Chaotic and dense, lively, spirited, and in some senses logistically miraculous, the 2015 Jakarta Biennale takes its cue squarely from the political and geographic condition of Indonesia as an “archipelago state”—a nation comprised of a loose and idiosyncratic cluster of 922 inhabited islands. The exhibition trains its focus simultaneously on the political condition of the multi-ethnic post-colonial nation within the tides of globalization, as well as on the material and ecological state of being of its people, islands, and waters themselves.

This condition of forging together the contradictory forms of the archipelago and the nation-state is one that is linked in Indonesia to Third Worldist histories, which trace the efforts of decolonizing nations to develop an alternative to the expansionary European blocs of the Cold War. Following independence from the Dutch in 1947, Indonesian president Sukarno led a process of nation-building that sought to imagine a country united in anti-colonial defiance and strengthened through its internal differences. The 1955 Afro-Asian conference in Bandung marked a high point of this optimistic era: a moment in which Indonesia could imagine itself as the world center of an alternative planetary politics, and a decade before the Suharto-led military coup and the loss of between 500,000 and two million lives in anti-communist purges.

The unanswered question of political alternatives looms large across the Biennale. It is announced in its many socially engaged and activism-oriented installations, and is often set against the backdrop of environmental crises. It is tempting to add to the exhibition’s title “Neither Forward nor Back: Acting in the Present” a further subtitle: “Third Worldism in the Era of Climate Change.”

Perhaps the Jakarta Biennale suggests that answers are to be found among a new generation. For its 2015 edition, the team takes the experimental form of a “Curator’s Lab” drawing forward six young curators from across Indonesia and led by experienced biennial curator Charles Esche. Together they represent an impressively broad geography: Anwar Rachman, based in Makassar, the capital of South Sulawesi; Asep Topan and Irma Chantilly from Jakarta; Benny Wicaksono from the east Javan port city of Surabaya; Riksa Afiaty from Bandung; and Putra Hidayatullah from the historically separatist Islamic north-west province of Aceh.

Given this bold and risky move, it is impressive that the expanded team achieved such a large and logistically challenging project. Certainly its diversity can account for the widespread geographic inclusiveness of this edition, a feature which also marks its distance from the Biennale’s founding in 1974 as a national painting exhibition.

The “state of the archipelago” is at its base the condition of being mediated by water, and water as a motif binds much of the exhibition—providing its infrastructure not so much as a scaffold but rather as a persistent pulse. The immediate ecological significance of water is made urgent in local Jakarta artist Tita Salina’s raft of reclaimed plastic titled 1001st Island—The Most Sustainable Island in the Archipelago (2015), as well as in Dutch artist duo Bik Van der Pol’s Guarding the River project (2015). This latter work saw the pair collaborate with the Surabaya Riverside Residents Association in their struggle against eviction, producing a video installation with hanging diagrammatic prints. In these instances the environmental and social significance of water is direct and literal. The convergence of the life-cycles of water and of humans is diagrammed in the banners of the Surabaya residents, while appearing symbolically in Salina’s dank-smelling response to the Jakarta municipality’s proposed 32-kilometer seawall as a solution to its flooding and housing issues.

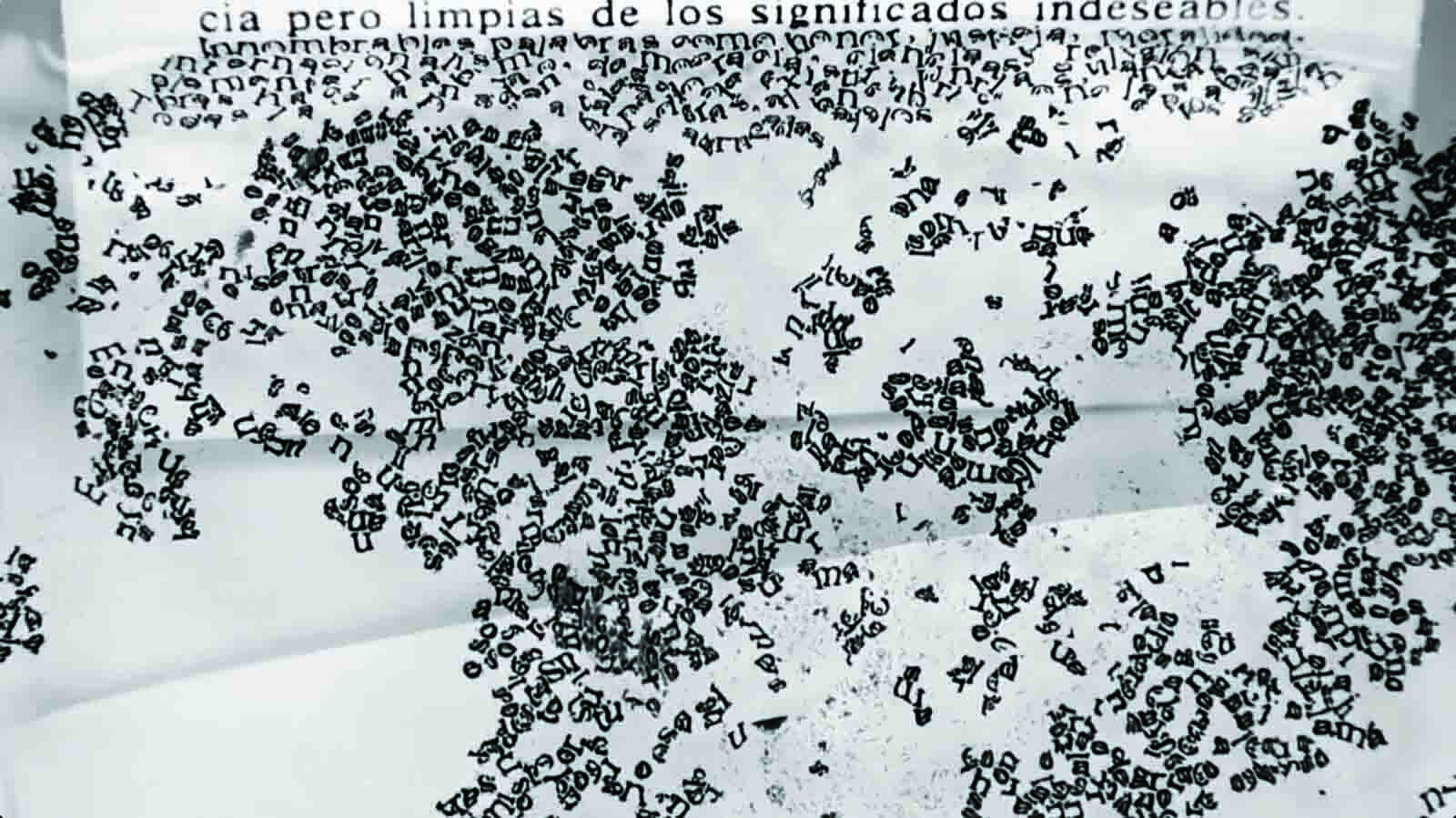

The fluid metaphor of water also emerges as seepage, deluge, and submergence—such as in Oscar Muñoz’s single-channel videos Ciclope and Distopia (both 2011), in which rows of typography float free of the page, sliding onto the surface of water and into an island chain of non-signification before swirling down a drain, as though lost to a one-eyed view of history.

Although not a narrative of water itself, the imagery of blocked pipes and leaking taps subtends Idris bin Harun’s epic mural Bhoneka Tinggal Luka (2015). The piece is a six-meter-long indictment of state violence, corporate exploitation of coal resources, and local corruption in the historically separatist province of Aceh, of which the artist is a resident. Its title is a play on the national motto “Bhinneka Tunggal Ika,” meaning “Unity in Diversity,” which is replaced by a détournement that translates to “wounded puppet.” Across a series of cartoon-like panels that greet the visitor through one of the Biennale’s two entrances, bin Harun depicts the drainage of Acehnese lifeblood to support a Java-centric political edifice.

Such internal borders are significant in Indonesia, not only in the struggles of the Acehnese but also in West Papua and the now independent nation of East Timor. The presence of internal borders complicates the statist nature of Third Worldism as it was expressed in Bandung in 1955, whose organizing principle was the nation-state. This challenge returns throughout the Biennale, troubling the dynamic of fragmentation as a narrative of crisis or of flow.

Richard Bell’s Embassy (2015), for example, stakes a position for First Nations land claims and sovereign rights. The large army tent of Bell’s installation references the Aboriginal Tent Embassy, erected opposite the seat of the Australian parliament in Canberra in 1972 by Aboriginal activists, and that stands as the country’s longest continual protest. As a symbolic echo, the tent both claims presence and offers a space of dialogue, playing host to a video that lampoons attitudes among white Australians (Broken English, 2011).

The greater context of Australia’s political presence in the region—and, in particular, Australia’s construction of a kind of negative archipelago of offshore Pacific detention centers for deported refugees—is the subject of Basque artist Juan Pérez Agirregoikoa’s installation The Natural Rights (2015). It features a cage draped in banners hailing football teams from separatist enclaves of Europe, as well as imagined teams from detention centers on Nauru, Manus Island, and Christmas Island. Next to these, a banner jeers Australia’s current deterrence campaign in the region: “No way, you will not make Australia home.”

Numerous works throughout the exhibition feature this kind of agitprop tone, making the exhibition a challenging one to read with an outsider’s eye. In addition, the Biennale has the strong sense of being as much an intervention into a local cultural politics as anything that is recognizable as an exhibition in the conventional sense. It tends to offer few images, but rather fragmentary flows and dense composites that the viewer must navigate and decipher. Such narratives sprawl across national, local, personal, ecological, and mythical registers with the chaotic ease of a tropical downpour.

Perhaps the true image of the Biennale was that of the opening night itself: an event without VIP lists or red carpets that counted an audience of around 6,000 visitors by its end. It was a night in which many video installations suffered for periodic power outages and viewers for lack of ventilation, but that nonetheless featured a blistering program of performance, live music, and light installations. Decidedly not invested in art’s preciousness, the Biennale seemed pleased to be trampled over by a sweaty and informal crowd.

Facing the main entrance—where audiences surged in and out with the unfolding performance program—the calm and savvy figure of legendary nineteenth-century anti-colonial Betawi bandit Si Pitung stood watch throughout the night. Depicted in a mural by Jakarta-based painter Aparilia Apsari (The Struggle, 2015), his figure stood almost as tall as the entrance itself. Holding a cigarette casually to his mouth Pitung slouched forward with a wry smile, emanating the pleasure of silent and subversive victory. In Apsari’s portrait, the folkloric figure is imagined to have just won a battle with the sea itself. Along with the cigarette he carries over his shoulder the tail of an enormous and frothing wave—a super-human presence that both follows and looms ominously behind him.