In November 2009, Isabelle Alfonsi and Cécilia Becanovic brought Marcelle Alix into the world. Located since then in the multiethnic neighborhood of Belleville, in the northeast of Paris, Marcelle Alix expresses its dual nature through its title, constituted by two French female forenames, Marcelle and Alix, neither of which corresponds to those of its founders. Bypassing conventional branding systems, proposing complex, often cryptic means of communication, and constantly engaging in forms of self-reflection, Marcelle Alix offers a rare example of what a gallery can be beyond its plain commercial vocation. In a four-person conversation, Isabelle Alfonsi and Cécilia Becanovic talk with Louise Hervé and Chloé Maillet—the artistic duo whose performance inaugurated the gallery almost six years ago—about the past, present, and future of Marcelle Alix.

Louise Hervé: When the four of us first met in 2008, Chloé and I had already been working as a duo for some years and had just finished a film, Un projet important [An Important Project], which relied heavily on collective work, with several performers and dancers. We were very touched by your own work as a duo. Later, when we started to get to know you better, we saw the duos Pauline Boudry and Renate Lorenz, Marie Cool Fabio Balducci in the gallery. Do you feel like saying something about duos?

Cécilia Becanovic: It’s easier to work as a pair. We’re stronger as a pair, because ideas circulate and because we make decisions without overdoing it, without veering too much towards one side or the other… It also gives us a unique flexibility and openness. We didn’t want a gallery that bore our two names. We wanted to create a third character and a program that relies on collective work and this interpersonal system; as [Witold] Gombrowicz said, “the other transforms us as we transform the other.” We were conscious of that, and we continue to benefit from it.

Isabelle Alfonsi: We’re not two, we’re three. Marcelle Alix isn’t the sum of our tastes, it’s how we built another taste, which is a bit of hers and a bit of mine but neither totally one nor the other, and as such independent.

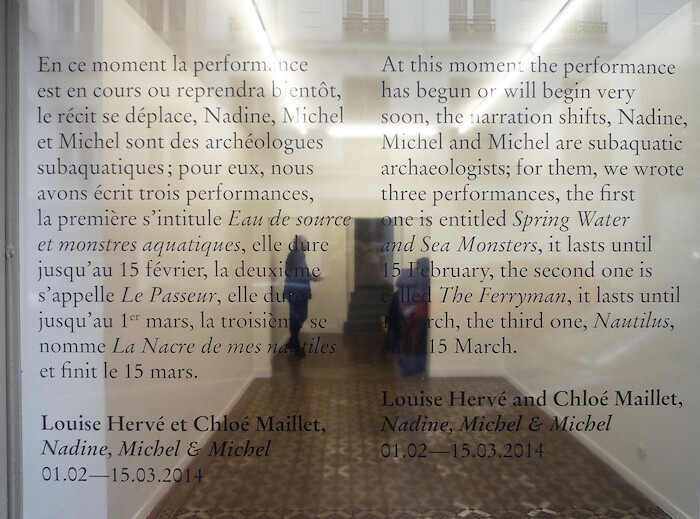

Chloé Maillet: It’s the same for us. What we do isn’t the sum of our tastes and interests; it’s something that happens in between the two of us! Marcelle and Alix are two first names, at the same time one and two persons. We really enjoyed that… In our first exhibition in the gallery, “La caverne du Dragon” [The Dragon’s Cave], in 2010, all the works had first names, and our second exhibition was called “Nadine, Michel et Michel.” We felt that this suggested a personal relationship, tinged with fiction, sentimental. In fact, I was thinking about Stendhal when I asked you this question.

CB: I totally agree with you. Ultimately, the fiction is an excuse. I believe that things are also being built in a very real, practical way. Marcelle Alix relied, from the beginning, on a horizontally structured team. We needed to play all the characters. When we met you, we were very pleased by this symmetry.

LH: It’s true that you hold something like a mirror to us; each time there’s a new show, it raises questions for us too. We also enjoy seeing you moving between the roles of gallerists, researchers, critics, curators, teachers… Do you have the impression of reinventing yourselves through this multi-tasking.

IA: It’s an intellectual need for us, and the gallery’s mission can only be enriched by it. We both feel the need to express our own voice elsewhere, through other collaborations. I am deeply engaged in feminism, which finds partial expression in the gallery but also elsewhere, notably in my research activities.

CB: I agree with Isabelle… I’ll be very sentimental… One day we decided to be as creative as possible, and now we realize that this took us far. People know our voices, they attest a certain intimacy, they are agitated, spirited, even slightly theatrical. Our texts aren’t simple assemblages of simple sentences, they create fictions with a certain weight over reality because they try to comprehend and pursue it.

IA: We also love lacking modesty (laughs). We love to live with it.

CM: I believe, Cécilia, that you once told us—don’t feel obliged to answer if you don’t recognize yourself in this quote (laughs)—that there are two kinds of artists: those who are able to remove themselves from their work to see it from the outside, who have a critical position in relation to it; and those who are totally inside it. Do you work differently with each of them?

CB: I love each of the artists we defend, but when I recognize this phenomenon, when the work and the person are unconsciously inseparable, I think that it moves me even more deeply than those artists who say very accurate things about their own work. I watch them evolve, I am pleased that they talk to me, but I feel they would do what they do regardless of me.

IA: Anything you say about such contained work, which has the artist at its core, will always be slightly false. So it’s better to take a personal approach, something very sentimental, vis-à-vis to their work. If you try to rationalize it using an intellectualized criticism written from the outside, you’ll destroy its beauty. When you talk about that, Cécilia, are you thinking of Marie Cool Fabio Balducci, and also of Ernesto Sartori?

CB: Or about Lola Gonzàlez. The way in which we love and present a work inherently transmits something. We must give back the trust that each person has in themselves, in their tastes: each person has a taste, we must exercise it. We have really done that.

CM: Marcelle Alix, the fictional character, has always made me think of Marcel Duchamp, of Duchamp’s feminine side, Rrose Selavy. Giovanna Zapperi maintains that it was only by being a woman that Duchamp could have been so modern. Is your feminism engaged with a concern for equality in a world and an art market that isn’t so? Or is it something else? Is Marcelle Alix post-queer?

IA: Our initial aim was not to right all the wrongs in the art world and market, but to say to all those who can’t find female artists that we can easily find 50 or even 60 percent, it’s no problem. Many women work in galleries: gallery assistants are mostly women, there are plenty of female gallerists, and then the exhibited artists are mostly men, which is strange, no?… But this issue interests me less from the perspective of a sexual male/female division than from a queer perspective, related to the affirmation of a minority perspective. What makes us queer and feminist is the affirmation that yes, we are vulnerable, we don’t control all the parameters, we make mistakes, but we embrace this situation and we turn what is perceived as a weakness into a strength. Galleries are meant to seem secure; even when they’re not, they should never confess to weakness. For me, the confession of weakness is essential to the gallery.

CB: The two words that I’d cling onto are, firstly, “kindness,” which is important because it’s not as simple as it appears. And also the term “vulnerability,” which I really like. With Marcelle Alix, we’ve grasped one thing after all these years: that we are the reflection of what art expresses. If in your daily life you assume a certain vulnerability as a human being, and if you create a work that recounts that vulnerability, without there being any crack between the two, it seems to me that something true might emerge. I really think this crystallizes our project.

CM: To conclude, we’d like to talk about time travel… The hill of Belleville has a political history. When you invited us to do a performance for the opening of the gallery in 2009, we talked about the Saint-Simoniens in Ménilmontant… And the underground station down the road will be renamed “Belleville - Commune de Paris 1871.” Is this significant for you? And I’ll ask you the final question straight away, as it will allow you to choose the moment in time at you’d like to situate yourselves… How do you imagine the outcome of the gallery? Charles Fourier said that we must test the phalanstery for 200 years before knowing what it would become… What is your timescale?

IA: I could say something optimistic yet not too engaging… (laughs). Even if one day the gallery stops existing physically, what we’ve created is sufficiently strong to continue to exist independently of the gallery. I feel that whatever happens to us or to the gallery, there is something that is likely to remain, somehow like the idea of the phalanstery…

CB: Optimism and faith are compulsory in this profession, as in all those professions for which one risks one’s own freedom. Not everyone is as invested as we are. When visiting exhibitions, people should formulate the same emotional attachments that they do with beings and things. For Marcelle Alix’s part, I hope we’ll continue to arouse affection and make it visible.

LH: Do you want to end with a love note?

CB: I’d like to conclude with a sentence by Guillaume Apollinaire, from his Letters to Lou, which I love to read back, especially in this period. He says: “The Martian era, these times of ours.”