At the entrance to Lawrence Abu Hamdan’s “The All Hearing” a tape delay device perches on a plinth, its magnetic tape wrapped around an external spool (The End of Every Illusionist, 2013). Through the attached pair of headphones emerges the artist’s voice, its vowels lightly pressed by his Yorkshire upbringing, to tell us that noise pollution in Egypt’s capital has reached the proportions of an epidemic. The barrage of sound in the world’s loudest city is so constant, he intones, that it threatens not only the physical but the spiritual well-being of its inhabitants.

The vaulted ceiling above this listening post is speckled with the same red, green, and blue disco lights that, eight hours previously, had ghosted over my head at a Sicilian beach party. Here, however, the flickering projections are soundtracked not by synthetic Europop but by the beats emerging from rival boat parties along the river Nile, amplified through a row of speakers stacked neatly in the center of this narrow, high space (Gardens of Death, 2013). Songs bleed into one another as the microphone tracks the sounds of Cairo, recorded by the artist from a motorboat—an aural, waterborne equivalent to Taxi Driver’s celebrated montage of a ride through nocturnal New York.

Noise is both the theme and material of this exhibition, its form and content. Curated by Robert Leckie of Gasworks, London, the show’s guiding principle—that the accumulation of aural information degrades rather than adds to the sum of human knowledge—is reflected in its employment of compact cassettes as a medium for the transmission of sound. Each of the cassettes was purchased from a market in the Egyptian capital, and the works derive titles such as Gardens of Death from the sermons originally inscribed upon them. Those orations have now been buried beneath the artist’s re-recordings—whether of his own voice or Cairo’s bankside nightlife—and The End of Every Illusionist impersonates the effect by overdubbing the words to create an echo, an acoustic halo. We are reminded that beneath what we are listening to now are hidden messages, obfuscated instructions. “Overdubbed tapes,” the recording tells us, “cause memory loss.”

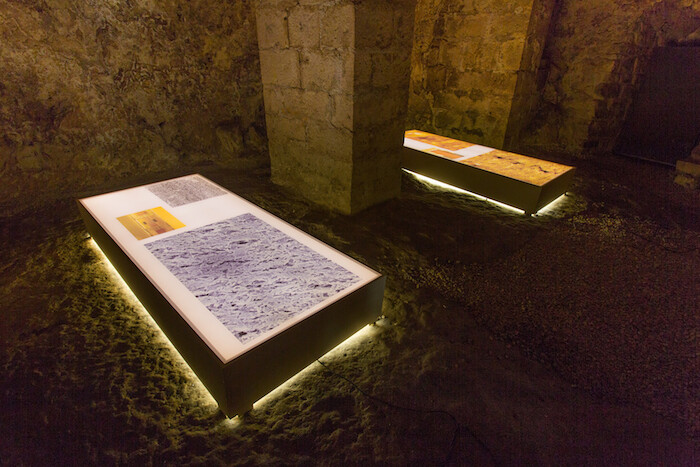

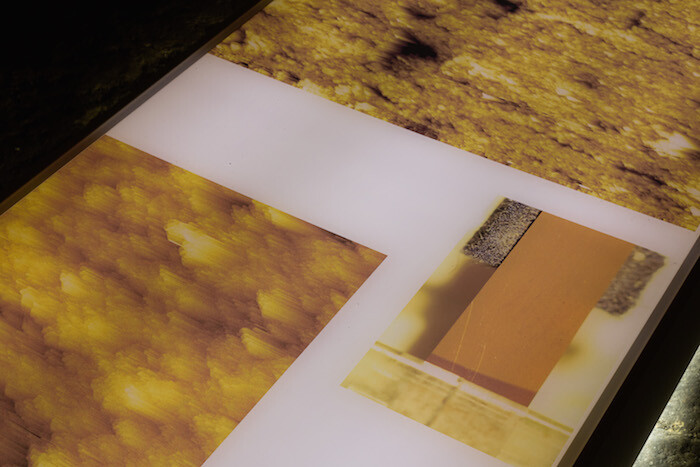

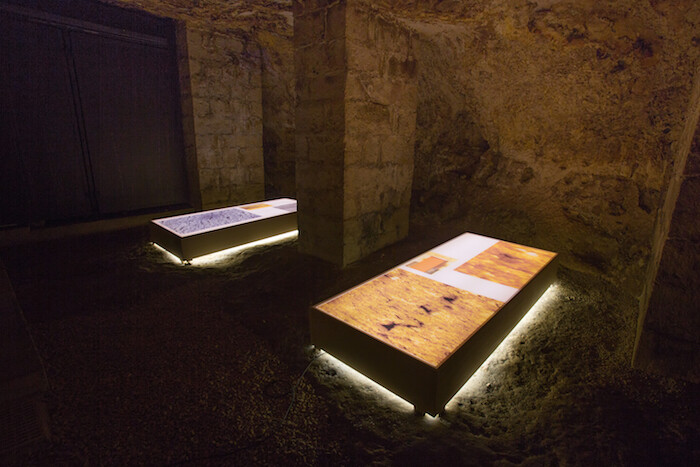

This process of loss through accumulation is literalized by a series of C-print photographs displayed on horizontal light boxes in the gallery’s back room, a rough-hewn cave of the type buried beneath many more recent residential developments in the ancient Sicilian town.1 Comprising magnified images of audio tapes’ magnetic strips, A Conversation with an Unemployed (2013) illustrates the decay in clarity that comes with the superimposition of numerous layers of information. On one side are tapes inscribed with a single track, their metal ribbons etched in clean, sharp patterns. On the other are their second-hand and third-hand equivalents, whose low-fidelity surfaces are pockmarked, scabbed, illegible landscapes.

Information abrades information, and The End of Every Illusionist alludes to the failure of forensic scientists to retroactively decode a section of the Watergate tapes that had been recorded over in order to obscure their original—presumably incriminating—content. Speaking about the superabundance of documented sound in a surveilled society, the artist has previously stated that invasive audio-recording technology functions “more like an emitter of noise than a receiver. It produces noise, and that noise is what mutes people.”2 The most effective means of censoring recorded sound is to overlay it with more sound. By chronicling everything, by making no distinction between purposeful and non-purposeful speech, we bury what is valuable beneath an avalanche of white noise. The competition of sounds through Laveronica’s connecting rooms effects a comparable confusion.

To address the epidemic of noise pollution in Cairo, Abu Hamdan invited two sheikhs to deliver sermons on the subject to the local populace. Their homilies were filmed and edited into the short film The All Hearing (2014), screened at Laveronica in an alcove adjoining the central space. Speaking into microphones that project their voices over mute audiences, the speakers warn against exposure to “too much noise.” The contamination of the urban environment by noise is symptomatic of a society in which, they chide, “we seem unable to control our voices, to say anything but empty words.” The determination of every individual to be heard makes it impossible to separate sense from nonsense, to parse meaning from sound. “Every noise that does not cause good,” one advises, “is as the braying of a donkey.”

The irony of the sheikhs’ use of loudspeakers to broadcast their counsels against noise is reinforced by several cuts to a song blasting out a paean to peace and quiet. That ambiguity extends to Abu Hamdan’s invitation to two religious leaders to pass judgement on who, and what, is fit to be spoken and heard—what constitutes “good” sound. In the premise that information is dangerous is the implication that it should be mediated—censored—prior to its consumption by the masses, a task traditionally undertaken by the clergy. In an autocratic society the state has exercised that function; in a democracy the mainstream press. This intelligently plotted exhibition leaves us, therefore, in a double bind: we are either overwhelmed by the superabundance of information to which we now have access, or are forced to rely upon mediators in whom so many of us have lost faith.

On the other side of the wall is the recently rediscovered Chiesa di San Nicolò Inferiore, a tiny subterranean cave church frescoed with Byzantine icons.

Basia Lewandowska, “Interview with Lawrence Abu Hamdan,” frieze, no. 160 (January-February 2014): 114.