May 9–November 22, 2015

When Kenya announced the artist list for their pavilion for this year’s Venice Biennale, forefronted for the second time in a row by Italian hotelier Armando Tanzini, alongside an astounding nine foreign participants and only one Kenyan, the only appropriate response—as far as I was concerned—would have been something akin to Lee Lozano throwing issues of Artforum into the air, as in her 1969 Throw-Up Piece. Disillusioned by the collusions between art and commerce, and repulsed by those who participated in its occurrence, Lozano’s gesture marked a breaking point. It was a final attempt to ask what, exactly, we—participants in the production of artistic value, which too often comes down to nothing but cultural entrepreneurship—are doing here?

Although copies of Artforum were not thrown around (nor Biennale guides, for that matter), when the Kenyan cultural ministry officials responded to the appointed curators of the Pavilion by calling them “imposters” and formally disassociating themselves from the presentation, a similar point of no return had been reached. The effect was immediate: not only did it mark a critique of the organizing party for having so blatantly neglected to represent their own, but also of the Biennale, which failed in its responsibilities by enabling such lapses of morality and representation. The Kenyan Pavilion was notably withdrawn from the official Biennale selection, echoing—in stark protest—Lozano’s parting words to the art world: “I have decided what I don’t want and am moving away from it, towards (o joy!) the unknown! (Thrill of all thrills.)”1

Though Lozano’s statements never received an appropriate response, and her work is somewhat obviously absent from the Biennale, the parallel between her actions and those of the Kenyan Pavilion bring to question the notion of withdrawal as a political or social act of resistance. Whether rooted in a “real-life” situation or appropriated as an artistic strategy, acts of withdrawal—exit, general strike—can be game-changing, or at least a way to flip the board. In this sense, withdrawal should be read as an active gesture—a critical expression, which subsists not as denial, but as an affirmation of the monopolizing centers of power that largely determine cultural production and dissemination. Kenya’s dropping out, as well as Costa Rica’s, for that matter (resulting from internal financial conflicts and scandal), is a clear attestation of the structural problems which pervade the Biennale, existing insidiously within its walls, and blocking any clearly demarcated exit points—which, by the way, in the maze of the Biennale, are hard to find—will continue without interruption.

Nevertheless, this becomes particularly interesting when one considers the artists featured within the framework of “All the World’s Futures,” Okwui Enwezor’s curatorial project, who employ withdrawal as a symbolic or critical component of their work. The Biennale, without doubt, is a hegemonic power in itself, and by accepting its invitation to participate, one is also occupying a privileged position: a proximity to those responsible for executing decisions that effect its framework, and at that, a position that enables a direct, internal critique.

The Swiss Pavilion, in choosing Pamela Rosenkranz as its representative, is a prime example of the potentials of this position. Rosenkranz’s project, Our Product (2015), is an absorbing installation comprised of an enticing pool of Pepto Bismol-colored liquid—a fleshy, pink pigment flooding the floor of the pavilion—accompanied by a strangely sweet smell of talcum powder or baby wipes. The pavilion’s foyer is saturated with an artificial mint-green light, spilling out over an austere and unkempt garden. Emptied of a so-called core materiality, the work withdraws into a realm of pure sense, mirroring the way that both art and commerce utilize “empty” faculties, like color, scent, or sound to stimulate our interest as consumers, a topic furthered by Kevin McGarry in his review of the Biennale on May 7. By emphasizing the alluring element often present in marketing strategies—a recurrent gesture in Rosenkranz’s practice—the artist also protects herself from participation in it, warning, perhaps, of falling prey to similar forces within the current context.

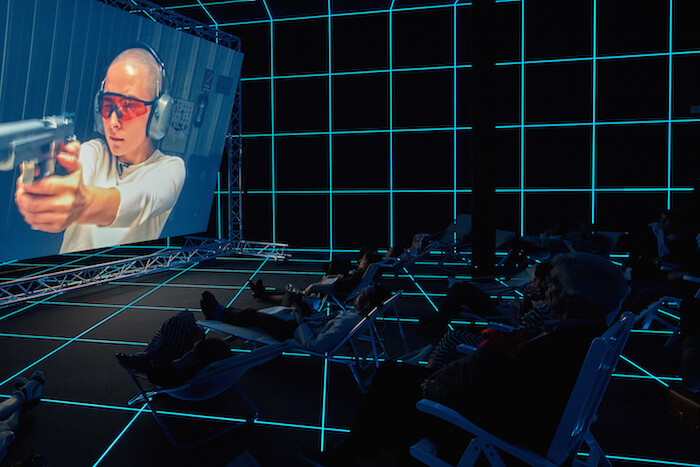

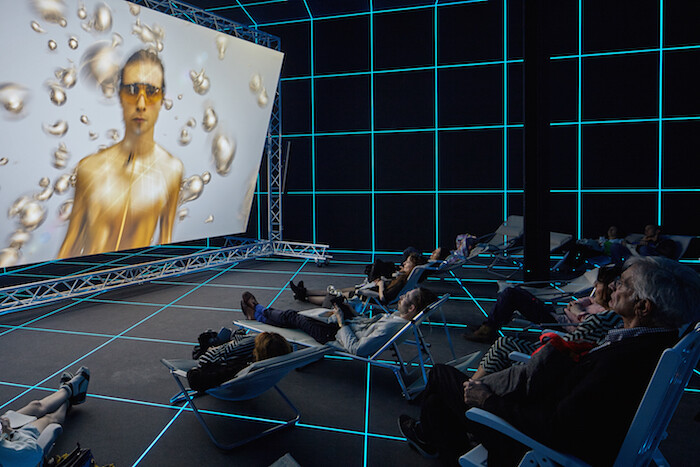

At the German Pavilion, Olaf Nicolai, Hito Steyerl, Tobias Zielony, and duo Jasmina Metwaly & Philip Rizk have created Fabrik, a four-part “factory” purported to be an examination of how the circulation of images has an effect on reality and political representation. Hito Steyerl’s work, The Factory of the Sun (2015) is, for example, a video projected in what is dubbed the “Motion Capture Studio”—a theater room mapped with an immersive 3D matrix where viewers can watch the video while lounging on plastic sun loungers. Narrated by a soft-spoken female voice, it consists of a game that progresses by virtue of light impulses overlaying disco tunes, staged cable-news segments, and the movements made by virtual protagonists clad in gold lamé, motion-capture-device-adorned unitards. Steyerl conveys this heliocentricity, the vitalistic relationship with light, as somewhat of a bright-eyed metaphor for progress, but only insofar as it becomes a way to discuss our complicity with the sun (as a progenitor of life, and thereby capital). By entering the virtual, she negotiates the potentials of our digital present—as part accelerated advertisement, part escapism—in order to reassess the current relationship between pictorial and political representation.

Similarly, Olaf Nicolai’s work Giro (2015) brings Steyerl’s inquiries into the real by placing three unseen or unheard actors to live on the roof of the pavilion for the duration of the Biennale. Under the Venice sun, the participants will allegedly appear at the edges of the building to sporadically cast boomerangs in any given direction, though I saw neither actors nor boomerangs. Whilst the motives of this project are never fully disclosed—an appropriate strategy in any covert operation—Nicolai’s work is a reclusion from the material excess of the Biennale, and a dramatization of the economic and symbolic feedback loops that perpetuate its existence.

Though a common denominator of Rosenkranz, Steyerl, and Nicolai’s work is the disclosure of variable power structures, they also operate through a first-person point of view, in which affect defines a part of the experience. In this vein, projects such as They Come to Us without a Word (2015), Joan Jonas’s sentimental project at the United States Pavilion, a bizarre installation of drawings and multiple videos of bees and fish, could be seen as equally hermetic. The Pavilion has been re-imagined as an almost Cremaster-esque space, if only Cremaster had been produced with a delicate, feminine touch—decorated as it is by lengths of beads suspended from chandeliers, rippled Murano glass mirrors, ambient lighting, and a soundtrack featuring songs by Sami musician Ánde Somby and Jonas’s frequent collaborator Jason Moran. Equally affective and undemanding of its viewer is the Tuvalu Pavilion, in which artist and curator Vincent J.F. Huang has created a moment of poetic distance as viewers walk over a rickety bridge hovering over a steaming, shallow pool. Uncomplicated and non-indulgent, Huang’s installation is a quiet and humble moment in stark contrast to the rest of the Arsenale, or the entire Biennale for that matter.

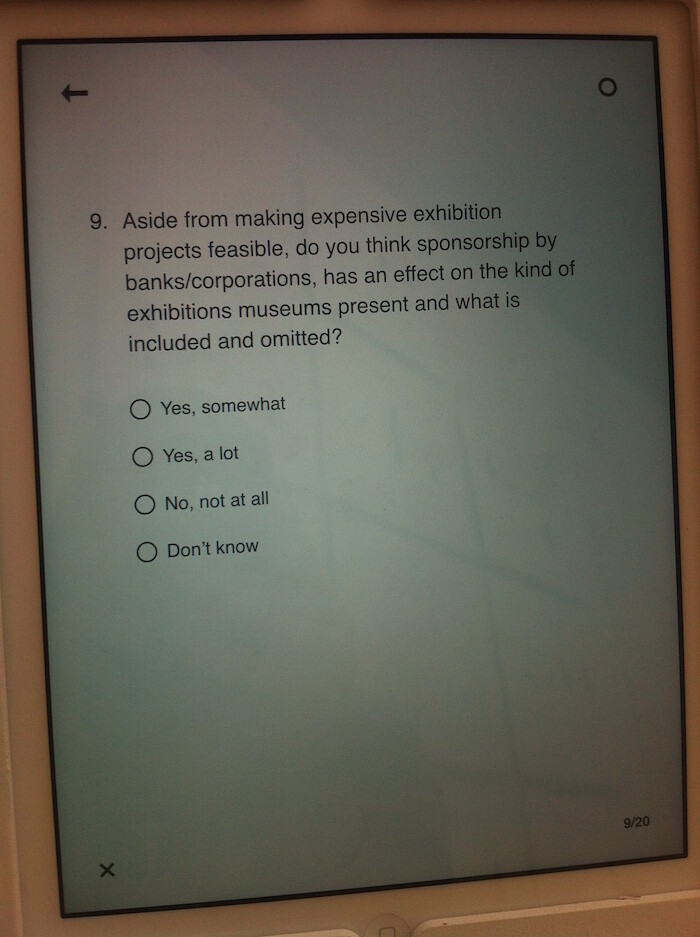

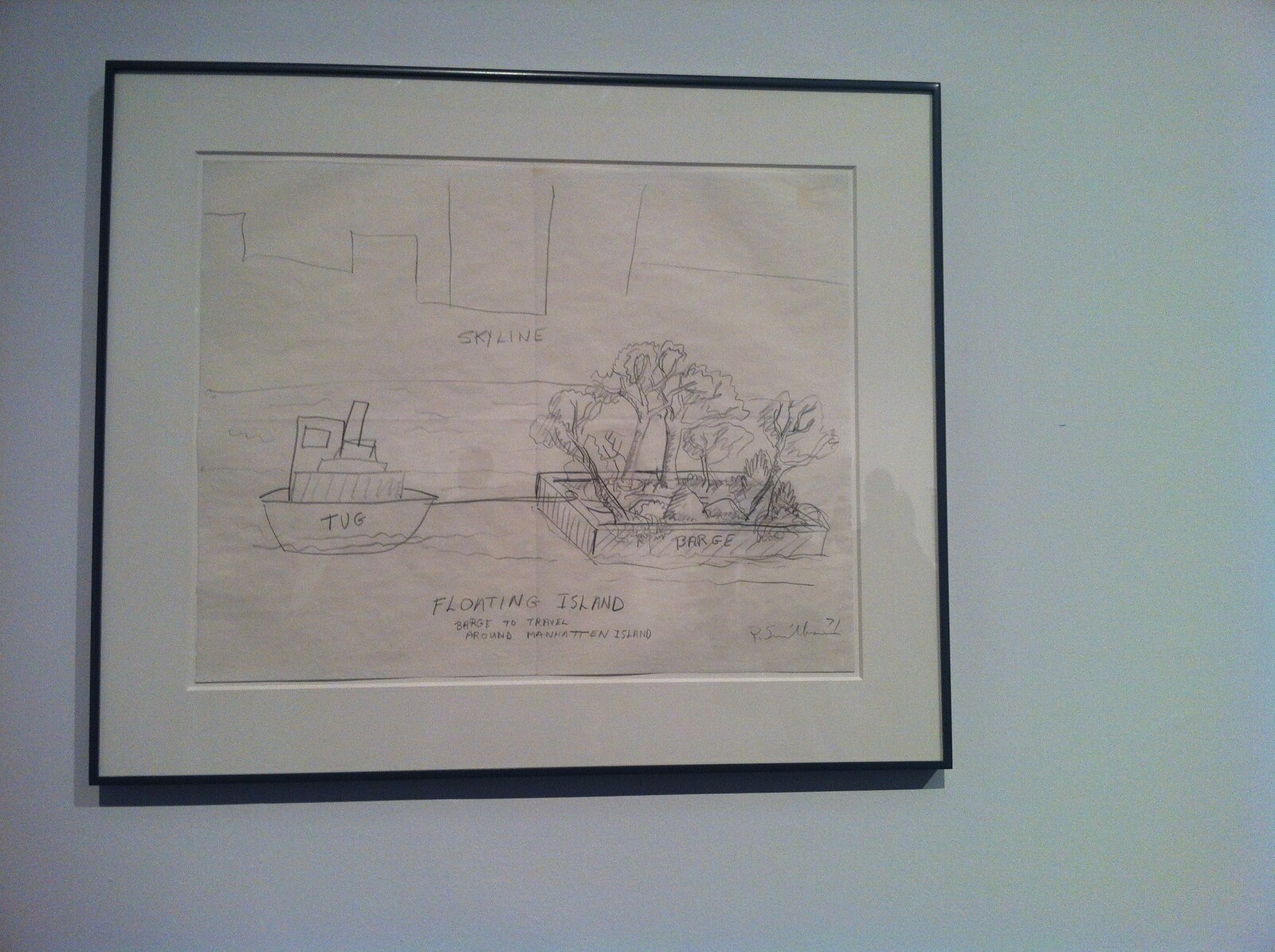

Within Enwezor’s exhibition, similar moments were far and wide, seen only in individual cases: strolling through Isa Genzken’s architectural models, for example; or filling out Hans Haacke’s 20-question survey World Poll (2015); staring into Robert Smithson’s utopian designs, Floating Island - Barge to Travel Around Manhattan Island (1971); or even simply exiting the show, by passing under Jeremy Deller’s inexhaustibly ironic 2013 banner Hello, today you have the day off… If only. All of these instances, however, merely deflect from the overall chaos and unbalance of the exhibition, and have little impact on one’s total experience.

At that, despite the few pavilions that took into consideration the possibility of an alternative production of meaning even within the Biennale’s borders, Enwezor’s exhibition is a sordid reminder of our inevitable entrapment. It seems ironic, really, that a project aiming to consider our futurity in an “age of anxieties” would present no alternatives, no future, no escape. The confusing and flurried show seems more a self-fulfilling prophecy, a recirculation of a distressed history. Walking around, Lozano’s calculated abandonment of the art world seems easy to understand. Though the thrill of the unknown she searched for in her departure is readily available—at least in those participating whom have found ways to withdraw into autonomy—it is lost within Enwezor’s bleak and backward-looking exhibition. Perhaps certain places of power, to somewhat inaccurately paraphrase Michel de Certeau’s The Practice of Everyday Life (1984), are simply condemned to inertia.

Lucy R. Lippard “Cerebellion and Cosmic Storms,” in Lee Lozano, ed. Iris Müller-Westermann. (Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz, 2010), 192.