Siera Hyte’s “The Sometimes Hour”—an installation of carefully corroded objects and scratched or tampered images at Ellis King gallery, Dublin—has the air of a murder mystery. Hyte’s is one of two solo exhibitions running simultaneously in the space, the other a retrospective of the American artist Michael Ross, whose confounding matchbox-sized reliefs made from found armatures, plastics, screws, fabrics, and other seemingly symbolic material hang, evenly paced, on the wall. It is difficult to see a formal connection between the two artists, but the slow, up-close scrutiny commanded by Ross’s tiny intrigues carries over into a close inspection of each of Hyte’s component works.

Hyte’s bright, airy space is set up like a film set or crime scene. Objects perch on shelves (Fear of a stranger II, all works 2016) or sit on the floor, with other two-dimensional elements hanging framed, plastered, or pinned to the wall. The objects include vintage perfume bottles, each one a different color and pattern of cut glass, some with atomizers bound in diversely colored tassels. This dispersed collection would seem glamorous to the point of kitsch were it not for their curious surface covering of salt flakes. Hyte has distilled salt water so that its saline residue encrusts the surface, and the effect to the viewer-cum-detective zigzagging between clues is that they have been rescued, jewel-like, from some body of water and presented to us as evidence. Nearby, a brass coal box sits on the floor, its antique sides and lid embossed with the picture of a man on a shoot, rifle poised and gun dogs at the ready. Its surface has been dezincified, again by salt water, so that the margins of the hunter’s image are stained with turquoise corrosion. This work’s title—With all my heart, I still love the man who killed me!—suggests foul play.

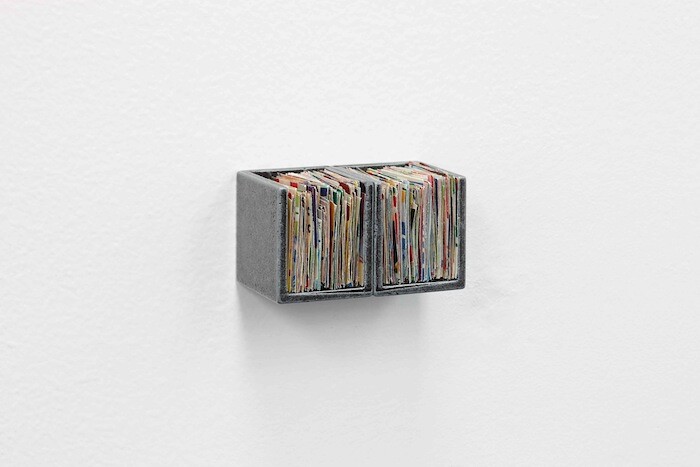

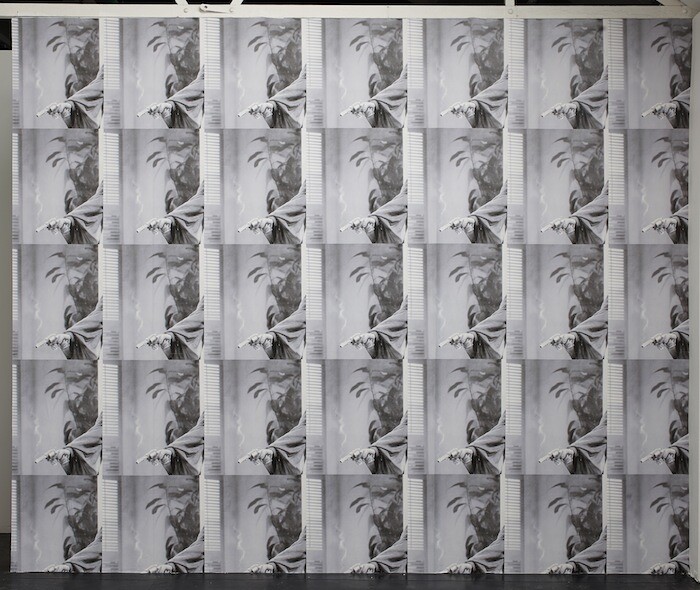

Hyte’s degraded images are inflected with new meaning. Two of the walls are papered with identical images, cropped and repeated in a large grid effect, titled With all my heart, I still love the man I killed! On one wall the repeated image is of a woman standing behind a banister, covered by sackcloth. She’s sneaking in. On the far wall, the repeated image is of a woman’s hand holding a pistol, her arm extended towards a target on the floor, about to pull the trigger. The serial images read like a film reel pausing on (by repeating) one image to build tension—the key moments of the crime. Four more “drawings” pinned to the wall are constituted from used US lottery scratch cards, each branded with their own logo and icon, such as “Love to Win” (covered in pink and purple love hearts) and “Double Shot” (with a backdrop of two cups of coffee). Alone, they’re paltry works but they complement the whole and within this skittish, noirish exhibition they brim with innuendo.

The actresses construct a trap I, II, II and IV are four inkjet prints on envelopes showing color stock images of attractive young women in benign poses, their images cropped to fit into the “smart art” familiar from Microsoft PowerPoint: arrows, boxes, and ovals. Beneath each one, the sentence, “Robert will be away for the night. I must see you. I am desperate… Don’t drive up.” Advertising’s click-bait (the “nice girl” stock image) teamed with the schmaltzy iconography of corporate presentations, and peppered with a seedy bait note, makes for the strongest work in the exhibition.

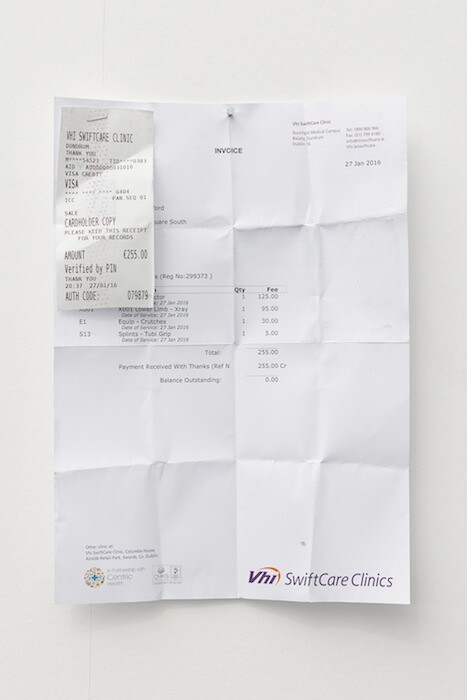

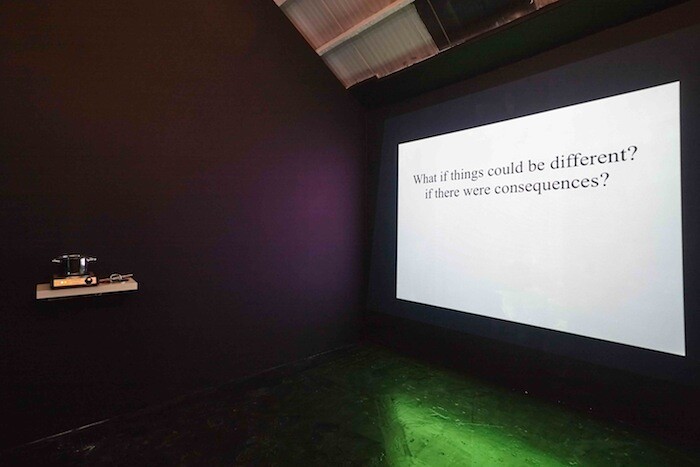

The bait note summons Robert Durst, the American real estate heir who allegedly killed his wife before disposing of her body in the lake beside their country house in upstate New York in 1982. The story resurfaced last year through a high-profile and insidious documentary by Andrew Jarecki. Is this Hyte’s take on things, from the perspective of Durst’s washed-up wife, who comes back to kill him? Hyte’s central narrative, of course, could come from this or many other found mysteries, or even, no specific one at all. One projected text piece, Revenge Fantasy, clarifies that “this is a meditation on a world where victims could come back and haunt their aggressors.”

Less effective is Martin’s Fall, for which the scuff marks of a technician’s accident during install is marketed as work. It’s a rushed and ill-considered contribution to an exhibition that is otherwise precariously cohesive, an unwelcome diversion from this odd, loose narrative of two gun-toting lovers. Casting that work aside, I was reminded of tracing clues, corrosions, and captions around solo exhibitions by Sam Anderson, Trisha Donnelly, and Lutz Bacher (alongside whom Hyte recently exhibited in the group show “Friday, 31 July, 2015” at Essex Street, New York), postscripts to what Ralph Rugoff labeled the “forensic aesthetic” of the late 1990s, “an approach in which the artwork is presented as the residue or record of an earlier event, sometimes to an extent where distinctions between sculpture and performance seemed to blur.”1 What distinguishes Hyte’s clue-trail is her capacity for refitting images within a scheme that provides moments of whimsy as well as deep distrust and welcome criticality.

Ralph Rugoff, “Scene of the Crime,” a talk delivered at the Kunst-Werke Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin, on June 2015. The talk expanded on the theme of an exhibition of the same name that he curated at the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, in 1997.