“Rats live on no evil star.” And “In a regal age ran I.” There is no apparent truth, no evident foundation, in these two double-sided expressions—same characters, reverse order—whose heads and tails can switch places like a juggler’s pins. Just a tumbling act of letters on the tightrope of some semblance of meaning, found in those special words or phrases that can be read from left to right or right to left without a hitch, through a simple mechanism properly termed a palindrome—from the Greek palindromos, “running back again,” like a crab, after it runs forward.

Montreal-born, London-based Allison Katz is a true virtuoso of the genre, to the point that she’s titled her first exhibition with Giò Marconi in Milan “AKA”—a palindromic acronym that naturally stands for “also known as,” but which takes on a broader scope here with its almost obligatory hint at the initials “Allison-Katz-Allison.” Linguistic and phonetic associations do seem to whet the appetite of this Canadian artist, who also played with the sound of her first name in the title of her most recent solo show at Kunstverein Freiburg, “All Is On” (All-is-on), to which the show at Giò Marconi acts as a sort of postscript, an afterword. In Katz’s words, a “rider, tailpiece, coda.”

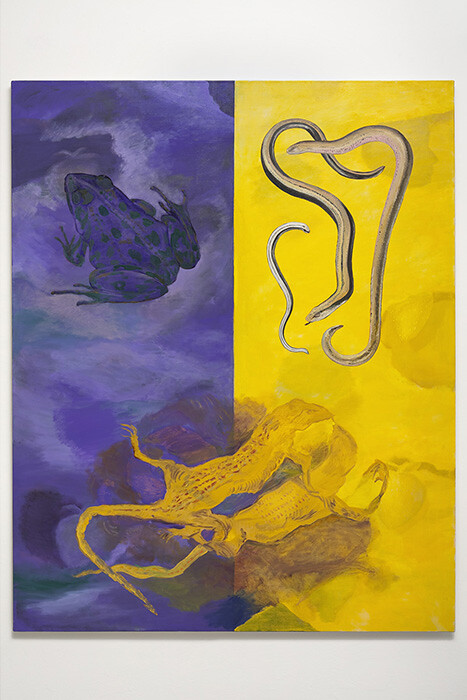

This piercingly calm exhibition features a selection of ten paintings, as well as six posters that hang in the entryway like a sort of musical overture, presenting a suite of blunt, raw scenes that range different rhythms and moods. Each stands alone, nursing its own testimony. A pale blue dog, with drooping ears and tail, turns its back on us (Anyone with the wish, 2015); a cosmic egg, resting solidly on the void, flaunts its white rotundity (I, 2015); a mask with empty sockets shows us its grimace (Marienbad Fountain Off, 2016); a humpy frog, a clutch of snakes and a pair of geckos are crouched, clustered, and stretched out in an enigmatic triangulation, like a rebus (Guts, 2016). The paint (oil or acrylic) is applied in a perfunctory fashion, without giving the subjects a finished, conclusive body, without explaining the whole underlying game. We get a keen sense of something hermetic, moody, and human. Not all the allusions can be fathomed. Some can only be glimpsed, whiffed. Others remain ungraspable, in gridlock.

Through a series of sudden expansions and contractions, concealments and revelations (orchestrated by the angular flats or partitions that the artist has slipped into the otherwise rectangular vessel of the gallery), the show unfolds from one end of the exhibition space to the other without the constraint of a single direction or orientation—we move indiscriminately from “A” to “K” and “K” to “A.” The right glove fits perfectly over the left hand. The tempo is set by a permeable to-and-fro between “inside” and “outside.” Here the casual trompe-l’oeil of a knob lets you identify an oil as a small door. Over there a large painting shows a car through the window of another vehicle (or maybe it’s the same car seen from inside and outside?) A similarly twinned gaze is found, right at the entrance, in Double Hunger (2015), the painting of a devouring creature (a mandrill or macaque, judging by the sparse tufts of fur): all compressed within the round funnel of its mouth, we observe—as savaged victims, but still ourselves—another monkey gobble down its lunch. Like orifices, mouths, sphincters, these scenes seem to go beyond the exhibition walls, and one is led to wonder what they hide in their depths.

“The whole exhibition has the form of some organism,” the young gallery assistant explains in response to my question about the origin of some titles—like Brain (2016, the little door divided into two “hemispheres”); Guts (2016, the tangle of reptiles and amphibians); Beating Heart (2016, the car window)—all the while, rotating in her right hand, one of Katz’s pear-shaped glazed ceramic pieces, Arsi-Versi (2014): nose on one side, butt on the other. This annotation charges the works with an unexpected visceral quality and with nuances that sometimes seem sanguine, sometimes more bilious. “Now, see, all the warm colors are visible along a diagonal,” the assistant continues, guiding me to the entrance and directing my gaze to the paintings in view (predominantly red, yellow, orange) that the partitions jutting out along that line cannot hide. “And from here”—in a few bounds she’s already on the other side of the room, shouting as she points to other realms (the reverse of what I’m seeing) that remain out of sight to me, “there’s a prevalence of cool colors: blues, grays, purples.” We switch places—one moving up, the other down—as if pushed by the opposite currents, red and blue (as anatomy textbooks depict them) of arteries and veins in an imaginary cardiovascular system. All around us, the exhibition aligns and arrays itself in one sense or the other, without losing its meaning or syntax. Like a palindromic word.