I flew in on May 12, on one of the first charter flights direct from New York to Havana. We landed, and the stewardess happily announced: “Ladies and gentlemen, welcome to Miami.” After some hesitant laughter from the passengers, she genuinely apologized and added: “I’m so sorry, I meant to say ‘welcome to Havana.’” I wondered if there was some premonition in her slip, if Cuba was going to face a process of Floridation, and the known role of Miami as Little Havana was to be revenged with a Cuban Little Miami. The options of the reactions to the threat of exchange of roles might be surrender, enlightened negotiation to maintain a balance between ideology (idealism) and an understandably longed-for tsunami of consumerism, or a hardening of the old guard that still is in office. Discussing these points with Cuban friends while speculating about a relatively distant future, they unanimously picked “enlightened negotiation” as the most likely course of action.

This was the context in which Tania Bruguera decided to restage her performance of Tatlin’s Whisper #6 (2009) on Havana’s Plaza de la Revolución and was prohibited from doing so. The only credible argument for the prohibition now (that I picked up from friends in the know) was that positioning an open mic in such a place, giving anyone a minute to say whatever one wanted, as the work dictates, carried the possibility of polarizing people to the point of creating a violent and uncontrollable melee. Alternative locations and conditions for Tatlin were proposed, each of which was found to be unacceptable, either by art officials or by the artist herself. Because the first staging of the performance piece, Tatlin’s Whisper # 6 (Havana Version), on March 29, 2009 as part of the 10th Havana Bienal, had ignited a dramatic conflict with the authorities, the inflexibility of the bureaucrats on the present occasion was predictable. Following tense discussions and with her intention to go ahead with the performance anyway, Tania ended up under temporary arrest three consecutive days, from December 30, 2014 to January 1, 2015. Her passport was taken from her and kept unless and until she agreed to leave Cuba and not return. Tania insisted on her rights as a Cuban and firmly refused the offer; since then, she has stayed in what may be termed “city arrest” as opposed to house arrest. Everyone connected with the arts, including people unsympathetic to Tania’s project, believed the authorities would avoid escalating the confrontation and return her passport by the time the Havana Bienal opened on May 22.

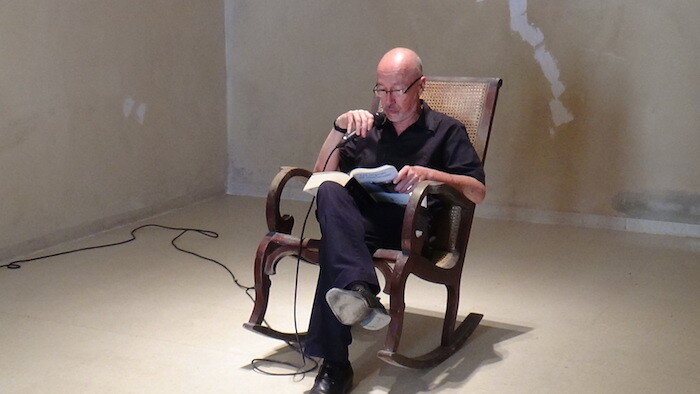

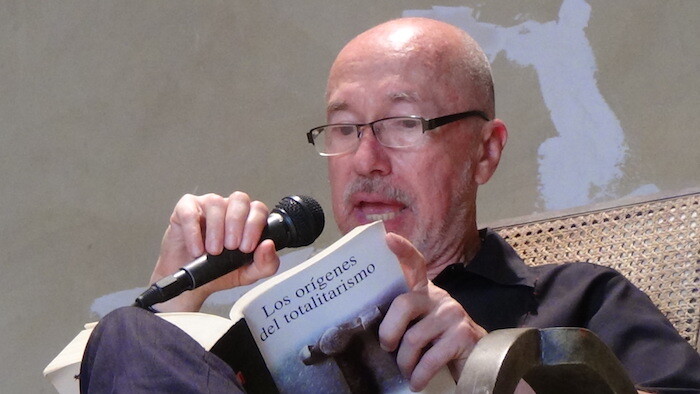

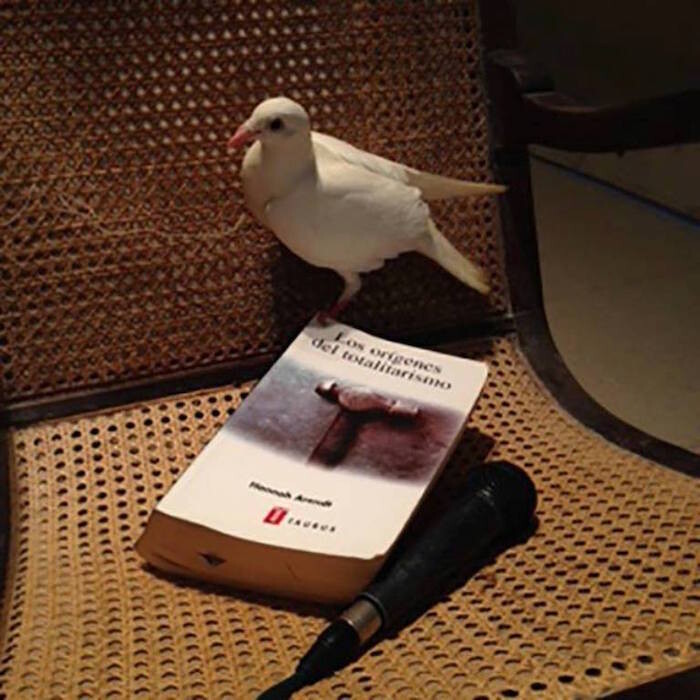

In the ensuing weeks, Tania did not sit idle but initiated a series of events consistent with her interest in pedagogical activities. First, she organized a workshop open to all to study the Cuban penal code, focusing in particular on the provisions invoked to punish her. In performance mode, she started the Hannah Arendt International Institute for Artivism on May 20, two days before the opening of the biennial and coinciding with the 113th anniversary of Cuban Independence Day, obeying to the letter all of the government requirements for opening a private enterprise. On March 9, she had received a certificate of cuentapropista (a permission to work on her own private initiative) as a teacher. Using a room on the ground floor of her family home in Old Havana that she was able to transform into a storefront, she started a 100-hour-long reading of Hannah Arendt’s The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951) in Spanish as a teaching activity, taking turns reading with friends. The readers were inside, but their voices were directed to the street with a loudspeaker so as to be overheard by people passing by. The power of the piece wasn’t derived from the content of the text, but rather from the choice of book, the setting, and the concentrated endurance of those involved in the marathon. I attended the reading half an hour after it began and was moved.

The streets surrounding Tania’s block had been under construction for weeks, as the roads were being dug up for electrical-wiring repair. In a tactical move that the authorities must have thought clever and deniable, workers were instructed to move noisy equipment in front of Tania’s house. Later I learned that a few hours after I left, they started drilling in the street. I was told that some of Tania’s neighbors claim the workers ended up re-digging sections of the street that they had already repaired.

The Arendt performance in itself is probably one of the most elegant and powerful of Tania’s works. She presented a situation that on its surface was totally harmless. She only used her private space, precisely stopping at the borderline of where public space starts. The reading was not louder than any music coming out of a window that one might normally hear on the street. And yet, a philosophical text, difficult to hear, and probably exceeding anyone’s conceivable attention span under the circumstances, was considered to be sufficiently threatening to the government (or at least some of its officials) that steps were taken to interfere with the performance. What they didn’t understand is that drilling made no difference. With or without the drilling noise, the piece was untouchable. Tania had identified a crack in the wall of official regulations and the authorities revealed themselves as one step short of the moral equivalent of book burners. If this were a chess game, Tania had achieved a “check.”

Tania’s harassment continues. The current Havana Bienal, now in its 12th iteration, has several goals. Since the late nineties, the tendency had been to perform a service for art tourism, which, among other things, supported a market for Cuban artists. This year, however, a shift toward a focused curatorial vision that emphasizes urban communities is apparent. This shift of concept is not easy, for there’s an unwillingness to undermine the market; finding a balance will take some time to achieve. The biennial this year was also used as an opportunity to gather artists from the Cuban diaspora. Reflecting these concerns, in a parallel activity independent from the biennial, the Museum of Fine Arts organized shows by Tomás Sánchez, Alexandre Arrechea, and Gustavo Pérez Monzón.

Tomás Sánchez has been an iconic figure in Cuba for many decades because, while conservative in his aesthetics, he has consistently joined in with younger art rebels. Sánchez personally invited Tania to come to his opening on May 23, but in an incomprehensible move (at the time of this writing, I haven’t yet come across any official explanation), Tania was denied access to the museum and was therefore unable to attend. Without premeditation on Tania’s part, this became yet another performance piece.

Tania is, in fact, the artist who acts most consistently and visibly as a nexus between Cuban artists working outside Cuba and those working inside. Her Memoria de la Postguerra, a publication she started in 1993, in which she assembled contributions from both insiders and outsiders, served as a bridge. Her Cátedra Arte de Conducta [Behavior Art Department] (2002–2009), an art school with foreign guests as instructors, was extremely influential in breaking down Cuban cultural isolation. Nevertheless, in this current mission and in the context of this biennial, she is not only ostracized, but also harassed in an unacceptable way. As it happened, I left Havana on May 21, so I was not in a position to witness either the opening of the biennial, the incidents at the Museum of Fine Arts, or the conclusion of her reading of Arendt and subsequent short arrest on May 24. Whatever questions I had about Tania’s opening moves, as art and as politics (and had a chance to discuss with her as a friend), they are now irrelevant to the issues raised by the reckless performance of the authorities in this sorry series of episodes. There was a time when it seemed possible, to me at least, that the utopian convictions of many in the cultural elite of Cuba would be strong enough to counteract political bureaucracy. Tania has shown us that it’s not. In this game of chess, she scored a strong second check, maybe even a checkmate.