On a long drive into the city our tour guide, a “colored”(1) woman and self-confessed strict Old Testament observer, railed against recent student activism at the University of Cape Town: “They pulled down the statue of Cecil Rhodes and he did more for the black people than they have done for themselves.” This is how it is with a certain generation, I’m told. Scratch the surface and the old hissing, prejudicial illogics of empire and apartheid can still be found. White English against white Afrikaners, coloreds against blacks, every self against every Other. These are tensions that compound social divisions, exacerbate the unequal distribution of wealth, and rationalize a brutal reality of social cleansing that gentrification seems too florid a word to describe. In a town this politically charged, what use are the subtle, indirect, and oblique forces of contemporary art?

“Speaking Back,” at Goodman Gallery, is offered as a possible response to teleological questions like the one above. In the guise of an exhibition as social interstice, a locus in which marginal and muted subject positions are given voice, the innovative and often startling works of 13 predominantly black African and African American women are installed as possible contributions to a notional forum. The result of time spent by curator Natasha Becker between the US and South Africa, “Speaking Back” is pitched as something more vital and pertinent than a standard curatorial exercise in selection and connoisseurship. Rather than a collection of discrete works it is a gathering of perspectives, a multivocal public assembly with a shared common purpose to enunciate a suppressed subject position. At least, that’s how it is on paper. The reality is quite different.

The core flaw of “Speaking Back” is its inability to convincingly transform single works into a cohesive group. It is a problem that stems from Becker’s selection criteria, determined by race (mostly black) and gender (exclusively female). The hazard in bringing disparate individuals together according to some external criteria—whether class, race, sexuality or gender—is that the process invariably forces a reductive condition of essential commonality on an otherwise disparate array of artists and artworks. Do Kara Walker, Ivy Chemutai Ng’ok, and Candice Breitz have that much in common other than their gender? To her credit Becker realizes this. In the printed gallery text she writes, “we have a tendency in exhibitions of work by women to generalize the artists as merely exemplars of a gendered collective (…) their singularity annulled.” Awareness of this curatorial pothole doesn’t, unfortunately, mean Becker sidesteps it completely.

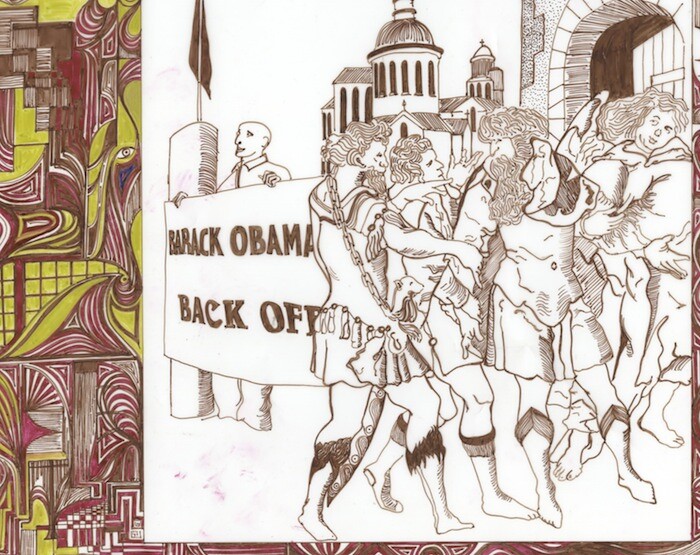

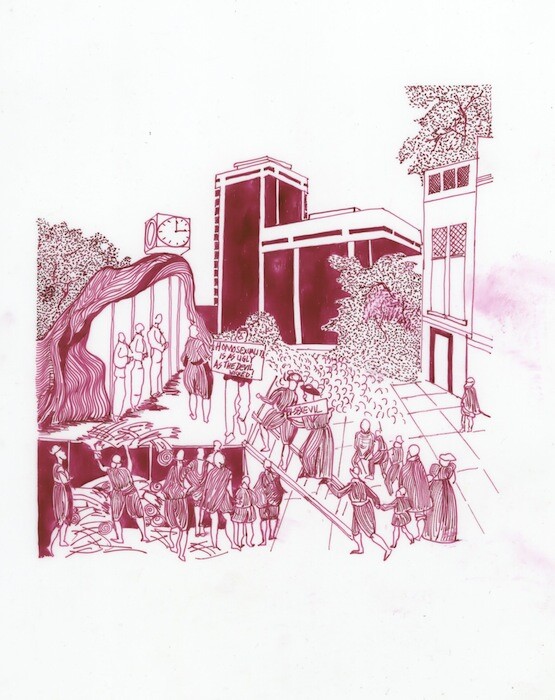

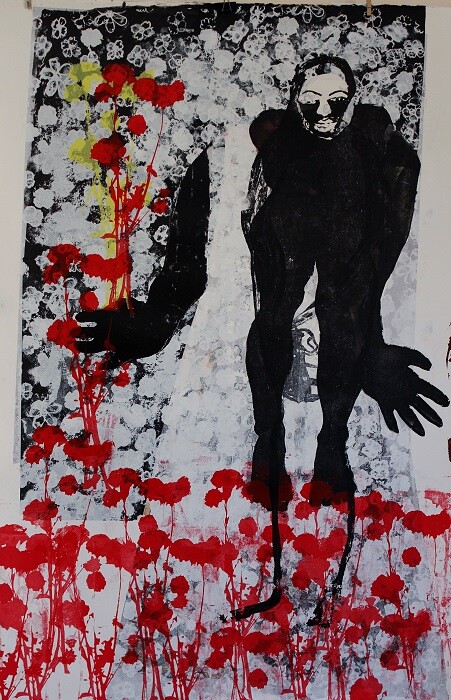

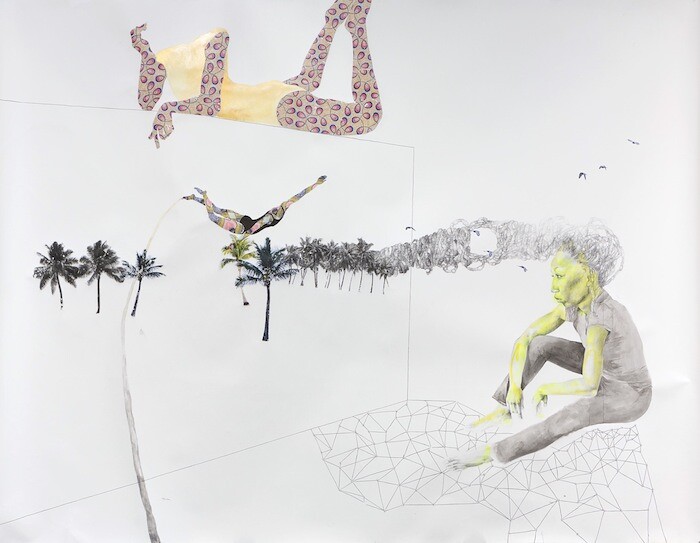

Push this aside, however, and there are some compelling works here. New Jersey-based Adejoke Tugbiyele’s fine-lined ink drawings of protests and public gatherings combine contemporary politics with seventeenth- and eighteenth-century figures and fashions. In As Ugly As The Devil (2014) what looks to be a crowd of Roundheads are gathered to protest against homosexuality, while modernist buildings loom in the background. Barack Obama, Back Off (2014) sees a group of curly-haired, neoclassical fugitives from a renaissance history painting trundle past a single figure protesting against Obama. The message of historical Puritanism reemerging in today’s atmosphere of conservative center, center-right politics may not be complex enough for some, but the aesthetic results are compelling enough on their own. Zimbabwean Virginia Chihota’s paintings are darkly poetic visions of figures against abstract and expressionistic backgrounds. And Nigerian-born Ruby Onyinyechi Amanze’s large pencil and ink drawings—including the evocatively titled with the galaxy beneath her, she remembered the magic of soaring amidst coconut clouds (2014)—cover one wall with fantastic, zero-gravity visions in which figures dream abstract landscapes into being.

Becker should be lauded for seeking to create a dialogue between African and African American female artists. While Adrian Piper’s total disavowal of the conceit (see her withdrawal from the black performance art group show “Radical Presence” in 2013) was a necessary step to take in the US—where black art group shows can simply foreground the racial exclusivity of the art world (without tackling it), marginalize black artists, and simultaneously define a reductive black aesthetic—in South Africa the situation, that is the issue of race, is quite different. That said, “Speaking Back” is not an exhibition tailored to address Cape Town’s distinct historical context: a city whose social, cultural, and civic past is mired in hierarchical classifications of race, but also made vibrant by an organic and effortlessly tolerant multiculturalism that flowered in certain locations, despite prohibitions, and may do so again. As an independent curator marking her return to South Africa from the US with an exhibition at Goodman, Becker is in an excellent position to further explore this territory and its legacy in the future. If she does, a foundation of radical difference could be an exciting place to start.

(1)”Colored” was an official term defined by the South African government between 1950 and 1991 to describe a person of mixed European (“white”) and African (“black”) or Asian ancestry. The term persists among many South Africans, despite its no longer being officially recognized, and carries connotations distinct from those in the US and other English-speaking countries.