Madame Bovary losing silver, aluminum objects at sea. Madame Bovary losing an aluminum tampax at sea. Madame Bovary losing a Victorian doll at sea. Madame Bovary making pickles, painting bats, breaking porcelain. Madame Bovary posing as Salo, sitting in a Breuer chair, stitching pearls into her skin. Madame Bovary, in ornate frustration, creating a poignant display of ceramic plates with revolutionary motifs. This, and more, is what you might find if you follow Paris’s proverbial strumpets—its gotons1 Gustave Flaubert, Madame Bovary, 1857.]—down an old commercial passageway to Galerie Édouard Montassut. Situated in two mirrored spaces standing on opposing sides of the passageway, Goton & Montassut’s exhibition is an untitled marriage of minds, split half-way between its founding members: a self-proclaimed village wench, Eva Svennung, who runs the independent space Goton, and her co-signatory, who runs Galerie Édouard Montassut.

The exhibition—a bric-a-brac of objects equal parts domestic, lavish, emotionally void, and intentionally corrupt—is presaged by Svennung’s use of Flaubertian language. Madame Bovary is a pointedly unstated spirit conjured up in literary fantasy, weaving between the works her wanton commentary on the bourgeoisie: its failures, its endless repetitions, its antipathies, and apologists. She appears, for example, in Nina Koenneman’s carefully broken porcelains, Lithic Reductions 2, Lithic Reductions 10, Lithic Reductions 4, Lithic Reductions 6 (all 2015). The milky white shards read like casualties of domestic clumsiness but are actually the product of an exacting activity known as knapping: a method for creating prehistoric tools which has gained a following as a pastime. In this, Koennemann’s vitrified flints are ascetic fantasies, symbolic objects devoid of use value which become tokens of conspicuous leisure. Camille Blatrix’s Tosh (2015) takes this ornate idleness to another level of precision: the beautifully constructed, wall-hung maple and milkstone form recalls the crafting of artisanal objects intended for everyday use: a hand-carved toothbrush handle, maybe, or a mysterious digital device by the likes of Bang & Olufsen. Its context is unclear, though its intention as décor is not: Blatrix affixes on surface in an almost licentious exploration of the pathologies underlying design, and the subversions found in its perfection.

Elsewhere, appropriating a conservative aesthetic to confer courtliness on sexual desire, Bernadette Corporation’s Revolutionary plates (2004) trade subtle seduction for surface value. Each of the four ceramic plates, lips, and rims lined in gold, flaunts an assemblage of digitally printed pornographic images. Amidst these decorative designs of gaping vaginas and dick-slaps to the face is a single printed word, one for each plate: Liberté, Égalité, Sûreté, Propriété. This is commemorative merchandise of the kind that reduces history to commodity, and commodity—dressed up in perverse nostalgia—to dead-end indulgences disengaged from the possibility of further exchange.

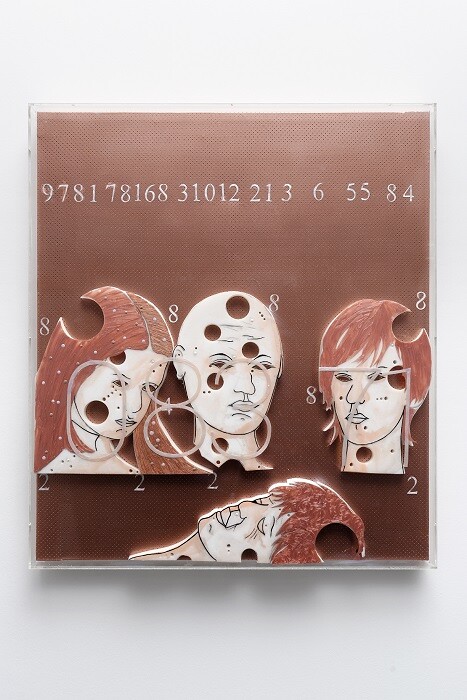

In a similar vein, Guillaume Maraud’s tableau vivant 9781781683101221365584888848222208371 (2015) is characterized by an exaggerated sense of surplus, not only in its excessive numeric title, but also in the fashion shoot gazes of the plexi-enclosed melamine foam portraits. Against a dusty, copper-toned PVC canvas, Maraud surrounds his characters in floating silver numbers, leaving them to strike a pose on a quite literal surface of value. Embedded into their nail-polish painted skins are small faux pearls: masochistic memorabilia, perhaps, of a society still fueled by the lingering desires and pretensions of the bourgeoisie. The mind meanders to Mme Bovary, with her mind set on purchasing M. Lheureux’s finest scarf—a feverish attempt to satisfy sexual cravings with material possessions. In this, she becomes dressed and decorated, so to speak, in the concessions of a libidinal economy. Trevor Shimizu’s cute, manic-depressive painting cow owl bats (2014), on the other hand, prods at the psychological loss of power that follows from participating in such structures. Painted (according to an anecdote dished out to me by Montassut) in a post-vacation period of distress, it is a lavish tantrum dedicated to leisure, its loss and its lasting impressions. That said, it seems significant to note that neither Maraud nor Shimizu’s work engages in droning critique, but honestly figures the whims and fancies of an ever-affective consumer society.

Perhaps what the exhibition unwittingly targets is precisely those trigger situations which lead us to promiscuous behavior—whether sexual, economic or otherwise. Other works, such as John Kelsey’s pencil-rendered Pasolini drawings, Salo I and II (both 2003); Melanie Matranga’s orgiastic globe of clay people interlaced in suspended (and somewhat purgatorial) acts of sex, communication, and consumption, Bad timing for lovers (2015); or even the displaced pickle shop, a grandmotherly survivalist initiative by Bill Hayden, Sam Pulitzer and Antek Walzcak, War Pickles II (2014), all point to a lascivious common existence—a pliable and fleshy modernity bent over by the forcing of economic exchange and its strong hand over the body.

To indulge in fantasy, these are works that could live inside the mind of Madame Bovary: depraved and domesticated by their surroundings, yet resolutely aware of the value of catharsis, of those mindless and pleasure-seeking pursuits which can reclaim the self from the structural desires of industrialized society. Yet Bovary, in pushing beyond the bored romantic traditions of her time, entered a social reality she didn’t control. Her liberation became a prurient search for self, a bourgeois escape at best, which expressed itself in the emptiness of the artisanal. The mélange of motifs, then, and the irrationality of the objects she amassed while in the midst of her affairs, became desire lines to her destruction. A trampled trail of objects that were seductive, fetishistic, perverse, and, in this, possessive of unspoken agency. Overblown with intent, it is possible to consider the artists at Goton & Montassut following Emma to her vanishing point: learning, in her wake, to circle bourgeois folly with a critical eye.

“Elle avait tant souffert, sans se plaindre, d’abord, quand elle le voyait courir après toutes les gotons du village et que vingt mauvais lieux le lui renvoyaient le soir, blasé et puant l’ivresse.” [“She had suffered so, without at first complaining, when she saw him running after all the village strumpets and that a score of disreputable places sent him back to her in the evening, worked out with pleasures and reeking of drunkenness.”