The protagonist of Fanny von Reventlow’s novel The Money Complex (1916) suffers from a pathological lack of cash. She is afflicted with a grave sickness of fetishism: money is a being with “whom” she had a very painful relationship that failed dramatically—hence her ailment and impoverishment. In the present times of crisis, the “money complex” no doubt still flourishes, and does so particularly well in the art world, which is host to all kinds of pathologies, promises, and Bohemian myths—chief amongst them the cryptic link between “talent” and success, of being discovered one day, if you only try hard enough. Subtitled “Impoverishment,” the second iteration of Deborah Schamoni’s “Die Marmory Show” departs from such questions of art-world success and its absence—though its itinerary is anything but sociological, or psychoanalytic for that matter. It unfolds within a narrative structure in which “impoverishment” alternates between material, social, or discursive registers. Spreading over the gallery’s two floors, garden, and courtyard, the exhibition that Schamoni co-curated with Nikola Dietrich includes works by Leidy Churchman, Shannon Ebner, Judith Hopf, Tobias Madison, Park McArthur, Manfred Pernice & Martin Städeli, Christoph Schäfer, Eric Sidner, and Peter Wächtler.

Its entry point is Manfred Pernice’s briefkastenOrion (verlorener posten) (2015). Located in the gallery’s courtyard, the work encompasses three plastic chairs, a stool, and a mailbox attached to a metal stand-cum-ashtray, all of which are chained together (a hilarious move in Munich of all places, a wealthy city in which people barely lock their bikes). Inside the mailbox, visitors find a collage-based leaflet consisting of photographs of austere (sub)urban sites, fragments of texts on war, and on modernist architecture and ideology. Because the links between these elements remain somewhat elusive, they trigger all kinds of narratives, both humorous and grave. And this holds not least for the show itself.

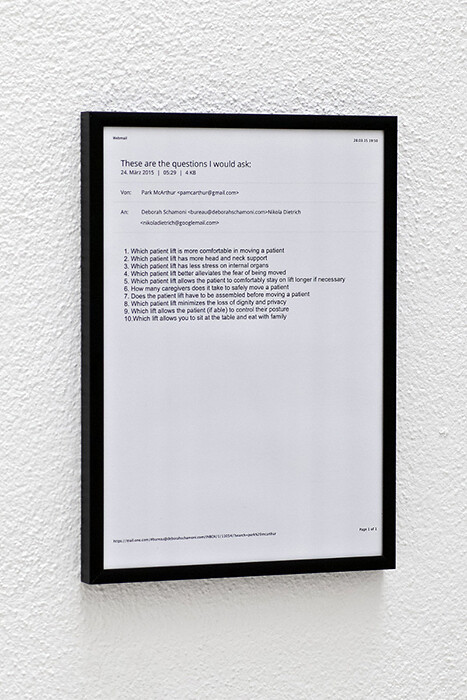

In the first room, Park McArthur’s These are unique questions that I would ask (2015) is on display: a framed email, sent by the artist to the curators, with a deadpan list of ten questions about the suitability of patient lifts (e.g. “8. Which patient lift minimizes the loss of dignity and privacy”). Accessible only by traversing an installation of 6,000 screws dispersed on the marble floor (Flat head Screws, 2013), McArthur’s subtle spatial intervention draws attention to the systemic barriers (of movement) and the institutional politics of inclusion and exclusion that sustain them. In the small exhibition floor above, the drawings of Christoph Schäfer (from the series “Bostanorama,” 2013) feature fantastical, comic-like figures, and objects and words that reference the sites of political struggle during the occupation of Gezi Park in Istanbul. Despite the differences between these practices, impoverishment figures into them both as a discursive effect of power relations in institutional and urban spaces as much as a concern for undoing aesthetic and social hierarchies.

If impoverishment—as Leo Bersani and Ulysse Dutoit have argued1—can function as an aesthetic gesture of denying authority, in the frame of this show it materializes as a practice of upsetting the boundaries between the artistic and its others, loosely echoing Georges Bataille’s notion of the formless as an operation of declassification. Approaching impoverishment via declassification prompts connections between works as different as Shannon Ebner’s concrete-brick sculpture (…) (2010–2015), a kind of concretion of a pixelated (poor) image, displayed in the garden; Eric Sidner’s collages of acephalic paper bodies on cardboard (all Untitled, 2015); and Leidy Churchman’s large-scale vinyl floor painting Untitled (Blood) (2012). Both of these latter works are on view in the second room on the ground floor. While embracing uttermost flatness—painting and floor seem to converge—the horizontal expansion of Churchman’s work into the space and its orientation toward the viewer’s (moving) body simultaneously disassemble and reshape the traditional understanding of painting’s specificity as residing in flatness and opticality.

Dominated by black, yellow, and red shapes, Untitled (Blood) summons the formal sobriety of classical modernist abstraction, opening onto the show’s broader narrative framework: the Armory Show of 1913. “Die Marmory Show II”—a pun on marble (in German, Marmor) as much as on Munich Armory—departs from two historical documents linked to the landmark exhibition that introduced the European avant-garde into the American art discourse and market: a letter by painter Walter Kuhn, one of the co-organizers of the 1913 exhibition (according to the gallery’s press release, the document was discovered between the marble slabs of the gallery floor), and a text by von Reventlow titled “The Like of it Now Happens” (1914), in which the subject of money returns in her critique of the monopolistic selection procedures of the “uncle from America” (Kuhn, presumably)—and here we’ve got the historical coordinates of the show’s focus on impoverishment. While the exhibition would have benefited from engaging more explicitly with impoverishment as a contemporary figure of crisis, it arguably intervenes in a different terrain: that of the (art-historical) function of the document that the curators appropriate willfully and idiosyncratically. The authenticity of the records “Marmory Show II” draws upon has indeed been questioned ever since they appeared, but their truthfulness (or fictionality) might be actually what is least interesting about them. They perform the job of triggering an open-ended, expandable, and collectively produced narrative. And at this the show succeeds.

Leo Bersani and Ulysse Dutoit, Arts of Impoverishment. Beckett, Rothko, Resnais (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1993).