September 5–November 1, 2015

“Saltwater: A Theory of Thought Forms” takes its name and inspiration from the eponymous book Thought-Forms (1901) by the Theosophists Annie Besant and Charles Leadbeater, who, after the death of the prominent Theosophist Madame Blavatsky (1831–91), expanded and re-conceptualized her attempt to extrapolate Newton’s theory of color into a syncretic cosmology.1 According to Besant and Leadbeater, “thoughts are things,” and as such, they can manifest as visible auras. Thought-Forms is a detailed account of “what kind of thing a thought is,” in which Besant and Leadbeater document the “spiritual vibrations” which emanate from ideas, emotions, and sounds as visual shapes, colors, and forms. The book, whose illustrations are exhibited in what curator Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev calls “The Channel”—the nucleus of the exhibition, installed at Istanbul Modern, the biennial’s central venue, which plays a function akin to that of “The Brain” in Documenta 13—could be aptly described as a “a sort of spiritual synesthesia, as much a religious act as a neurological one.”2

Materialization of psychic phenomena was a widespread obsession in late nineteenth-century occult circles. Around the 1870s, a plethora of psychics would claim to act as conduits or transmitters, which, much like a radio frequency receiver, could capture cosmic vibrations said to manifest in a fashion similar to electromagnetic waves. Odd as it now may seem, before Alessandro Volta invented the battery —allowing the electrical to exist independently from the animal—electricity had never been conceptualized as a purely physical phenomenon. Vitalism—which was still mainstream science in Victorian times—believed there was an intimate connection between electricity and animation,3 and the field of physiology lumped together research that would later be divided into three clearly distinct branches: the scientific domain of neurophysiology, the emergent field of electromagnetic technologies, and the para-scientific circles of esoteric beliefs and séance gatherings.

Christov-Bakargiev describes “The Channel” as a Klein bottle, a unisurface volume, possessing neither inside nor outside, but the biennial’s operating metaphor is the wave––a form which can manifest itself as a physical phenomenon (electromagnetic wave), as a brain function (sodium channel), as an atmospheric anomaly (the aurora borealis captured in the photographs of Norwegian mathematician Fredrik Carl Mülertz Størmer [1874–1957]), or as political tragedy (the recurring waves of refugees that hit the shores of Lampedusa or Bodrum daily).

Stretching a continuity between Besant and Leadbeater’s cognitive synesthesia and the visualization of brain functions, the Thought-Forms illustrations are shown opposite to the scientific drawings of synaptic connections, Thalamic Afferent Axons in the Human Cerebral Cortex (circa 1889) by Spanish neurobiologist Santiago Ramón y Cajal (1852–1934)—himself an amateur artist—and to a model of the mirror box (1993) created by neuroscientist Vilayanur S. Ramachandran (b. 1951), which is commonly used to treat phantom-limb syndrome in amputated soldiers. Ramachandran is perhaps best known for theorizing that phantom-limb syndrome is the result of cortical remapping, linking the puzzling phenomena to the emerging theory of neuroplasticity, which claims that the brain is a dynamic organ whose functions can be re-wired throughout the course of adult life, but more pertinent to the exhibition’s context might be his take on metaphors as a form of associative synesthesia—a topic, along with sensory protheses and brain-machine interfaces,4 also tackled by several other speakers at the Hotel Splendid Palace conference, “Thought Forms and Brain Waves—Neuro-Aesthetics and Art,” held on September 3.

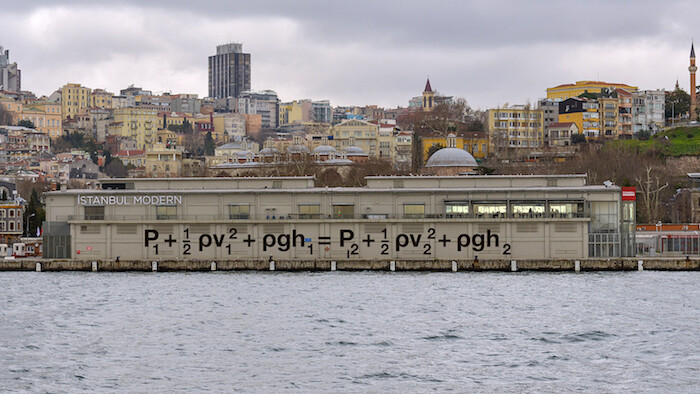

“Saltwater” is conceptually dense, generating a filigree of fecund associations, and carefully staged, stretching from the Beyoğlu district, where the main venues are located (Istanbul Modern, Galata Greek Primary School, and the Italian High School), to the picturesque scenery of the Princes’ Islands. Besides its influence in what is known as Vibratory Modernism,5 it is easy to see how the themes and tropes of Victorian Theosophy recur in contemporary discourses—from speculative realism to object-oriented ontology; New Age philosophy; Silicon Valley transhumanism or Scientology, all loosely predicated on the idea that thoughts are things. That said, neuro-aesthetics’ take on contemporary art is trivial, and Theosophy, though compelling, was an unwittingly stagnant theory (idiosyncratically, Besant was a feminist and a socialist while Leadbeater advocated masturbation, anathema in Victorian times) which combined Buddhist and Hindu traditions with Neo-Raphaelite aesthetics and a dash of Darwinism. Perhaps unsurprisingly, several works on view feel over-aestheticized and repetitive, displaying an excessive penchant for romanticizing Naturwissenschaft (natural sciences) and an overall illustrative approach to the exhibition’s concept. More elaborate are Ed Atkins’s Hisser (2015), a narrative of masculinity, swallowed by a sinkhole; Liam Gillick’s Bernoulli equation (in fluid dynamics, speed is inversely proportional to pressure) written on the Istanbul Modern seafront, Hydrodynamic Applied (2015); Susan Philipsz’s take on Guglielmo Marconi’s belief that sounds, once generated, continue to reverberate ad infinitum across media, Elettra (2015); Anna Boghiguian’s installation detailing the salt cycles The Salt Traders (2015); Prabhakar Pachpute’s miners, whose heads are turned into electrical sockets, What We Have Left is the Blue Water (2015); a political manifesto by Inland, (an ongoing project by Fernando García-Dory), declaring that “the rural is the new queer;” or Esra Ersen’s video-essays on Bulgarian and Turkish nation-building after the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, A Possible History I: When Thinking Some Play with the Moustache, Others Cross Arms (2013), and A Possible History II: Turkish Heroes, Chinese Knick-knacks (2015).

Overall, what the exhibition lacks is a work that would tie together its several conceptual threads—in a way like what Pierre Huyghe’s Untilled (2011–12) did for Documenta 13. The cathartic staging of Adrián Villar Rojas’s The Most Beautiful of All Mothers (2015) at the pier of the house Leon Trotsky once inhabited seems to point to that intention, but Villar Rojas’s Bilalesque animals lack the unsettling subtlety of Huyghe’s Kassel installation. Two of the works in “Saltwater,” Pierre Huyghe’s Abyssal Plain (2015–ongoing) currently under construction underwater, in the Marmara seabed, and Michael Rakowitz’s installation The Flesh is Yours, The Bones Are Ours (2015), reference the 1911 dog massacre in Sivriada,6 one of the Prince’s islands, a traumatic event which, it has been said, foreshadowed the 1915 Armenian genocide—but the concern “Saltwater” manifests for non-human actors is hard to reconcile with the exhibition’s deference toward neurobiology, a discipline built on the usage of animals as raw matter.

The biggest conceptual issue, however, is perhaps to be found in the exhibition’s residual Hegelianism, echoing the apparent belief that historically recurring forms are endowed with a higher form of consciousness than the one belonging to individual persons. Before the nineteenth century, the social was not an issue of primary concern for intellectual inquiry. Rather, it was seen as secondary to other problems, such as the nature of human consciousness or of the physical world.7 “Saltwater: A Theory of Thought Forms” maps the recursive movements between neuroscience, hydraulics, astronomy, electromagnetism, botanics, and aesthetics. But by assimilating “waves of uprisings” and “waves of jouissance” to “electro-magnetic waves,” the exhibition lacks a representation of the social as an independent, irreducible domain of human experience.

When prompted by a member of the audience to address the email sent by some of the biennial artists (Pelin Tan and her ArtikIsler Collective, and Anton Vidokle) asking all the participants to shut off their work for 15 minutes to protest the breakdown of peace talks between the Turkish government and the PKK, the Kurdistan Workers’ Party, Christov-Bakargiev replied that though she supported whatever decisions the artists may make, in her view, all art forms are political. Though one may in principle agree, in the absence of a subject of collective enunciation, “the political” cannot be activated. We are left, instead, with what writer Orhan Pamuk refers to in his Eight Notebooks (2008–13), shown in “The Channel,” as mono no aware, a Japanese expression that literally means “the ‘ahh-ness’ of things.” Waves are a signifier for transience, and while the awareness of something’s impermanence heightens our emotional response, it also signals the futility of struggle: things are oblivious to their own demise.

Newton himself had identified seven colors to match the seven musical notes and the seven metals in alchemic theories, thus indigo is exceptionally included in his color wheel.

Benjamin Breen, “Victorian Occultism and the Art of Synesthesia,” in The Public Domain Review. Published March 19, 2014.

What Luigi Galvani called “animal electric fluid” or what Franz Mesmer named “animal magnetism.”

A rapidly developing field of neuroscience, which entails the incorporation of artificial actuators into brain representations.

The term “vibratory modernism” was coined by Linda Dalrymple Henderson. In recent years, several essays have been published which address the central role of vibrations in turn-of-the-century physics, physiology, spiritualism, and modern art.

In 1911, in a effort to modernize Istanbul, authorities gathered 80,000 strays and a left them to starve on a barren island, later selling the bones to a French industrialist for the production of soap.

Hayden White, The Fiction of Narrative: Essays on History, Literature and Theory, 1957–2007, ed. Robert Doran (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010), 74.