Tokyo’s Rat Hole Gallery is beside a church, apartments and a small park. Removed from the passing traffic, stairs from the street lead to a basement entrance hidden behind frosted glass. By locating them so precisely in the show’s title, Glasgow-based Andrew Kerr suggests the new paintings for his first Japanese solo exhibition have a more intimate relationship with the city they now call home, despite their origin being very distant.

This show picks up where his previous one—“The Other Shop” at Glasgow’s The Modern Institute in 2014—left off. Bringing three dimensions to painting, fixed objects are arranged to document chance moments. It is open to interpretation whether they are seen as flat examinations of a landscape or as landscapes themselves—are these objects or pictures? As in “The Other Shop” the emphasis is on context. Yet in a city like Tokyo, where everything is equally important and simultaneously forgettable, context is a vague and uncertain principle.

Next to the entrance, a single painting on Japanese paper hangs like a reconsidered ukiyo-e, bereft of the figures and scenery we associate with it. The main space holds five small canvases whose sequence is interrupted by four larger, more sculptural works positioned at eye-level (all works Untitled, 2015). Hung in groups, they suggest a subtle rhythm and relationship reinforced by color, form, and common perspective. The background of one of the larger works is entirely purple and broken into smaller sections. Within it, a square of canvas sits to one side, overlapping a darker block of color. Combined, they draw the eye in and frame perspective, like looking through a wayward camera. The outside edge is cribbed together from blond wood that seals the amassed painting, posing a question—where does the canvas stop and the frame begin?

Another large work, hung vertically and seemingly inside-out at the far end of the room, interrupts the whole installation. From afar, it does not appear very dramatic yet up close, it snaps from a somber landscape into a cityscape with a shock of yellow. While the entrance painting invites you in, this work abruptly asks that you leave or take another look around. The eye’s tour of the exhibition is disrupted by vivid objects that compel you to look again.

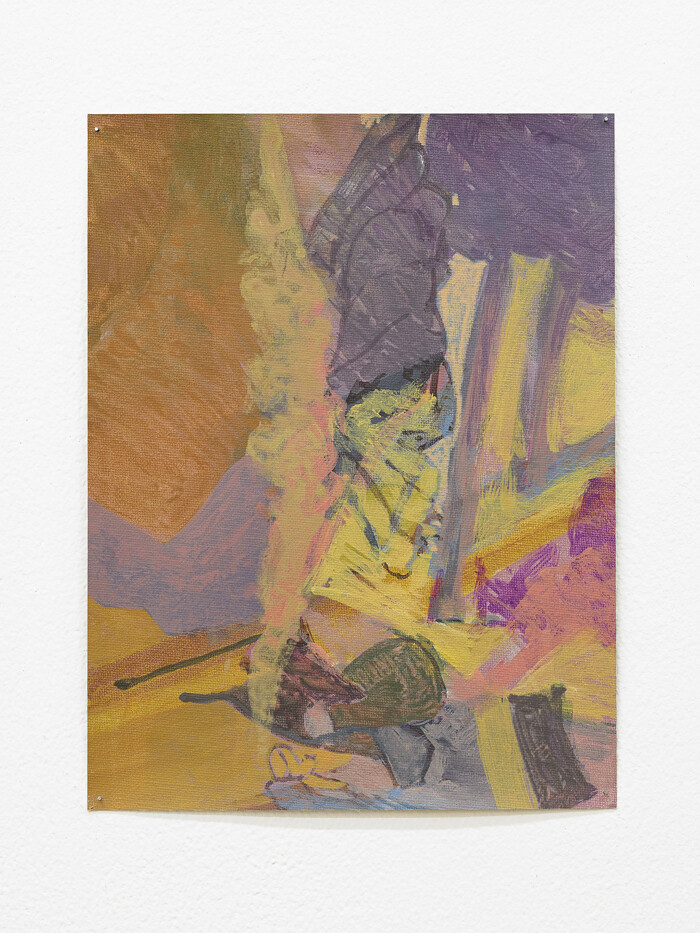

The five smaller paintings are tacked to the wall unframed, while the larger works incorporate offcuts of black mounting board riddled with the trace of old fixings and a collection of ex-material rescued from obscurity. Momentary detail is not rendered realistically. Pen marks are vaguely erased by thin brush strokes and further sharpened by blocks of brighter color. Each element is understood as visually uncertain, to “incoherently connect the incoherent cityscape… not to create a fusion but a confusion.”1

The show is filled with references that locate the works in art history as well as place. The Nabis, early Gauguin, even Arthur Dove are waypoints and markers. Dove’s abstract impressionism and Gauguin’s fondness for making copies of ukiyo-e prints share a loose and lethargic undercurrent, a ‘floating world” from which modern imagery is absent. Kerr’s painting is equally ambivalent, pointing at instances and objects that swiftly come into view and as quickly disappear. Loosely established scenery combines with clearly defined marks to suggest vacillation over how moments are best pieced together.

Having moved into a more generous-sized workspace back home, Kerr suddenly had room to include found material within, on top of, and around his paintings. These objects would find their way into his work as he queried the act of painting, and what it means to him. Kai Kähler writes that “against the background of art history the artist can no longer be just a painter or a sculptor. It has rather become the rule to work in more than one genre.”2 Kerr’s approach is to counter this by working modestly, defining territories that express “nowhere.”

The origin of Kerr’s painting is hard to pin down, despite its shared features with the exhibition’s immediate surroundings. The work feels anonymous in the same way that Tokyo appears restless, and tells little of what is being recorded or where it comes from. Yet the paintings hint that they will reveal themselves over time, an unravelling that continues long after the work is thought of as finished.

The summer heat and blasts of cool air shift and twist the paintings; they wilt but hold together. Kerr makes sense of material gathered in Scotland by presenting it in Japan, in a city nonchalantly cobbled together and built, like the work itself, on uncertain terms.

Kanemura Osamu, “The City, The Body and the Image,” Déjà-vu Magazine, No.18 (Autumn 1994): 93.

Kähler, Kai, “Notes on the Works of Andrew Kerr”, in Andrew Kerr (Edinburgh: Inverleith House, Royal Botanic Garden, 2011), 25.