Jessica Stockholder is an artist known for breaking conventions. Though her sprawling artworks are often referred to as installations, she defines her manifold combinations of color and everyday materials as sculpture.1 The two floors of Kavi Gupta in Chicago—which entwine a curated group show, “ASSISTED,” with her own solo exhibition, “Door Hinges”—resemble the aftermath of a funnel cloud, with debris scrambled in uncanny composition through two stories, a testimonial to the possibility in sculpture.

Since Rosalind E. Krauss’s canonical text “Sculpture in the Expanded Field” (1979)—which referred to the rise of earthworks like Mary Miss’s Perimeters/Pavilions/Decoys (1977-78) or Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty (1970)—the term “field” has become an abstract metaphor for a frame or context in which an artwork exists. Stockholder posits that the term should be expanded even further; more specifically, that sculpture can be anything “around which” or “through which” the body can move.2 Reinforcing this development of language around contemporary sculpture, Stockholder elevates the importance of the preposition in communicating a wonder of form, as if terms like “above,” “beneath,” “beyond,” or “below” might even become materials in the construction of an artwork. Thus, building on the concept of how door hinges function, these works articulate the qualities of juncture, as disparate objects are brought together. This approach is most directly shown with Wall Hardware (2015), a calligraphic drawing of parallel and congruent marks in space. The drawing was turned into a set of color gradated metal plates and used to connect pieces of a freestanding wall to itself, and then also to a structural wall nearby.

An unfurling work, A Log or a Freezer (2015), connects the outside of the gallery to the inner halls and upper levels, beginning with a painted log affixed to the outer corner of the building with a thick hemp rope. In the entryway, mirrors, work-lights, and extension cables hang from walls bathed in vibrant swaths of color. Patchwork variations of paint—in crimson, cobalt blue, canary yellow, or mint green—extend onto the ceiling and down the sides of the walls. Connecting the color blocks down to the floor, a plush violet carpet—cut at angles to meet and mimic the shapes painted on the wall—softens the tread. The same rope, which ties the log outside, cuts through the ceiling in the entryway, and disappears again through the wall into the next room. It surfaces through a hole in the front of a chest freezer hung high on the wall, pinned there as if the log and the freezer miraculously balanced each other’s weight. Completing the piece, the erect pole of a city street lamp reaches from floor to ceiling. The top part of A Freezer continues in the same spot on the upper level, where the head of the lamp assumes human dimensions, leaning curiously over a clawfoot tub. All the accumulated energy and tension shines through the street lamp’s LED bulbs, coalescing in swashes and small drips of paint lining the inside of the tub.

Massive readymade objects—a pristine upright piano, a smart car from a local dealership, an industrial office desk—are tethered tight by Assist 1, Assist 2, and Assist 3 (all 2015), sculptures made of colored, cut, and textured metal. These sculptures cannot balance on their own, so are bound to their “supports” with ratchet straps and buffered with blocks of felt. Each Assist requires the existence of a bigger, stronger, more stable structure in order to exist in an upright, complete state. Furthermore, if the work is purchased, the owners have to provide their own support to allow the sculpture to take on its “true” form. One cannot exist without the other. As much as Stockholder’s work may be about upending the laws of physics, it is also about breaking through boundaries to activate connections in form and space.

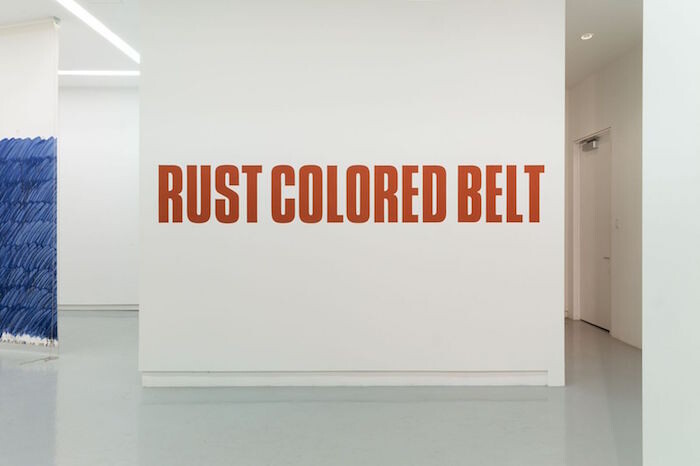

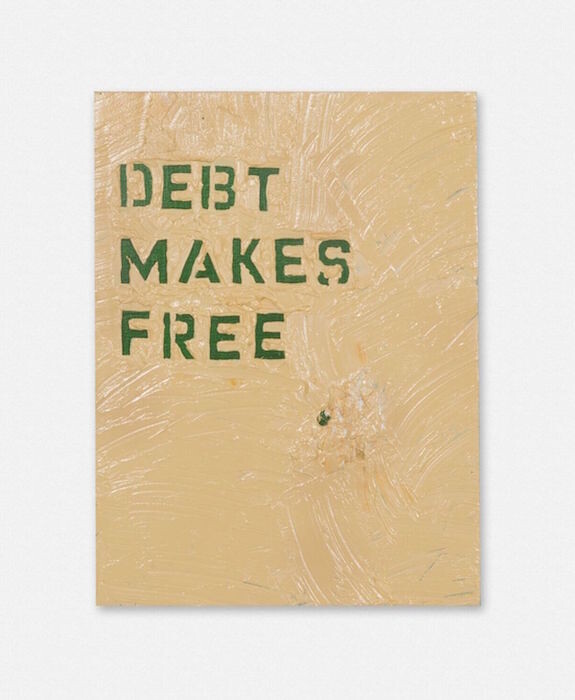

Likewise, the group show “ASSISTED” connects works by sixteen sculptors and painters as if inspiration and influence functioned like ratchet straps and hinges. Pieces from “ASSISTED” filter into Stockholder’s solo “Door Hinges,” and vice versa. Tony Tasset’s Cup 3 (2013)—a painted bronze trompe-l’oeil of a ripped Styrofoam cup—rests inconspicuously on a ledge of Stockholder’s Assist 3; around the corner, a surprise encounter with Sol LeWitt’s glacial fiberglass work Splotch #17 (2005) offers stability and reprise with its mass monochrome structure and soft, undulating dips and curves. Upstairs, steel and iron sculptures by Anthony Caro, bronze and marble wall works by Sam Moyer, and cat litter- or Soylent-encased domestic objects by Nancy Lupo enter into conversation with one another and with figurative paintings by Laylah Ali, cartoonish paintings and formal play by Patrick Chamberlain, and typographic works on paper by Kay Rosen, among others. Haptic textures, bright colors, and dynamic shapes cycle around the exhibition space, eliciting a call and response between artworks of one generation to the next. The exhibition combines artists who studied under Stockholder at the University of Chicago or Yale—such as Lupo—with those who—like Caro—have informed her own practice. The lineup is both an homage to artists whose work expands definitions of sculpture and a trip inside Stockholder’s mind.

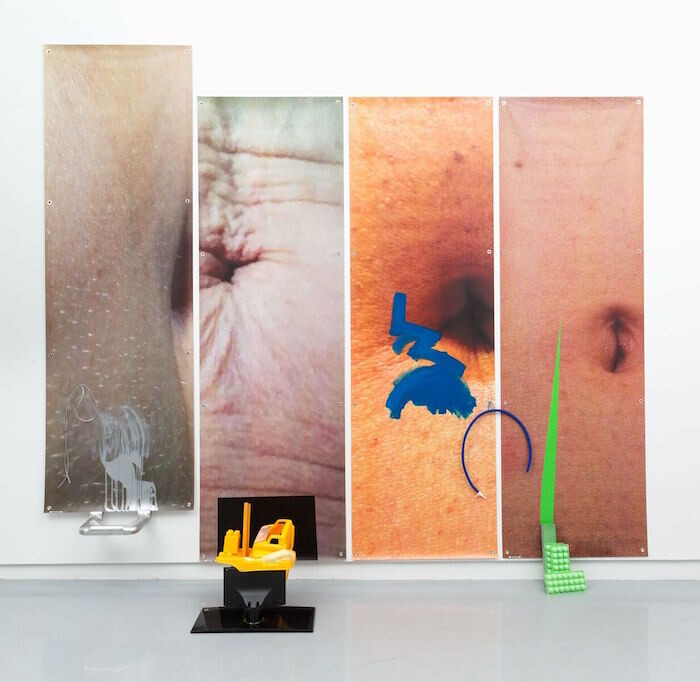

Set within the group show, Stockholder’s wall work Cracks Belly (2015) includes four vertical photo banner close-ups of belly buttons—flecked with paint and with an assortment of small colorful objects either attached to the images or on the floor in front of them—which brings navel-gazing to mind. While the term carries undertones of narcissism, in the context of this show it suggests another reading. Barring outdated and fetishized notions of outsider artists, or the manic ego toiling away in the studio alone, the reality is that artists need communities. The umbilical cord is the nourishing connector between individuals, and a reminder of how one body generates another. Like hinges and supports, it helps one form to influence, support, and bring to life another.

Jessica Stockholder, “Franke Forum: Jessica Stockholder on ‘Parallel Parking’” University of Chicago, 14 May 2014. Lecture. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KTMevRHvODk.

Rosalind E. Krauss, “Sculpture in the Expanded Field,” October, Vol. 8. (Spring, 1979): 30-44.

Rosalind E. Krauss, “Sculpture in the Expanded Field,” October, Vol. 8. (Spring, 1979): 30-44.