“Gallery 3010,” which celebrates the 30th anniversary of Sfeir-Semler Gallery and the 10th anniversary of its Beirut branch, asks what it means to exhibit objects and ideas in a gallery environment, and interrogates the relationship between the gallery and its context. Bringing together artists from different generations, contexts, and sensibilities, the works that spread across the gallery’s industrial space nonetheless share an aesthetic and approach that carry traces of Minimalism and Institutional Critique.

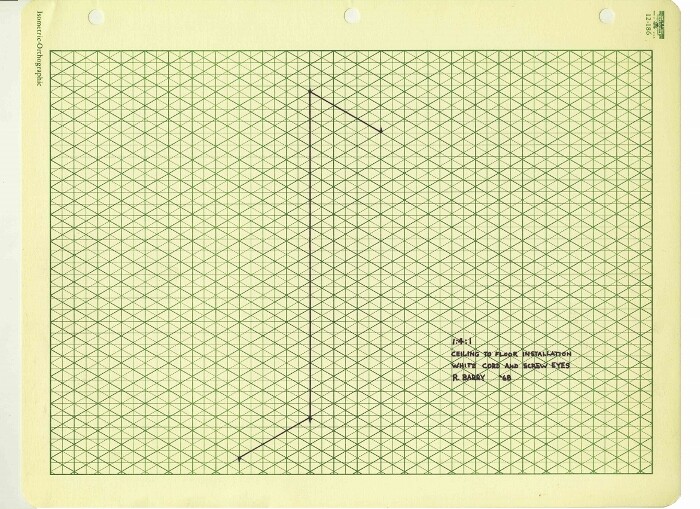

The exhibition is anchored by Robert Barry’s sketch of 1:4:1 (1968)—a white cord extending from the floor to the ceiling with two horizontal sections at each end—which draws attention to the invited artists’ relationship to space. The walls of the gallery serve, both physically and metaphorically, as a surface for artists to play off, and Barry’s notion of presence through invisibility—the thin white line, held in place by a tiny hook, seems barely there—is a common theme in the exhibition, questioning the meaning of making objects now, here, in this context.

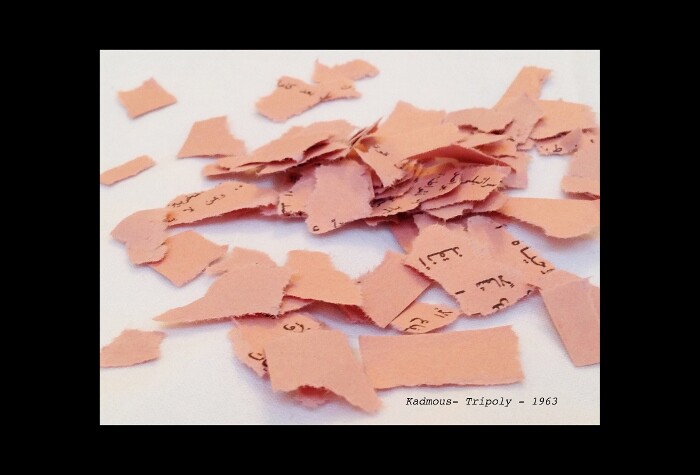

Rabih Mroué’s The Crocodile Who Ate The Sun (2015) consists of a set of 12 framed photographs, presented in a row next to a wall text and, underneath it, a small shelf with leaflets, and the work resonates with an awareness of its own objecthood (though in a different sense from the self-conscious theatricality proposed by Michael Fried). The text, in English, informs visitors that the leaflets are reproductions of an original that “fell from the sky” in 1982, dropped over Lebanon by the Israeli Air Force. The artist presented these leaflets to his friends, and the photographs document their reactions—the leaflets torn, burnt, creased, and crumpled into balls. Mroué thus brings a staged event into the gallery, objectifying an experience that conjures up an earlier one to recognize the problematic nature of commemoration. Every commemorative act excludes another, so is there a more effective way to remember than through the gestures of these individuals? The violence inflicted on the leaflets, monumentalized through the act of photographing and framing them, is appropriate to the politically sterilizing space of the gallery.

Iman Issa’s Material for a sculpture commemorating a blind man who became a great writer, opening up an unparalleled world of possibilities to the people of his nation (2010–2012), a flickering tube monitor atop a flared pedestal, is a monument for our present, dysfuntional times, remembering and commemorating through the absence of an image, aware of its own platform, an object that acknowledges its own representational failure.

Bringing the exhibition full circle, Marwan Rechmaoui’s mural Untitled (2015) addresses the possibility of painting or, rather, mark-making to inspire a greater awareness of the city that the viewer inhabits. An expanded painting composed in concrete, plastic, and paint, the work combines physical materials from Beirut’s urban landscape with a picture of an ominous-looking building. In a changing city (perhaps not so ironically, one of the hippest bars in Beirut is called Under Construction), the act of building is destructive, defeating the two-dimensionality of any purely pictorial representation. Questioning the boundaries, or lack thereof, of the overlapping spaces that we inhabit, Rechmaoui’s large-scale work is an ode to the quotidian reality of the city and the region.

The question emerges: what are the new forms of political labor that can be invented through/against art in the white cube? A gallery’s walls can insulate the space from the world—entombing its guests like the dining room in Luis Buñuel’s The Exterminating Angel. The artists in this show seek to ensure that the wall dividing the gallery from the city remains permeable, that the inside corresponds with the outside.