The maxim “less is more” hardly springs to mind when thinking about Art Basel Hong Kong. Yet Art Basel’s global director, Marc Spiegler, uttered those very words during the media reception for this year’s edition, arguing for quality over quantity and noting that all three of the franchise’s fairs in Basel, Miami Beach, and Hong Kong have been shrinking steadily in terms of both exhibiting galleries and major installations. While the overall number of exhibitors at Hong Kong has diminished, the percentage with a permanent presence in the Asia-Pacific area has grown steadily: a little over half of this year’s participants have spaces in the region. This despite the turmoil in the Chinese economy, which—allied to the fact that this year’s auction sales have yet to match those in 2015—prompted some discussion at the media reception as to whether Art Basel expected reduced sales. Art Basel’s director for Asia Adeline Ooi was quick to point out that, as a regional commercial hub, Hong Kong attracts collectors from elsewhere than China.

All of the familiar Art Basel elements can be found throughout two halls of the Hong Kong Convention and Exhibition Centre, situated on the city’s bustling harbor. Encounters—Hong Kong’s answer to Basel’s Art Unlimited—is curated for a second time by Alexie Glass-Kantor, the director of Artspace, Sydney. Standout works include Indonesian artist Tintin Wulia’s installation Five Tonnes of Homes and Other Understories (2016), which brings Hong Kong’s hustling black market economy in recycled cardboard out from the streets—where it is used to package products, build temporary shelter for the huge Sunday gatherings of the city’s domestic workers, and as commodity in and of itself—and into the art market. If Wulia’s work helps to ground the fair in the city, Indigenous Australian artist Brook Andrew’s installation Building (Eating) Empire (2016) consists of blown-up archival photographs that challenge colonial histories of the region, which developed in parallel with the proliferation of photography. Indonesian collective Tromarama’s nearly 100 painted placards—Private Riots (2014-2016)—introduce a lexicon of pop imagery that refers back to the geopolitical struggles of the region and to issues of freedom of expression playing out in the country’s third largest city, Bandung (on March 23, a day prior to the opening of Art Basel Hong Kong, the French cultural center in Bandung and a local theater group canceled a performance under pressure from a nationalist group that accused it of promoting communist sympathies).

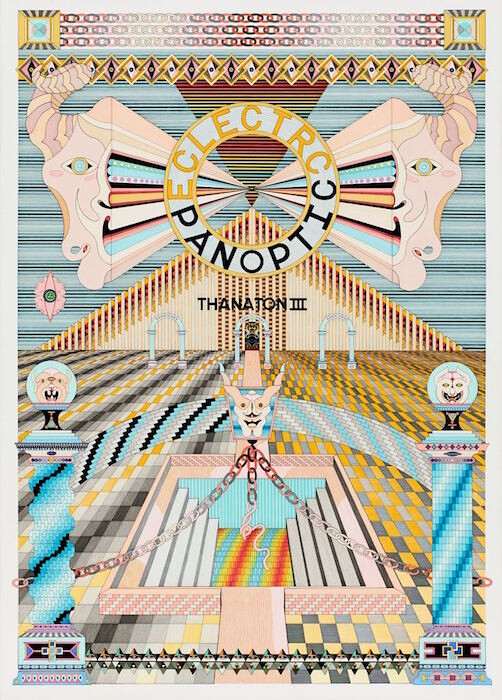

The Discoveries section focuses on single artists, enabling some intelligent presentations to stand out in a giant hall bursting with blue-chip galleries. Wu Tsang’s installation at Galerie Isabella Bortolozzi, Berlin, consists of a series of props and photographs alongside a bright red costume-like sculpture. They form part of the artist’s wide-ranging project Duilian (2016), inspired by the female revolutionary martyr Qiu Jin whose contested legacy is demonstrated by the 19 reburials of her body since her death in 1907. In a collateral project outside the fair, local arts organization Spring Workshop presents a film installation of the same project, centered on a newly commissioned film (also titled Duilian, 2016). Tsang’s films and installations combine numerous historical versions of Qiu Jin’s unstable story with the artist’s own invented narratives. Further compelling feminist visions can be found in Mira Dancy’s paintings at Night Gallery—among them Don’t Bury Me and Blue Exile (both 2016), depicting nude women who seem utterly indifferent to the male gaze—and in Jess Johnson’s technicolor installation, a psychedelic alternate universe, at Darren Knight Gallery. With works such as Eclectrc Panoptic and Platform Masters (both 2015) the artist stakes a claim to the male-dominated realm of science fiction and gaming.

Participants in the Galleries section are at liberty to present a broader spectrum of their stable of artists, but those who opted for focused selections of one or two artists stand out. Greene Naftali, New York, is showing a pared-down selection of Paul Chan works, including Triosophia (2015), a circle of three anthropomorphic nylon figures seeming to hold hands and dance as their forms are filled with air from fans, like the awkward inflatable dancers used as curbside advertisements. These focused exhibitions offer reprieve from the art overload that is typical of fairs, but the fact that the vast majority of veteran galleries—Gagosian, Lisson, and Marian Goodman among them—opt to present a wide array of their artists’ work suggests that this more popular model is better for business.

Lending depth to the fair, Art Basel Hong Kong’s Conversation series and Salon program bring together an impressive list of artists, curators, critics, and gallerists—such as Simon Denny, Heman Chong, Cosmin Costinas, Hans Ulrich Obrist, Su Wei, and Chang Tsong-zung—to discuss timely topics including “Collecting as a Radical Practice” and “Funding and its Discontents.” In combination with the film program—curated for the third year by Li Zhenhua, who has developed six thematic streams including “When History became Emotion” and “Becoming an Artist”—the fair serves as a pop up contemporary art institution in a city still waiting for its mammoth museum, M+, to materialize. “Less is more” was hardly the guiding principle for the discursive program.

As Art Basel Hong Kong has cemented its position as the premier art fair in Asia over the four years since its debut, so the independent and non-profit sector in the city has also seen a period of growth and development. Para Site, Hong Kong’s longest-running independent art space, relocated to a larger, refurbished location on Quarry Bay in early 2015. The current exhibition, “Afterwork,” is a sprawling group show across six rooms that tackles issues of labor, class, race, and migration as they relate to Hong Kong. The migrant workforce has underpinned the territory’s economic success for centuries, and this exhibition developed out of a number of long-term collaborations between Para Site and local workers. The revelation of racial and social divides in the photographs of Xyza Cruz Bacani and the critique of official and popular opinion by Filipino domestic workers in the satirical comic strips of Larry Feign, among others, serve as a poignant counterbalance to the impermanence, unfettered commerce, and frenetic energy of the fair.