a public pōwhiri or welcome, which in turn required a formal Welcome to Country from a Gadigal Elder.

Contemporary technology simply but elegantly distributes its possibilities in the service of customary values in Yannick Dauby and Wan-Shuen Tsai’s video installation within the Embassy of Disappearance. One of the three works on view that concern minority populations in Taiwan, The Body of the Mountain (2015-16) is a document of the persistence of the “hunter lifestyle” of the aboriginal Atayul people. Its testimony to the relevance of older ways of living is one of many points at which the exhibition succeeds in suggesting ways past the ideas of progress that haunt its title. Like the “universals” of Western diplomacy, the question of how to reckon with the future (and the past) has a distinctive character in a settler colony like Australia.

See Danny Butt, “Transfield, Biennale of Sydney, and artistic complicity,” http://dannybutt.net/transfield-biennale-of-sydney-artistic-complicity/, posted February 24, 2014, and Victoria Lynn, “Art As Action” in Art As A Verb (Melbourne: Monash University Museum of Art, 2014).

See Amy Maguire, “Why does international condemnation on human rights mean so little to Australia?”, The Conversation, http://theconversation.com/why-does-international-condemnation-on-human-rights-mean-so-little-to-australia-53814, posted February 4, 2016, and “at work inside our detention centres: a guard’s story,” The Global Mail, http://tgm-archive.github.io/serco-story/.

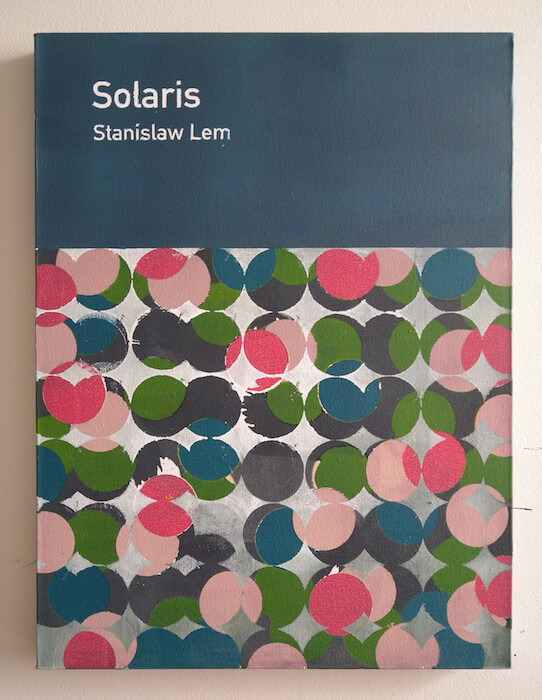

The Embassy of Stanisław Lem, not yet mentioned, presents the more-known-than-read (and, we learn, poorly translated) Polish science fiction author via a simple monument: an itinerant sale table of second-hand editions conceived by artist Heman Chong.