In recent months, two film works from 1976 made their belated débuts on the art market, retroactively issued in limited editions. Last June, London’s Thomas Dane Gallery showed the meticulous restoration of Bruce Conner’s Crossroads, while in September, New York’s Greene Naftali exhibited Paul Sharits’s Dream Displacement, also recently restored. Crossroads was notably unaccompanied, departing from the common tendency—exemplified by the Sharits exhibition—of presenting films alongside works by the artist in other, more traditional media. This latter practice has a double function: it contextualizes moving-image works as part of a broader practice rooted firmly in the domain of art (rather than that of cinema), while also more pragmatically situating the film as a loss leader that might be less likely to sell, but which will direct interest towards items that are more readily collectible, such as drawings or prints. Nevertheless, in both of these exhibitions a significant metamorphosis was occurring: after possessing no real financial value on the art market for decades, Conner and Sharits’s films were posthumously entering a new economy. Following the success of Crossroads, further films by Conner will be restored and editioned; Dream Displacement is the second work of Sharits’s to receive this treatment, after Shutter Interface (1975) in 2009.

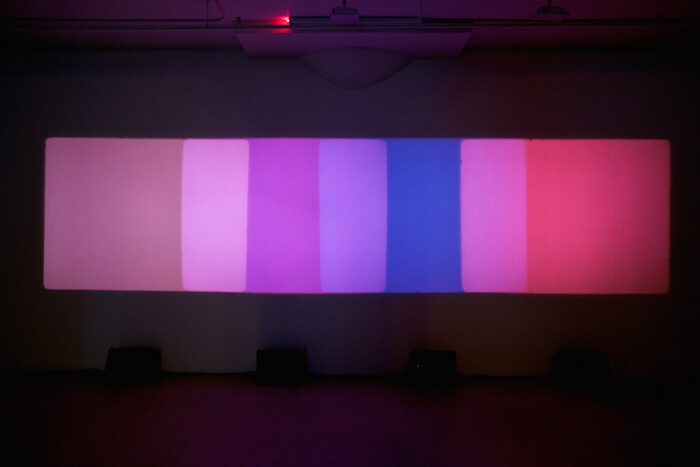

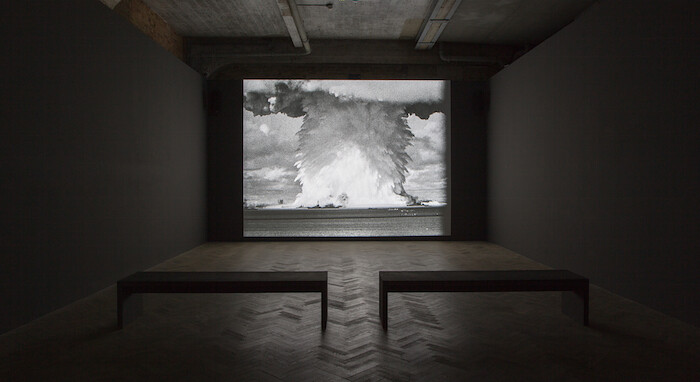

In Sharits’s case, this shift has meant a new visibility for his “locationals,” the artist’s name for multi-projection installations like Dream Displacement and Shutter Interface, until recently much less known than single-screen films such as Ray Gun Virus (1966) and T.O.U.C.H.I.N.G. (1968). With its multiple-projection apparatus and non-teleological structure, Dream Displacement was originally intended for a gallery setting. Crossroads, by contrast, was not only entering a new economy but also a new exhibition space. This compilation of appropriated footage of nuclear tests at Bikini Atoll in 1946, accompanied by a haunting soundtrack by Patrick Gleeson and Terry Riley, lived much of its life in the movie theater—until Conner reconceived it as a digital installation for “Unknown Quantity,” an exhibition curated by theorist Paul Virilio for the Fondation Cartier in Paris in 2002–3. A presentation at the 4th Berlin Biennale (2006) followed. What had been an intense 36-minute confrontation with what art historian Johanna Gosse terms the “atomic sublime” is now a loop one can walk in and out of. It must be noted that the costly restoration of Crossroads depended on its entry into the art market, and that its presentation at Thomas Dane was absolutely pristine.1 Nevertheless, leaving the economy of experimental film means leaving its exhibition context, despite the latter’s provision of a superior experience for the viewer.

The presence of figures such as Conner and Sharits on the commercial gallery circuit—a status that eluded them in their lifetime, during which they were primarily recognized as filmmakers—demands to be seen as the apotheosis of a development that has now been underway for some 20 years: the recuperation of the history of experimental cinema into the art context. While the two have long been marked by significant points of interconnection, they have equally been characterized, at least historically, by very different disciplinary, economic, and institutional formations. But today, with Jack Smith’s estate represented by Barbara Gladstone Gallery and Kenneth Anger offering a three-screen reconstruction of Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome (1958/2014) through Sprüth Magers in the Unlimited section of last year’s Art Basel—to say nothing of the recent presentations of Stan VanDerBeek at Andrea Rosen in New York or Malcolm Le Grice at Richard Saltoun in London—it is increasingly evident that a major transformation has taken place.

Anger, Conner, and Sharits were included in the 1996 exhibition “Art and Film Since 1945: Hall of Mirrors.” Curated by Kerry Brougher for the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, the exhibition’s reading of film history was representative of its time: an engagement with the populism of classical Hollywood (especially Hitchcock) and the modernism of European art house was positioned alongside the formal innovation and reflexivity of major figures from the experimental film tradition so as to offer a prehistory of the gallery-based practices then emerging. Not all in the film world were pleased with this migration of cinema: Alexander Horwath, head of the Austrian Film Museum, wrote in 2008 that the popularity of cinema-themed art exhibitions (then at its height) existed in “an inverse relation to the number of successful presentation models we see,” while many remarked upon the difficulties of format-shifting, excerpting, and distracted spectatorship.2 Nevertheless, such curatorial gestures, increasingly prevalent in the years that followed, paved the way for the recent market valorization of historical experimental film.

While interest in this tradition continues, the contemporary moment suggests that the time has come to mine another corner of film history. References to Hollywood have faded, giving way to an increased focus on the essayistic, political cinema of docu-fiction hybrids, particularly work from the 1960s and 1970s. As was the case with the 1990s’ dive into film history, this excavation can be said to occur once more in an effort to propose precursors for the practices of today, while feeding curatorial neomania with unprecedented presentations of figures tremendously accomplished yet perhaps relatively unfamiliar to an art audience, stemming as they do from the world of cinema. In 2014, Whitechapel Gallery in London mounted the solo exhibition “Chris Marker: A Grin Without a Cat,” co-curated by Christine van Assche and Chris Darke. It was touted as the artist’s “first UK retrospective,” notwithstanding a two-week retrospective held in the ICA in 2002, albeit in the cinema. Marker was also included in Okwui Enwezor’s “All the World’s Futures” at last year’s Venice Biennale, where he was joined by Harun Farocki and Alexander Kluge. On December 3, 2015, the group exhibition “The Inoperative Community” opened at Raven Row in London, featuring over 50 hours of work by filmmakers such as Jean-Pierre Gorin, Marc Karlin, and Jackie Raynal, set into conversation with recent practitioners like Eric Baudelaire and Mati Diop, who explicitly engage with the radical filmmaking of the 1960s and 1970s. As curator Dan Kidner puts it in his introductory essay, the exhibition concentrates on the legacy of films made during the “long 1970s” (1968–84) that manifest a strong investment in narrative—whether the essay, the diary, or the documentary—“to address ideas of community and the shifting nature of social relations.”

Forays such as these into this rich area of practice are certainly welcome, as they possess the ability to expose this material to new audiences, underline its aesthetic and political relevance for our contemporary moment of crisis, and build on the ways in which many of its central figures occupied interstitial positions between film and art. And yet despite the fact that we are arguably witnessing a second wave of infatuation with film history, it is not always clear that significant progress has been made in resolving the issues that emerged in the 1990s regarding how best to transpose films made for theatrical exhibition into the gallery context. Indeed, there is unsettling evidence that the situation may have worsened—particularly given that many works of the experimental documentary tradition tend to be at least feature-length and, owing to their engagement with narrative, resolutely dependent on start-to-finish viewing.

At Whitechapel, a brief excerpt of Marker’s essay film Sans soleil (1983) was displayed on an enormous translucent screen with muddled sound, while the 240-minute A Grin Without a Cat (1977) was projected in an open, insufficiently dimmed space with a few bean-bags littered in front of the screen—a perfect place for weary visitors to sit and check their glowing smartphones. Given that Marker produced a wealth of installation-based work and amassed an enormous trove of ancillary documents that could easily fill an exhibition, why show these films in the gallery at all if the viewer’s encounter with them was so impoverished? At Venice, Kluge’s nine-hour documentary News from Ideological Antiquity: Marx/Eisenstein/Capital (2008–15) was presented as a cramped three-channel installation that made attentive viewing impossible. Farocki fared worse: his entire oeuvre was displayed simultaneously and silently on laptop-sized screens in a gridded “Atlas”—enough to make Aby Warburg turn in his grave—while a single, rotating film played with bad sound in a small adjacent room. In Artforum, Jessica Morgan tried to recuperate the “negation of presence” she discerned throughout “All the World’s Futures” as “a critical reflection on the conditions for presenting art,”3 but it appeared rather that the exhibition was intent on reproducing at the level of display precisely what it decried at the level of content: a capitalist economy of subsumption, disposability, and distraction. In this sense, its installation design was truly a reflection, but one that was far from critical. Farocki and Kluge’s inclusion seemed more geared to listing their names on an exhibition checklist as evidence of curatorial savvy than to offering any sustained experience of their formidable works.

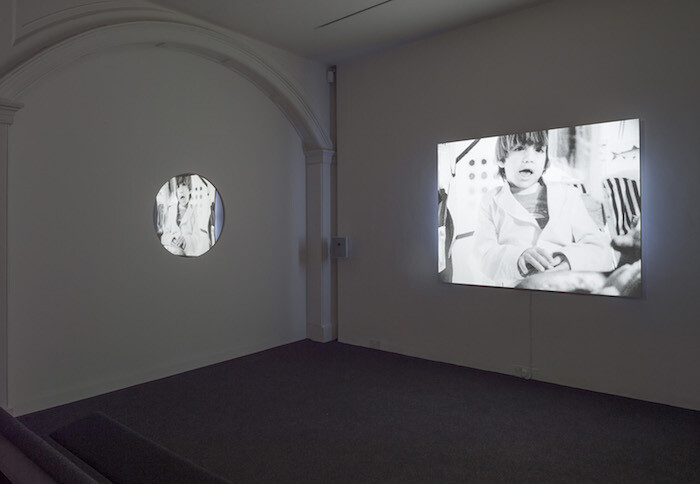

Back at Raven Row, Kidner’s “The Inoperative Community” stands as a welcome counterexample to these tendencies. Devoted solely to the moving image, it fulfills Morgan’s notion of a critical reflection on the conditions of display. Indeed, this is a central concern of the exhibition, as is hinted at by a one-way mirror encountered soon after entering, through which one can observe spectators seated in front of a projection of Leslie Thornton’s epic serial Peggy and Fred in Hell (1984–2015). “The Inoperative Community” provides an opportunity to look at films, but it also prompts us to look at how we look at them. The exhibition is split into two parts: seven works are generously installed in the various rooms of the gallery with comfortable seating, and a further 19 are shown in a cinema space with excellent perceptual conditions, holding approximately 30 viewers and constructed especially for the exhibition. Scheduled screening times are available for both on Raven Row’s website, with the cinema program changing daily and repeating weekly.

This makeover of a gallery into alt-multiplex might prompt one to question if “The Inoperative Community” should have taken place at a cinema instead. But it is key that the exhibition makes an argument for the importance of the movie theater from within the art context (where its specificity is too often forgotten), while simultaneously using the flexibility and temporal possibilities of the exhibition format to maximum effect and insisting that it can provide an appropriate context for concentrated viewing if deployed properly. Certainly, it would have been preferable to see Lav Diaz’s eight-hour Melancholia (2008) or Anne Charlotte Robertson’s Five Year Diary (1981–97) in a cinema rather than installed in the former domestic spaces of Raven Row, but what cinema would show them every day for over two months—and for free? Given that they are accorded the space, seating, and darkness they need, the trade-off is fair.

What does it mean to look at the cinema from the side of art? And what does it mean to look at the legacy of 1970s political filmmaking from the vantage of the present? “The Inoperative Community” positions itself at the intersection of these questions, asking how one might conceive of the relationship between the forms of collectivity that inhere in particular spaces of exhibition and the (im)possibilities of community imagined within the works on view. The cinema, after all, is a communal space in a manner the gallery will never be; as the filmmakers included in the exhibition knew well, it is with the cinema’s marshalling of collectivity that its promises and its perils lie. Within its reflection on these issues, “The Inoperative Community” succeeds in fulfilling the longstanding need for curators to move beyond the best-known works by the best-known figures and probe deeper into the immense wealth the history of film has to offer. And crucially, it does so while offering a quality of experience adequate to the quality of the work on view.

It is clear today that the infatuation with Hollywood that characterized the 1990s is largely over, but it would be a mistake to assume that this signals the end of art’s engagement with cinema tout court. Rather, the recent turn to the importation of the experimental documentary tradition and the representation of major figures of avant-garde film by commercial galleries should be taken as unimpeachable evidence of the development and persistent strengthening of the conjunction between art and cinema that began to take shape over two decades ago. The presence of cinema in art is enduring—but one hopes that the problems of presentation that have too often plagued it will meet a different fate.

For an account of the restoration process, see: Ross Lipman, “Conservation at a Crossroads,” Artforum (October 2013), https://artforum.com/inprint/issue=201308&id=43121.

Alexander Horwath, Film Curatorship: Archives, Museums, and the Digital Marketplace, ed. Paolo Cherchi Usai, David Francis, Alexander Horwath, and Michael Loebenstein (Vienna: Austrian Film Museum/SYNEMA, 2008), 133. For more on these debates, see: Erika Balsom, “Brakhage’s Sour Grapes, or Notes on Experimental Cinema in the Art World,” Moving Image Review and Art Journal vol. 1, no. 1 (2012): 13–25.

Jessica Morgan, “Too Much Too Soon,” Artforum (September 2015): 323.