Ângela Ferreira occupies a special position in the history of artistic approaches to archival practices. One of the pioneers of research-based strategies at the very beginning of the 1990s—before these strategies had a name and long before they became a widespread (sometimes jaded) paradigm—the artist also applied her archival impulse as a new critical tool for sculpture, rooted in expanded and ethnographic procedures. But what marks Ferreira out in the contemporary art world is that her work often concerns the region of sub-Saharan Africa and, more specifically, South African and Mozambican realities inflicted by the troubled history of colonization, post-colonization, and apartheid.

Ferreira’s biography1 might help us to understand her geographical focus but not the complexity of her work, which is never informed by an “I” but driven by the antagonisms of historical materiality. This collective subject is the product of an extensive research, mediated through artistic and broader cultural structures that uncover negotiations between local cultural specificities, popular art, and modernism’s episodes. From this mediation new narratives emerge, offering oppositions to the historical processes of assimilation.

Ferreira’s current exhibition at Galeria Filomena Soares pursues such an approach, though we must recognize a difference in her archival methodology. Until now she has only scarcely presented the materials from which her work derives as part of her installations; here, for the first time, they are given equal standing with the drawings and sculptures that surround them. Further, the archival data assume such importance that the artworks reaffirm them, embodying their formal structures. Nevertheless, what is at play is a critical and enthusiastic way to approach the political within the artist’s own framework.

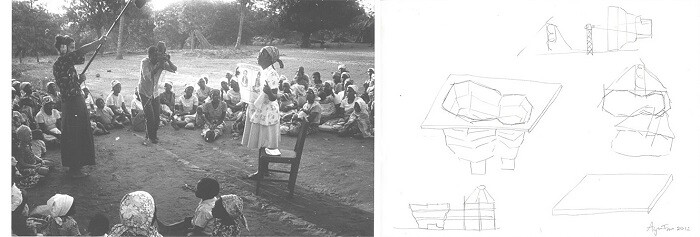

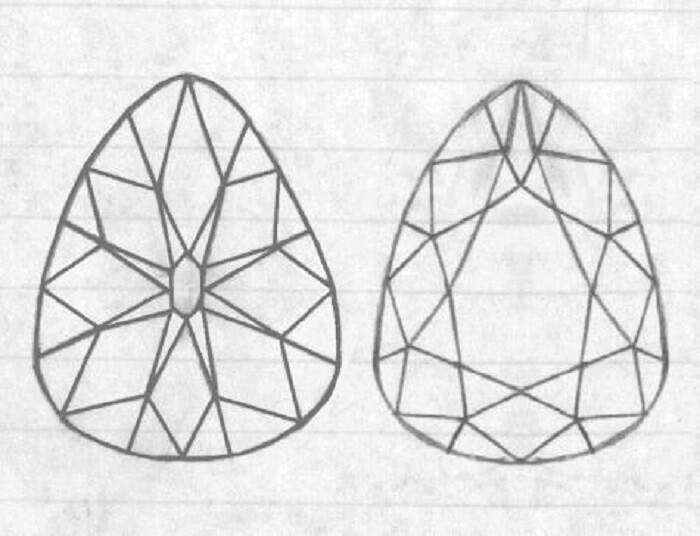

Hung on the walls are sets of visual documentation—collages, diagrams, prints, photocopies, or handwritten information—that register four different references separated by time and space: Robert Smithson’s drawings Towards the Development of a Cinema-Cavern or the Movie Goer as Spelunker and Underground Projection Room (Utah Museum Plan) (both 1971); Jean Rouch’s Super 8 film workshops in Maputo (between 1976 and 1978); the Kimberley (1871) and Cullinan (1902) diamond mines in South Africa; and the Chislehurst Caves (c. 1250) in London’s suburbs.

They are not obviously related, but their interwoven distribution in the space reveals one common feature: holes. From this particularity, the artist drags out a polyphonic conversation in which each reference acts as a negative mirror of the other, leading the viewer into a productive and unexpected set of dialectical correspondences. The photocopies of Smithson’s drawings, for example, present wasteland cavities as places animated by entropic qualities that could be used to reinvent the cinematic apparatus in critical response to the rationalist schema that governed modernity.

When our attention turns to the archival images that document Rouch’s film project, Smithson’s expression of “a truly ‘underground’ cinema” in his cinema-cavern drawings2 is given new meaning. As it leaves behind its literal connotations and opposition to film industry conventions, this idea of an “underground” art enters, along with Rouch, into the realm of political didacticism. The workshops organized by the cinema vérité filmmaker in the aftermath of Mozambican independence in 1975—within the Center of African Studies at Eduardo Mondlane University and with the support of FRELIMO3 cultural policy—sought to bring cinema with a social program into the lives of local communities. In this vision cinema would serve as a device engaged with the construction and distribution of social services—healthcare, housing, or education—in a new socialist society, freed from colonial power. A society that would soon face a devastating civil war. From these different cinematic utopian visions a common critical position against “progress” and imperialism suddenly emerges; two modern capitalist ideologies that reappear, ghostlike, in the documentation of the South African diamond mines, which remain under the control of multinational mining companies as De Beers or Petra Diamonds.

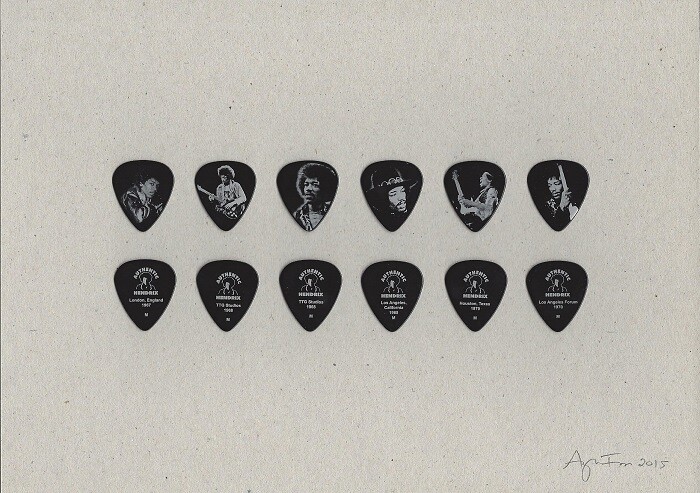

But if these mines—signs of slavery and oppression—haunt the above cinematic projects from which they want to separate themselves, their brutal holes are also haunted by other references. London’s Chislehurst Caves, once quarries for chalk and flint, also served as the music venue where Jimi Hendrix premiered “Stone Free” in 1966. A color print shows its interior, while a collage made with a set of Hendrix’s guitar picks establishes a formal analogy with a diagram of The Star of Africa, which was at the time of its discovery at the Cullinan mine the largest uncut diamond on record. Hendrix’s unclassifiable music—jazz-rock-R&B—and ambivalent lyrics come to mind, too, as a model of libertarian subjectivity that tends to resist the very processes of biopolitics, even when this politicization of communal and individual life embraces revolutionary purposes and other forces of coercion.

While these caves now also perform the role of tourist attractions, the group of drawings and sculptures that complete the exhibition seems to counteract the general amnesia promoted by the entertainment industries. The drawings integrate the formal elements of each cited reference—hollows, terraced lands, underground cinema booths, stairs, piles of mining waste, turntables—while the sculptures fuse them into a visual language that mixes the legacy of constructivism with sci-fi projections. Made of fiberboard, wood, iron, aluminum, and PVC, these works engender architectural and laboratory equipment prototypes that await new uses. We can only hope that they match the critical meaning that their forms seem to promise.

4 The Mozambique Liberation Front fought Portuguese colonialism from 1962. After independence, FRELIMO’s leader Samora Machel become the first president of Mozambique.

Ângela Ferreira was born in 1958 in Maputo, Mozambique. She grew up and studied in Cape Town, South Africa, and now lives and works in Lisbon, Portugal.

This conception is also part of Smithson’s essay “A Cinematic Atopia,” published in Artforum, September 1971 (cf. Robert Smithson – Le Paysage Entropique 1960/1973. Marseille: Musées de Marseille; Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux, 1994, 322)

The Mozambique Liberation Front fought Portuguese colonialism from 1962. After independence, FRELIMO’s leader Samora Machel become the first president of Mozambique.

The Mozambique Liberation Front fought Portuguese colonialism from 1962. After independence, FRELIMO’s leader Samora Machel become the first president of Mozambique.