Astute observers in the art world were puzzled by Mike Kelley’s move from Metro Pictures to Gagosian in 2005. It seemed as if he had left a warm and supportive family concern for the cold new world of unfettered late capitalism. In the wake of the artist’s 2012 suicide, there was further bewilderment when his estate moved to a different mega-gallery, Hauser & Wirth. Why on earth, wondered my editor when she commissioned this review, would they move from one international blue chip gallery to another?

This posthumous exhibition at Hauser & Wirth provides one answer. Organized in cooperation with the Mike Kelley Foundation for the Arts and former MOCA curator Paul Schimmel, now director of Hauser & Wirth’s new Los Angeles branch, the show is revelatory: smartly put together with love, insight, and admiration. They knew exactly what to show, how to show it, and how to give it context and sense. They even tried to cast a hopeful light on Kelley’s dark vision. Speaking at the press view, Schimmel said Kelley was dealing with an “epic otherworldly pursuit and the surrealist tradition.” His “sculptures of the unconscious” were “recycling the sense of monumental failure,” seeking “a place to go home.”

Kelley’s previous New York show with Gagosian was a curiously disappointing installation of paintings and monochrome panels at the gallery’s 24th Street space in 2009. Titled “Horizontal Tracking Shots,” it had to do with his “Extracurricular Activities Projective Reconstruction” series (2000-2011) of videos based on high school yearbook photos, and also with the frontality of stage sets. I remember leaving that show with the sense that it was an incomprehensible mistake. With vast expanses of opaque monochromes, indistinct cartoon figures, and hermetic videos showing traumatic YouTube footage behind a stage-prop wall, the exhibition seemed to turn its back on us. Most critics ignored the show. It got little press except for an Art in America article by Peter Plagens on the sorry condition of the art world, who predicted that Kelley is “headed for a big fall.”1 Plagens noted the disjunction between the “indifferently rendered cartoon characters that look as though Sesame Street ran through Chernobyl” and ”a curiously antiseptic Greenbergian-formalist rationale for Kelley’s dystopia.”

By the time of Kelley’s thrilling posthumous MoMA PS1 retrospective in 2013, everyone had forgotten about that show. The traveling survey was expansive, generous, and full of experimental works that spun off every which way, revealing Kelley’s prolific genius and widespread influence. Referring to childhood traumas and comic book heroes, they included his amnesiac schoolroom models and plans, his installations of bedraggled plush toys and grungy crocheted blankets, and much else. It proved Kelley to be the pioneering artist of the abject we thought we already knew. And it ended with a return to Kelley’s childhood roots: Mobile Homestead (2011), the movable reconstruction of his childhood home in Detroit, the John Glenn trash-encrusted memorial (the Detroit school Kelley attended was named for the former astronaut)2, and the icily perfect “Kandors” series (1999, 2007, 2009, 2011). Yet the retrospective never quite came together: it was as if some cohesive central core was absent.

The Hauser & Wirth exhibition provides that missing core. It focuses exclusively on the “Kandors” project that preoccupied Kelley in the final years of his life, from 1999 to 2011. Kandor, of course, is the capital of the planet Krypton, where Superman was born. Shortly before Krypton’s destruction (and the infant Superman’s voyage to earth), an intergalactic supervillain named Brainiac, who traveled from world to world stealing cities and miniaturizing them and their inhabitants, stole Kandor and its six million inhabitants and imprisoned them in a bottle.

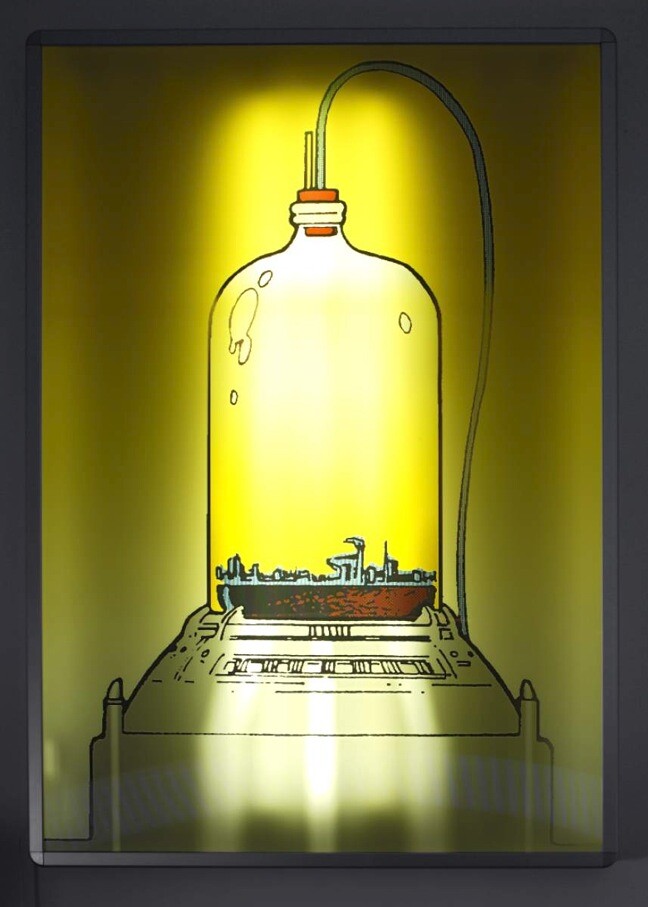

The project began in 1999 with the failed construction of an interactive website, Kandor-com 2000, which would have provided a way for fans of Superman to connect with each other. Intended for “Zeitwenden,” a group show at the Kunstmuseum Bonn, it was cancelled due to lack of funds. Instead, Kelley staged a performance, the self-explanatorily titled Superman Recites Selections from “The Bell Jar” and Other Works by Sylvia Plath. Then Kelley, who was interested less in Superman than in spatial memory and interaction among disconnected individuals, decided to translate the two-dimensional world of the comic book into sculpture. The construction of the Kandors became, in Kelley’s words, “a mirror of the failure of modernism’s vision of a technological utopia.”3 Producing the glass bottles alone took five years; only one factory (in the Czech Republic) was willing to attempt to hand-blow bottles so large (some were over forty inches high). Then there was the matter of the color, the gas tanks, the sounds, and the individualized bases. Each of the twenty Kandors—consisting of bottle, base, shrunken city, gas tank, hoses, and video—was produced in five unique versions.

The current show opens with an array of miniature resin Kandors in delectable colors including kryptonite green (City 17, 2011) and glittering coal black (City 15, 2011), each glowing model lit from within—part amnesiac futuristic architecture, part stalagmite, part birthday cake—based on the diverse illustrations in different Superman comic books. A glowing purple gallery follows, with a trio of miniaturized cities in red, yellow, and blue, and a big red gas tank pumping frothing vapors into a bell jar (Kandor 4, 2007). The backlit lenticular Kandors in bell jars that line a passageway magically vanish and reappear as you pass.

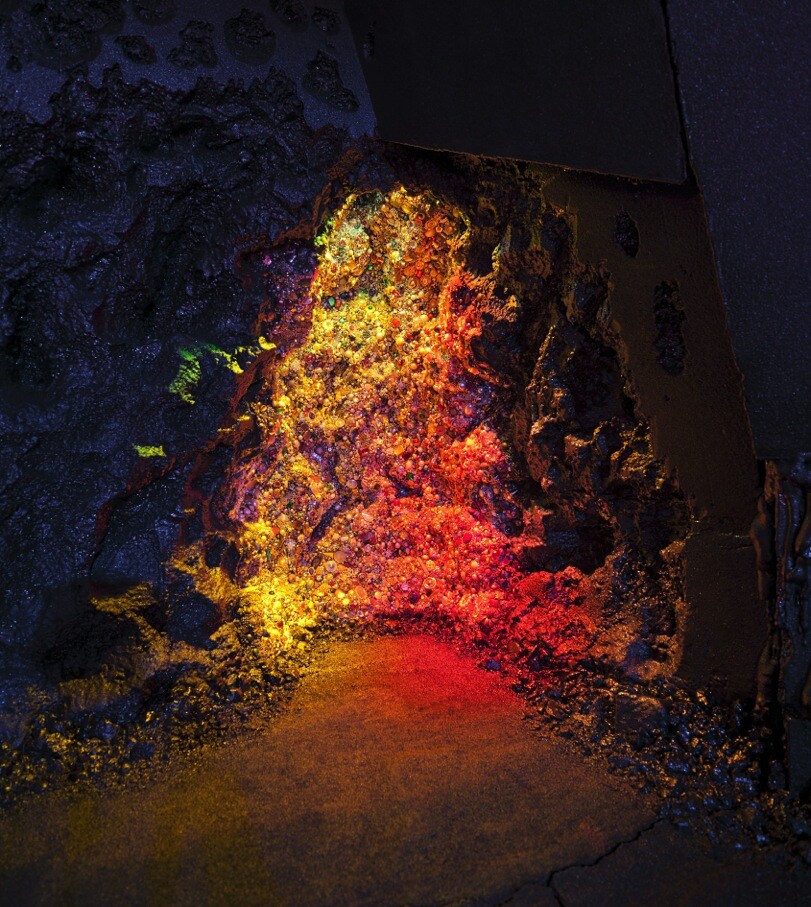

And then the show explodes into a full-scale cavernous installation of carbonized blocky fragments: Superman’s Exploded Fortress of Solitude (Kandor 10B (Exploded Fortress of Solitude), 2011). Suddenly the scale reverses: it is the viewer inside a dark cavern peering at a glittering Kandor shrunk into a bell jar. The vast space also contains large chains and handcuffs, and an ominous video, almost as demented as some of Paul McCarthy’s, titled Extracurricular Activity Projective Reconstruction #36: Vice Anglais (2011)—the last of the series—in which colorful characters do nasty things to each other within that exploded space. The final secret is one icy Kandor, Kandor 2B (2011), in a bell jar: unique, wax-coated, filled with glittering flotsam, flowers, and baby blue ribbons—like a gift for the innocent infant Superman. This cohesive show sheds light on Kelley’s state of mind and his preoccupation with the elusive nature of memory: claustrophobic, suffering a sense of irreparable loss, clinging like Superman to the remnants of that loss in a fortress of solitude.

At the time of Heath Ledger’s death in 2008, Jack Nicholson implied that playing the role of the psychopathic Joker in the latest Batman film had gotten to him—or into him. Perhaps something similar is true of Kelley, whose final works were consumed by the narrative of Superman and his nemesis. Superman was eventually able to catch Brainiac and take Kandor back. He kept the tiny city and its inhabitants alive in a bell jar filled with swirling atmospheres in his arctic Fortress of Solitude, hoping to find a way to expand it to its original size. It’s an apt metaphor for Kelley’s oeuvre, which delved into repressed memories, abuse, and alienation—not only of his childhood but of our culture.

Peter Plagens, “Production Values,” Art in America (January 2010): 41-42.

The full title is John Glenn Memorial Detroit River Reclamation Project (Including The Local Culture Pictorial Guide, 1968-1972, Wayne/Westland Eagle), 2001.

Mike Kelley, “Kandors,” in Rafael Jablonka (ed.), Mike Kelley: Kandors, (Munich: Hirmer, 2010), 53–60.