The past few decades in the art world have seen the emergence of both relational art and “Zombie Formalism.”1 The former is a primarily public funding-dependent, social democratic art, in which the artist is a kind of facilitator, who, because of his or her participation in the contemporary-art game, is adept at following its rules and persuading its audiences of this kind of practice’s criticality. The work itself, however, resembles an educational television program. The artist/teacher instigates a continuous—and perpetually ongoing—debate about a serious issue that is currently popular in the contemporary world. He or she also teaches the audience about the value systems surrounding the issue. It goes without saying that the “issue” usually pertains to a site-specific “history” or “memory.” The artist haphazardly shuffles the histories/memories of indigenous people, makes an installation, and assigns homework: “think for yourself.”

The latter, “Zombie Formalism,” is a corrupted version of alternative modernism. It is ultimately a fetish art, which feeds on the private funds of collectors and investors and repeats clichéd formal qualities of geometric patterns and painterliness. It is an art of gallerists skilled at selling works that follow the rules of contemporary art. In terms of their use of the established formulas of artistic institutions, relational art and Zombie Formalism are two of a kind.

Under these conditions, Gaku Nakano’s first solo show at Kodama Gallery, in Kyoto, especially his installation Listening to a myth told by a goat (2015), displays a typical reaction among artists who are satisfied by neither relational art nor formalism—in other words, those who refuse to make any institutional “relations” (communications, interpretations, functions, etc.) or any substantial “works” (physical objects). We are already familiar with an art form that is non-objective, site-specific, and that occurs here and now, resisting the art market’s easy distribution and merchandising: the happening. Nakano’s installation also starts as a kind of happening or performance, which, however, is not performed, but that rather presents something as having “happened.”

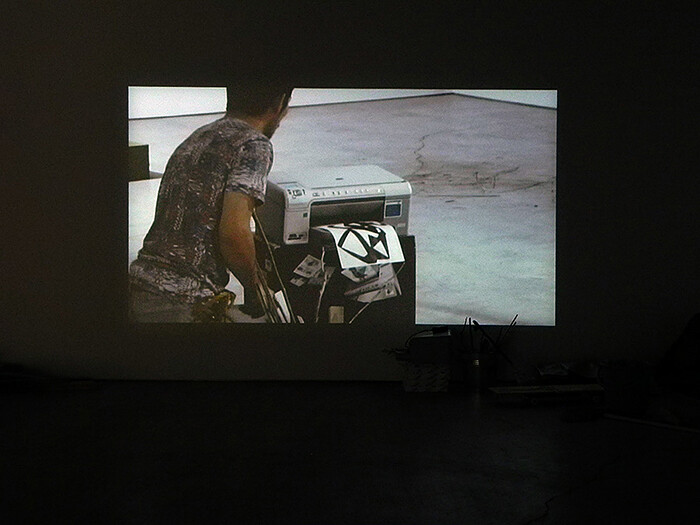

In the week preceding the show, Nakano set up a provisory installation on-site with some objects. He then installed a male goat and continuously transformed the installation as the goat freely moved in the space in reaction to the installed objects as well as the artist’s presence and intervention. Their interplay for three days resulted in a spontaneous but not chance-operated installation, and the entire process is recorded on video. Before the opening the artist cleaned up the space, removed the objects, and effaced any traces (dirt and scratches) of the goat, so that the only remains of this process are two video projections humorously documenting the artist’s solitary play with a goat.2

In his previous works, Nakano also performed a certain action and made its documentary video, as in Ecdysis (2011), in which he recorded the making of a quasi-mold of his own body in wood glue. It is a minor trend among young Japanese artists to show a documentary video of a performance already executed along with some related objects. The whole often looks, in the end, like an egocentric self-satisfaction, for the meaning of the performance is highly personal, unclear, or nonsensical.

Now, devoid of institutional rhetoric and commercial objects, this installation, or rather ex-installation, asserts that it is not an end product in itself but part of an essential generative process. But it is not this popular assertion but Nakano’s installing a goat that frees him from the egocentrism of other artists’ video installations.

The title word, “Mosaic,” has a double meaning: a general meaning and a local, Japanese one. Generally, pieces of a mosaic are united to a certain signification (image, concept). In Japan, where exhibition of male/female genitals is legally prohibited, an image processing to fragment (i.e. obscure) a genital part into unrecognizable squares is called “mosaic.” The “mosaic somehow looks nice” because it reveals and obscures something at the same time, suspending any ultimate interpretation.

An installation is also a mosaic, an interplay of revealing and obscuring. As described above, Nakano formed and transformed his installation in accordance to the goat’s, i.e. the first viewer’s, reactions. The goat/viewer tells a “myth,” a creative and unexpected interpretation, which enacts further transformations. Nakano thus stages a drama of a utopic reception of artwork, which, for him, cannot exist here and now, but only as something “happened,” something gone. Artistic communication is also a myth, and there is always a time lag between the artist and the viewer. Could we call this a drama? A tragedy, maybe, or a goat song.

the_rise_of_zombie_formalism.

This term was aptly coined and made popular by Walter Robinson in “Flipping and the Rise of Zombie Formalism,” Artspace (April 3, 2014), http://www.artspace.com/magazine/contributors/

The debris of the performance is set aside by the gallery wall, but as the remains of the artist’s process rather than as an art object in itself.