In an age of financialization, notions of value are increasingly abstracted, constructed from algorithmic equations as opposed to distinct processes or materials. As Franco “Bifo” Berardi writes succinctly of our era: “monetary value produces more monetary value without being realized through the production of goods.”1 This observation indicates a departure from the objects through which capital has traditionally been conducted.

In the heart of Hong Kong’s business sector, where the wheels of multinational corporations churn alongside luxury boutiques, Edouard Malingue Gallery’s exhibition “Clamour Can Melt Gold” looks to gold, a medium that is at once anachronistic and foundational to current conceptions of value. Taking its title from a Chinese proverb popularized by the country’s forefather Sun Yat-sen, “Clamour Can Melt Gold” suggests an aspirational fervor that speaks to the power of the masses against great obstacles and also, perhaps inadvertently, to the mutability and porousness of that which has an established value. Following this sentiment, in the exhibition, gold is attended to as both a highly coveted, symbolic, and fetishized object as well as a tool of exploitation and power.

Easing the viewer into the subject, Hong Kong artist Sarah Lai’s Styling Index (2015) examines the visual rhetoric of ubiquitous high-end jewelry advertisements found in Hong Kong through a pleasing array of stock image-like compositions. These feature women with snow-white complexions caressing opulent accessories, accompanied by aspirational terms such as “eternity” and “sincerity.” Printed in oil on canvas and closely resembling posters and billboards, aberrations in the images—backward text or small portions that have been sprayed over and concealed—are hard to notice at first, making for an uncanny effect. The works indicate the degree to which such images are omnipresent and seamlessly embedded into everyday life. Other artists in the show, Danh Vo and He Xiangyu, stage material interventions that inversely inject gold into common objects, the former with a Coca-Cola box lettered in gold leaf (Coke, 2014) and the latter with a 24-karat egg carton bearing a single egg (200g Gold, 62g Protein, 2012).

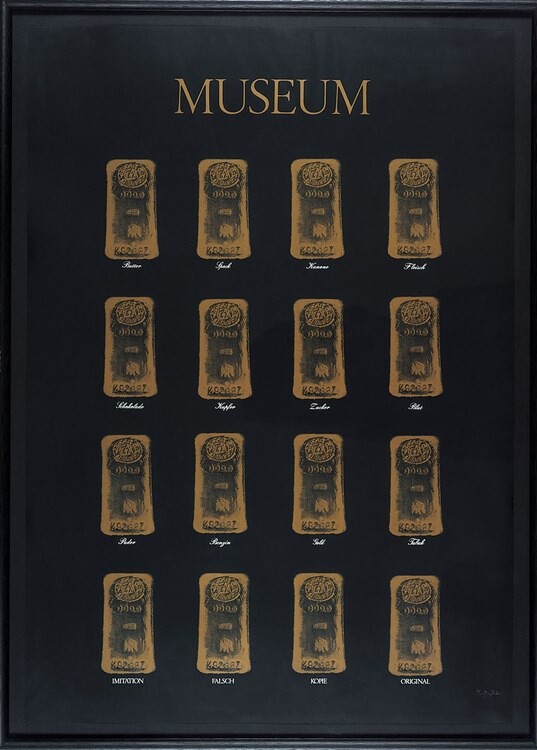

The symbolic or metaphoric value of gold is revealed in Marcel Broodthaers’s diptych Museum, Museum (1972), referring to his infamous conceptual museum Museum of Modern Art, Department of Eagles (1968–71), in which works never appeared in one place at once, nor were they typically art objects, therefore refuting the logic of a conventional collection. The screenprint on two sheets shows a stack of golden ingots that the artist produced to support the museum, selling each at a price double its market value at a time when currency was still tied to a gold standard. The work dispels nostalgic notions that economic value has ever been attributed according to an impartial standard.

Kwan Sheung-chi and Wong Wai-yin’s To Defend the Core Values is the Core of Core Values (2012) looks again to the symbolic capital of gold, this time in the context of Hong Kong politics. The artists produced a golden coin embossed with the emblem of the city. When the work was first exhibited, viewers were invited to submit what they considered to be Hong Kong’s core values by way of a public survey and enticed by the chance to possess the coin itself. Upon receiving it, the winner would then be made to decide between throwing it into the harbor as a metaphorical gesture or keeping it. In the accompanying video, which along with the coin is on display at the gallery, a famous local politician who goes by the name Long Hair stands at the precipice of the sea, contemplating whether or not to cast the giant golden coin into its depths. In a surprising and dramatic twist, he turns his back on the waves, muttering something about how the party could use the gold to pay its debts, thus affirming capital’s firm hold in the game of politics.

Suggesting a more substantial discussion of the exploitative nature of gold is Alfredo Jaar’s documentary work Rushes (1986–2015), which depicts workers in a gold mine on the coast of Brazil. In a darkened room, images are presented in a lightbox whose contents reflect back toward the viewer through a mirror, rendering them ghostly and illusionistic. While nodding to the unseemly aspects of gold acquisition, this majestic work isn’t quite as revealing as it is aestheticizing. Conversely, Regina José Galindo’s Looting (2010), placed in an understated corner by the elevator exit, inscribes the legacy of colonial domination onto the human body. In the video, Galindo undergoes dental surgery in order to remove gold fillings she has carried in her teeth from Guatemala to Berlin. Gold is portrayed as both an object through which value courses, as well as a material with the ability to permeate and mutate. The extracted shimmering bits serve as a strikingly poetic analogy for power relations and subordination, recalling vividly the domination of Latin America by European colonial powers in the sixteenth century.

Franco “Bifo” Berardi, The Uprising: On Poetry and Finance (Los Angeles: Semiotext(e), 2012), 18.