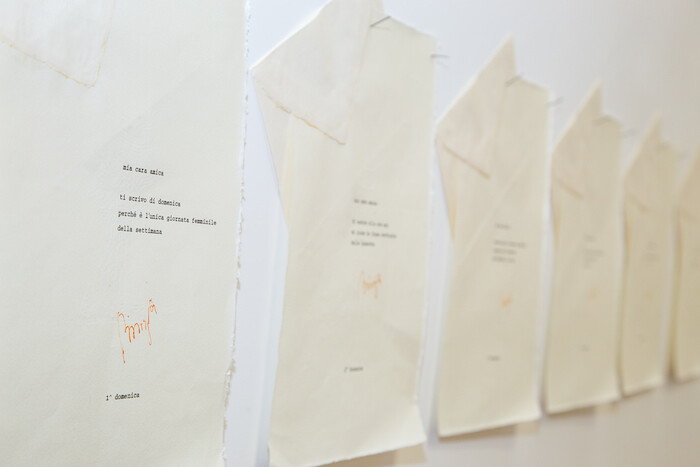

“My dear friend, I write you on domenica [Sunday], because it’s the only feminine day of the week.”1 “My dear friend, solitude or company?” “My dear friend, tonight I danced salsa forever.” “My dear friend, I hate the static nature of electric lights.” “My dear friend, I prefer daisies.” “My dear friend, I still believe in people.”

Once a week for all the 52 weeks of a year, artist and poet Tomaso Binga (b. 1931) sat down at her desk on Sunday to type and sign a letter to herself. A small reminder, of the same sort we now hurriedly type on our smartphones in order to transfix ephemeral ideas, names, bits and pieces, as if a machine-generated disposable note could protect us from the fading of individual memories. Binga chose instead to write on carta amalfitana, a precious handmade paper manufactured in Amalfi since the Middle Ages, so durable and costly it is usually reserved for wedding announcements. The result is Ti scrivo solo di domenica [I write you only on Sundays] (1977), a sequence of 52 letters and envelopes, now neatly pinned to the gallery walls to form a candid horizontal line, a personal calendar where poems, instead of numbers, mark the passing of time. Outside the windows—kept open when I visited, so that the sheets were gently rattling—the buzzing street life of Piazzetta Nilo, in the historic center of Naples, dispensed its daily dose of sunlight, run-down beauty, crumbling architecture, noise, and smells, in sharp contrast to the silent exhibition rooms (where Tiziana Di Caro moved last spring, after seven years of activity in the nearby coastal city of Salerno, where Binga was born). In 1977, the year recorded by Binga with her festive “room of her own” made of words and elegant paper, the clamor outside must have been deafening: Italy was shaken by the student movement and feminist new waves, riots, police killings, terrorist shootings of the so-called Anni di piombo [Years of Lead]. And yet, she preferred to focus on daisies and dances. Or maybe just pretended to.

Binga belongs to a generation of Italian artists who employed visual poetry and Nuova Scrittura [New Writing] to highlight the silencing of certain subjects within language and communication. Like Ketty La Rocca, Lucia Marcucci, Anna Oberto, to name but a few, she reacted to the muteness imposed on female voices by turning from writing to readings and performances, in order to embody language within an individual physical presence. It was an urgent matter of Materializzazione del linguaggio [Materializing language], as poet Mirella Bentivoglio titled the women-only group show she curated for the 38th Venice Biennale, in 1978, where Binga exhibited alongside Cathy Berberian, Irma Blank, Agnes Denes, Maria Lai, Mira Schaendel, and Mary Allen Solt, among many others.

The exhibition at Tiziana Di Caro pays homage to Binga’s pioneering efforts to make space for herself beyond the marginalized role assigned to women artists at the time; these efforts peaked in the late 1970s, when Binga chose to adopt the male name she still uses. On Wednesday, June 15th, 1977 at Campo D gallery, in Rome, the artist invited friends, relatives, and fellow artists to attend Bianca Menna e Tomaso Binga Oggi Spose [Bianca Menna and Tomaso Binga Just Married].2 Upon arrival, the public found two little framed pictures. In one, the artist was dressed as a young bride, holding a bouquet of white flowers—an actual photograph of the artist, who then went by the name Bianca Puciarelli, at her wedding in 1959 to Filiberto Menna, one of the leading Italian art critics and academics of the postwar scene. In the other image, she appeared as Tomaso, her alter-ego-as-artist, dressed in a black suit and tie, wearing large glasses, hair slicked back, with an office typewriter and some documents at hand.3 Binga declared she intended to celebrate the official union of her two selves, “after a due period of engagement.” Unlike Adrian Piper, who a few years before had assumed the identity of a black man (The Mythic Being, 1973-75) and took “him” to the streets to target the stereotyping of gender, racial, and social roles, as well as to test “what would happen if there was a being who had exactly my history, only a completely different visual appearance to the rest of society,” Binga was more interested in parodying male privilege.4 “I chose this male name […] because I needed to gamble with the male world. It was ironic and ludic, but it was also a strong provocation. […] In conclusion, it was a reversed and paradoxical protest.” I wonder if she knew that 77 years before, in writing “A Letter to Artists, Especially Women Artists” the British painter Anna Lea Merritt had remarked, deadpan, that “the chief obstacle to a woman’s success is that she can never have a wife.”5

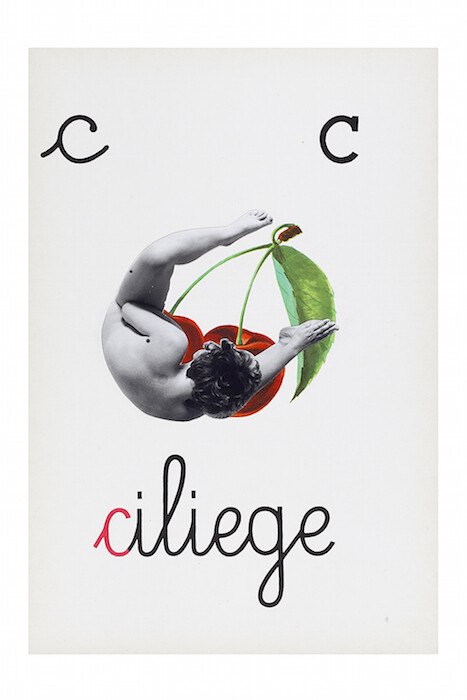

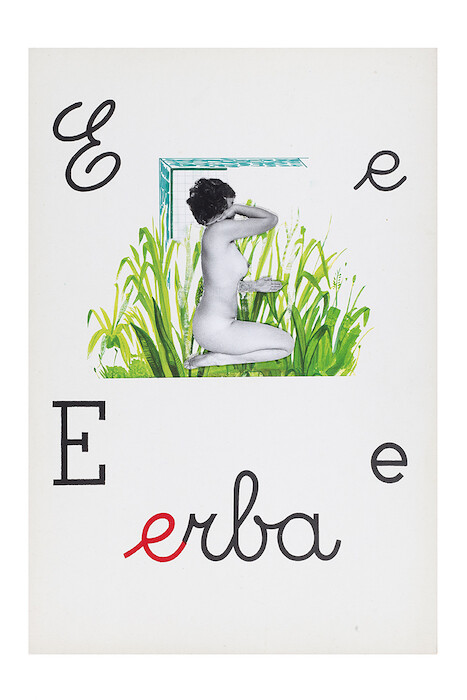

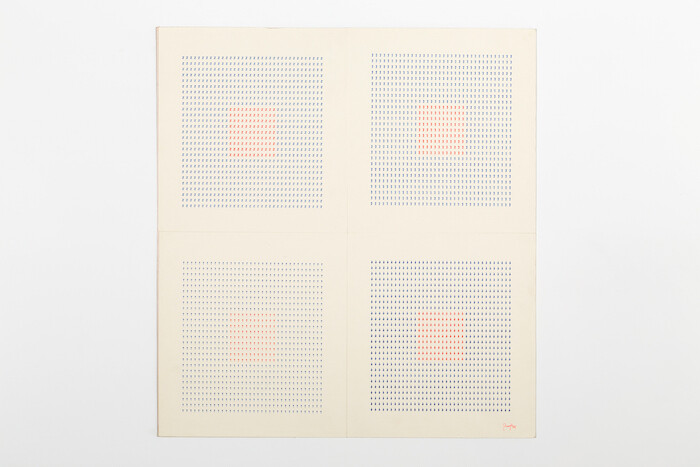

Binga’s touch is light, tongue-in-cheek, and poetic. In another series of works on show, Alfabetiere Pop [Pop Spelling-Book] (1977), she cuts out photos—shot by another artist friend with militant feminist leanings, Verita Monselles—of her own naked body, postured like different letters. She then collaged these images onto the candy-colored illustrated cards used in elementary schools to teach the rudiments of reading and writing to kids, in an attempt to infiltrate language from the start. The series of her Dattilocodici [Typecodes] (1978) in black, blue, and red, the mandatory colors of typewriting, recalls the poems of Henri Chopin, but narrate very little. The letters are superimposed to create indecipherable alphabets and arbitrary icons, used to draw abstract grids and squares. Only rarely, here and there, a phrase is allowed to emerge, like in Ho bisogno di una casa nuova [I need a new house] (1978), again to speak about domesticity and its possible constraints: “I need / a new house / I need / a bed and four chairs / I need / an empty cupboard / I need only a few pans in the kitchen / I need / a life without memories.”

In Italian, all other days of the week end with -dì (day) or the suffix -o, both masculine.

In Italian, the title clarifies that both partners are women.

Marta Serravalli, Arte e Femminismo a Roma negli anni Settanta (Rome: Biblink, 2003), 79.

Adrian Piper speaking in an excerpt from Peter Kennedy’s film Other than Art’s Sake, 1974, viewable at http://www.adrianpiper.com/vs/video_tmb.shtml.

Anna Lea Merritt, “A Letter to Artists: Especially Women Artists,” Lippincott’s Monthly Magazine, vol 65, no 387 (March 1900): 463-469.