In a diminutive space in San Francisco’s financial district, the tradition of representing the vast landscape of the American West is extended and reinvigorated by Richard T. Walker and Letha Wilson. The natural and the manmade collide in Walker’s multimedia sculpture the other side of meaning something other than this (2015) and Wilson’s three photo-based wall works. Formally connected through repeated slanted lines and hints of geological forms, the pieces in the exhibition reference the past while operating very much in the present. Tied to conventional art forms like straight photography and landscape painting, the works nevertheless resolutely deny medium specificity through an unorthodox juxtaposition of materials.

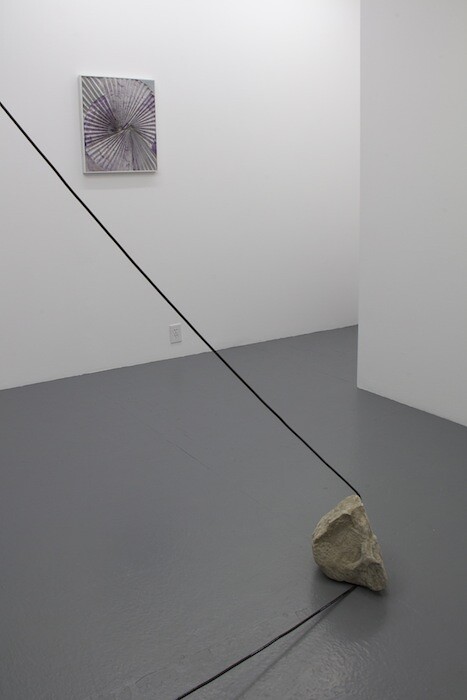

A glowing white neon tube rises from a bass amplifier, draws the stark outline of a mountain across the gallery window, and returns into a pedestal holding a walkie-talkie balanced on an unremarkable rock that depresses an “A” note on a Casiotone keyboard. A similar, slightly larger rock several feet away is bounded by a thick black cord that stretches up to the ceiling and then hangs down, weighted by an inverted microphone. The rocks, collected in Nevada, connect the mechanical sculpture to the natural environment. The subtle sound enveloping the small room is created by using effects to alter both the note emanating from the keyboard and ambient noise picked up by the microphone (including from the neon in the sculpture and the gallery’s fluorescent lights), combined with a recording of the artist’s voice made in the desert. This lonesome, almost plaintive, tone represents a human presence in the midst of outdated technology and primitive natural forms. Walker has spoken of his interest in the romantic sublime, and with this work, humanity becomes overwhelmed by the grandeur of nature, expressed through machines that reveal their own functions. The crude inner workings of the sound element remind the viewer of the inadequacies of manmade technology in relation to the processes of the earth itself.

On the walls hang Letha Wilson’s Nevada Sunrise Wall Sundial (One Line) (2015) and Nevada Sunrise Wall Sundial (Two Lines) (2015), hand-pleated photographs of the sun coming up over the silhouette of a mountain range, soft yellow fading into shades of blue. Steel armatures intersect the compositions, alluding to the shadows of a sundial. Wilson references iconic photographs of the American West by artists like Ansel Adams and Carleton Watkins, eroding their hackneyed status through the addition of the mark of the artist’s hand and a harsh industrial material. The accordion folds and steel strips render the photographs three-dimensional and make evident the relationship between the artist and the environment. Like Walker’s imperfect sound recording, Wilson’s handmade folds expose the vulnerability of the individual in nature.

In the context of San Francisco, the third work by Wilson, Nevada Concrete Folds (2015), a cement rectangle whose pleats fan out from two slightly off-center points, resembles a much smaller, more controlled homage to Jay De Feo’s The Rose (1958–66), which originated in an apartment not two miles from Capital. The process of creation is quite different for the two works, but the end results share a similar blurring of flatness and three-dimensionality. De Feo obsessively added and subtracted thick paint to build up a rough, dense surface punctuated by a grayscale starburst in the center of an eleven-foot-tall canvas, whereas Wilson transferred a photograph of the Nevada desert onto cement and framed the 22-inch work with a neat white aluminum border. Nevada Concrete Folds shares a stark heaviness with The Rose, countered by a paradoxical fragility, hidden here in pale purple marks and delicate edges.

“The Distance” is marked by this tension between cold manmade elements—neon, musical equipment, cement, steel, black cords—and allusions to nature—mountains, geological formations, the movements of the sun, the open desert. Both artists continue a tradition of imagining the artist’s place in the landscape, focusing on the process of transformation over static images. Nestled among high-rise buildings, the gallery nevertheless experiences changing natural light throughout the day that affects the visitor’s visual experience of the work, a shift mirrored in Wilson’s two photographs of sunrise and the sound fluctuations in Walker’s work. The two bodies of work in “Distance” arose from conversations between the artists, who are friends; although distinct, in the space of the gallery they interact seamlessly, bounded by the low distorted voice of Walker, the movement of light, and a shared affinity for the American West.