Munem Wasif’s serene photographs, which are among the first works you encounter at the Dhaka Art Summit, depict one apparently desolate landscape after another. But if you stay with the images—don’t follow the urge to move on—then small figures start to appear. In one, which seems initially to document nothing but a barren landscape of rocks, gravel, and a pool of water, a bathing man becomes visible. A head, hands, kneecaps break gently through the surface of the water, and of our first impressions.

The space around the man opens up, nature unfolds into culture, and landscape becomes a background for imagined narratives about the man taking a dip in the pond. The presence of the body converts a beautiful landscape into a space for imagining the past and the future. Is he a farmer who has left his cows on the riverbank? Or a poet, perhaps, thinking of Narcissus, gazing at his own image in the watery reflections?

Art spaces are thoroughly scripted. We move through them by (often unconsciously) following instructions, and direct our attention according to narratives about what is worth seeing and not, decisions taken in our heads and expressed with our feet. But there are always glitches in the software, ghosts in the machine, which invite us to read (or write) another story. Wasif’s small-scale, black-and-white photographs—and video installation Land of the Unidentified Territory, 2015—haunted me throughout the Dhaka Art Summit because they captured a relation between invisibility and visibility that mirrors the exclusion of local poverty from the Shilpakala Art Academy, which hosted the entire summit.

Bangladesh is one of the poorest countries in the world. It was estimated in 2010 that about 70 percent of Dhaka’s households earn less than 170 US dollars per month, and 1 in 4 adults are unemployed.1 Poverty is everywhere outside the summit. Not just in the children looking for food in the garbage on the street, to name one of the scenes I witnessed, but in the state of the buildings and roads which makes it impossible for an ambulance or a police car to move swiftly through the city. Should this be addressed more directly? I’m not sure. The summit brings benefits, among them the possibility of thinking about the city in terms other than its poverty. On the other hand the distance between the art-consuming elite and local people is more striking here than at other comparable events across the world. There are no stable scripts available for bridging this divide. But there are alternative readings. Perhaps Wasif’s photograph, and the fact that we have to spend time with the image to see its hidden figure and the subsequent transformation of the landscape surrounding him, provides one model.

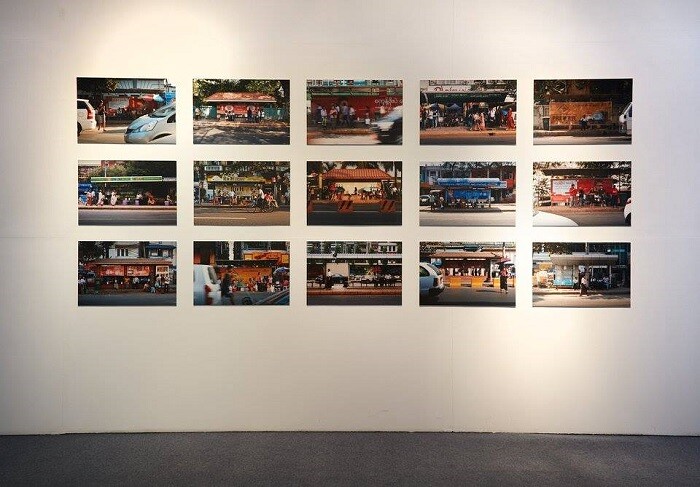

In VIP Project (Dhaka) (2014-15)—the latest in a series of “VIP Projects” by the Myanmar artist Po Po—this relation becomes a question of class. By putting up a VIP sign on bus stops around the city, he shows us how rarely most people challenge stories about privilege. Locals respectfully avoid the spaces defined by the signs. The project, which is documented thorough a film and a group of photographs, ironically connects with the summit itself: next to it, a guard blocks anyone without a VIP-card from entering the area reserved for international press and museum-workers from around the world.

At the Critical Writing Ensemble—which “seeks to foster a community of art writing peers working together”— Quinn Latimer inserted a rhythm into the summit by reciting her poem “Corpse Life”: “Corpse that keeps you company / Like a woman, / Through the billable month / Like a woman, / Each of your non-native / Like a woman,” she chants. The reading, punctuated by encouragement, reverberates throughout the art spaces and tells us that systemically anchored power—as exposed in VIP signs or the scripts by which we experience art—can be replaced by a different cadence. Through the beat of singing, talking, and writing (for instance), we can share spaces differently.

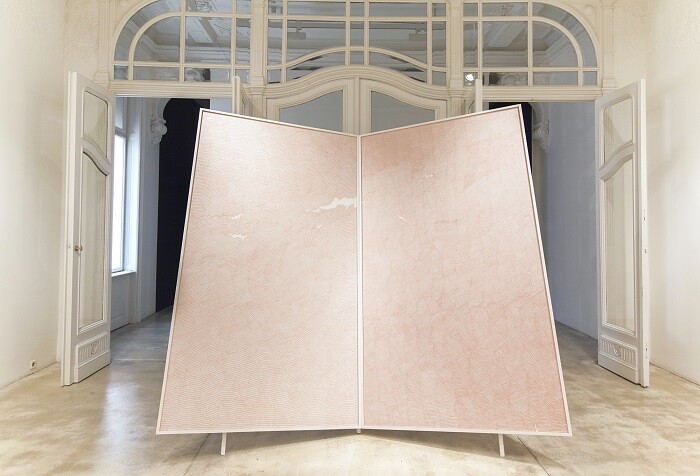

Latimer’s invocation resonates with several works, among them Shakuntala Kulkarni’s four-channel video work Julus (2015), in which a woman dressed in combat gear multiplies into an army of herself in a monochrome, theatrical space. The way she translates different kinds of armor traditionally worn by men—Vikings, samurais—into a skeletal combat-hybrid is stylized and effective. The shallowness of male poses are re-exposed as an image of female power; the armor is not for fighting but for redefining how we think about stereotypes. Like a woman, indeed. Latimer’s poem also corresponds with those works addressing meditation and ritual, of which Waqas Khan’s In the Name of God (2015) is perhaps the strongest. With its gigantic lined pages laid to rest like an open book, it brings to mind hours spent in contemplative study of a religious text. Khan is working with Sufi scripts, but we might as well think of the Bible or the Quran.

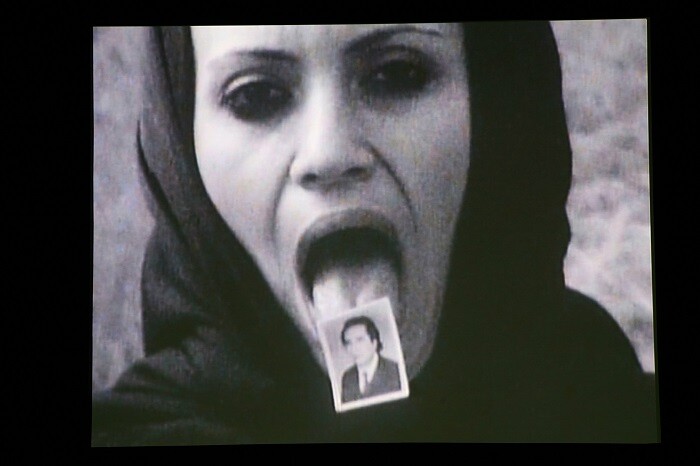

The summit’s film programme oscillates poetically between the past and the future—what you can and can’t see. The combination of older and new films works well as a series of thoughtful and slightly melancholy meditations on the question of memory, and in what sense we can still connect with the past. The programme, delicately put together by Shanay Jhaveri (Assistant Curator of South Asian Art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art), alternates between textured narratives of form and rhythm, abstracted in their flickering pulse, and fragmentary streaks of bygone times. Soon-Mi Yoo’s Dangerous Supplement (2005) is a film collage of US military footage from the Korean War, but there is little destruction or violence. We are not provided with an objective account of what happened, but rather with fragments of what US soldiers saw: a group of children dancing, trees blowing in the wind. The subjective point of view is even more pronounced in Kohei Ando’s My Collections (1988), which organizes the world into personal archives of everyday objects, or in Ben Rivers’ mysterious Things (2014). The films highlight how the idiosyncratic, the counter-script, might bring us closer to the intimacy of past experience.

Tino Sehgal’s Ann Lee (2011)—his interpretation of the collaborative project inaugurated by Philippe Parreno and Pierre Huyghe which takes a manga character as its central subject—challenges the implicit assumptions in these scripts by refusing to document them. Ann Lee is here played by a young girl, a two-dimensional character become flesh. Sehgal reminds us of how art can give life to something left dead by repetition or automatization. She smiles, looks at me, expresses emotions more complex than any script can contain. This undocumented space, this engagement with Ann Lee, is precisely here, in the landscape of Shilpakala Art Academy, in the coordinates of Dhaka Art Summit. She is a figure in a landscape onto whom we project our imagination.

Curator Chus Martinez grabbed my attention with her ideas about art as an extension of the body—an organ. She recalled a previous conversation with Raphael Montañez Ortiz, the founder of El Museo del Barrio (where Martinez previously worked as Chief Curator), who had suggested that every exhibition should start as a rainforest. She didn’t understand the idea at the time, but it stayed with her. Rainforests are vast—hyperobjects rather than ready-mades, impossible to grasp in the mind, let alone fit into an art space. Instead of thinking of this as a map of the impossible, Martinez suggests, we might consider it as a situation in which the distinction between art and not-art breaks down. Now, art becomes an organ because it is a way of maintaining paradox as a category of experience rather than a problem that should be resolved.

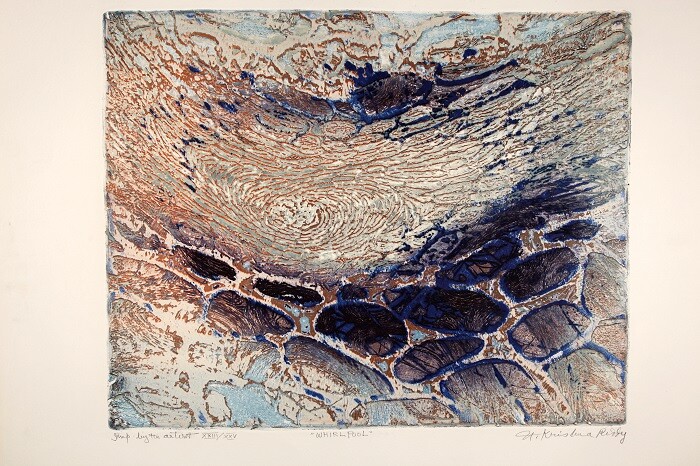

By the same reasoning, art also allows us to address the immensity of history. In Memento Mori (2016), Indian photojournalist Pablo Bartholomew shows us portraits of impoverished Bangladeshis taken as part of a 1986 National Geographic assignment in the country. The rolls of film, improperly stored, have been destroyed by termites: there is little of the original images to be seen, but the ruins of them force us imagine what is not there. Both Mustafa Zaman’s series “Lost Memory Eternalised” (2015) and Dayanita Singh’s Museum of Chance (2014) display personal archives of images in which the story connecting the scenes and people is lost. They still work as coordinates for mapping the relation between then and now, though. By spending time with the fragments of the past, the gap between the real and the imagined can be closed. Art spaces are scripted spaces, but it is possible to construct counter-scripts. Details can transform the whole, if we are attentive to them.

http://www.cbsnews.com/news/dhaka-bangladesh-fastest-growing-city-in-the-world/