May 9–November 22, 2015

A 2015 exhibition titled “All the World’s Futures” is more likely than not to be bleak (in tone). Earth, in curator Okwui Enwezor’s curatorial statement, is “shattered and in disarray, scarred by violent turmoil, panicked by specters of economic crisis (…) Everywhere one turns new crisis, uncertainty, and deepening insecurity across all regions of the world seem to leap into view.” So the 56th Venice Biennale does not purport to be a catalog of hopeful ways out. Enwezor is quick to acknowledge that the grandiosity of what the institution of the Biennale has evolved into speaks to “the unquestionable allure of this most anachronistic of exhibition models dedicated to national representation.” And while Venice is the most expansive international exhibition in the world of contemporary art, this year it is dwarfed by an analogously outmoded, nation-obsessed spectacle taking place only two hours west: Expo Milano 2015.

This pop-up city on the steroidal scale of twenty-first-century Chinese urbanization, located on the periphery of Milan, where some countries’ pavilions are the size of four-floor department stores—most of whose architectures are garishly ill-conceived—is born of the theme “Feeding the Planet, Energy for Life.” It’s all about food, its culinary varieties and geopolitical complexities. Case in point: the pavilion sandwiched between Turkmenistan and Qatar, no joke, belongs to McDonald’s (though the gargantuan arcades of Eataly are somehow more disturbing to see alongside nations with traditional citizenries).

Consumption is in the air, from the Expo to the sublime new Fondazione Prada, which opens this week in Milan as well (which, though it is a gift to humanity, is a temple built by luxury shopping); to the bonkers survey of art at la Triennale in Milan, “Art & Foods. Rituals since 1851,” curated by Germano Celant and containing food and products designed for its making, storage, and presentation; to the yachts docked outside the Giardini; to the most cogent of the “filters” through which Enwezor casts his Biennale: capital. He rightly calls capital “the great drama of our age,” and as one of the most publicized gestures of the exhibition, he has organized regular readings of Karl Marx’s Das Kapital (1867) to occur in the “arena”—a theater inside the Giardini’s Central Pavilion, where live acts are scheduled to take place throughout the summer.

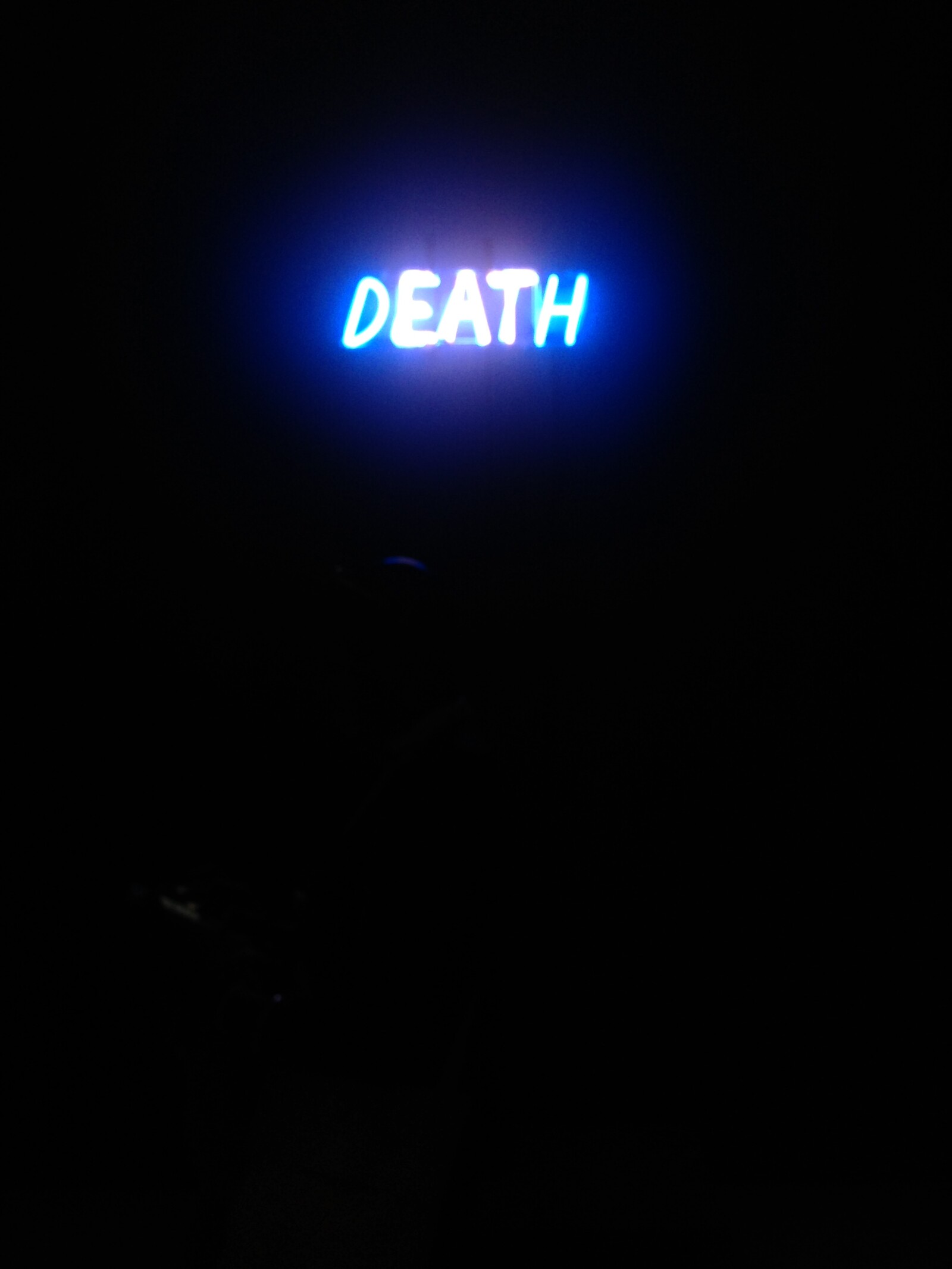

Entering the international exhibition by following an empty, gunmetal-grey antechamber, visitors to the Arsenale step into a dark room of knives by Adel Abdessemed and equally violent neon text by Bruce Nauman. The most minimal sign amalgamates the words EAT and DEATH, which I encountered as a convenient logo for the line of thinking kindled by my brush with Expo’s Disney-fied delirium. To consume too much or too little brings death. Sustenance is a balancing act, which as a human race we are clearly failing at spectacularly. By now it is a given that any significant biennial will take on dimensions of this collapse on as a focus.

Foraging in the Corderie of the Arsenale and the Central Pavilion of the Giardini for inspirational nourishment is rough. Probably the most memorable moment in the former location is when one rounds a corner into a towering womb faceted with eight titanic paintings from 2014 by Georg Baselitz, each containing a ghoulish, inverted pope on a black canvas and a different title, but essentially an edition of eight. It’s hard to suppress the thought that there are dealers who would kill each other to have these in their booth at a fair. In the Giardini, there is another room of serial memento moris by another revered European painter, Marlene Dumas, whose petite skulls—“Skull” (2013–2015)—travel through much more formal variety and emotion, comprising a deathly little journey.

Even if the Baselitz work is abominable, a shock is a good reminder of life. A bad one, more an illustration of a once vital force wasting away, is Adrian Piper’s new performance, where three women at corporate-looking reception desks encourage guests to sign a contract on an iPad that binds them to statements like “I will always be too expensive to buy,” also written on the wall in gold. That is pathos. Included in the Hans Haacke room in the Giardini is his 1970 “MoMA Poll” and other new works that also involve iPads. It’s by no means a disaster, but there is some safety in the ubiquitous relevance of his work. Notable about this selection is Blue Sail (1964–65), the blue chiffon panel draped in the middle of the room, surrounded by stats and charts, which, blown around from below by an oscillating fan, imitates a serenely churning sea. The sea, just as scary as popes and skeletons, is typically a more moving symbol of mortality, and it figures prominently into two of the overall best works in the show, which are recent films by John Akomfrah, Vertigo Sea (2015), and Steve McQueen, Ashes (2014) (though these moving-image works are somewhat annexed from the main storyline, tucked behind their sound curtains).

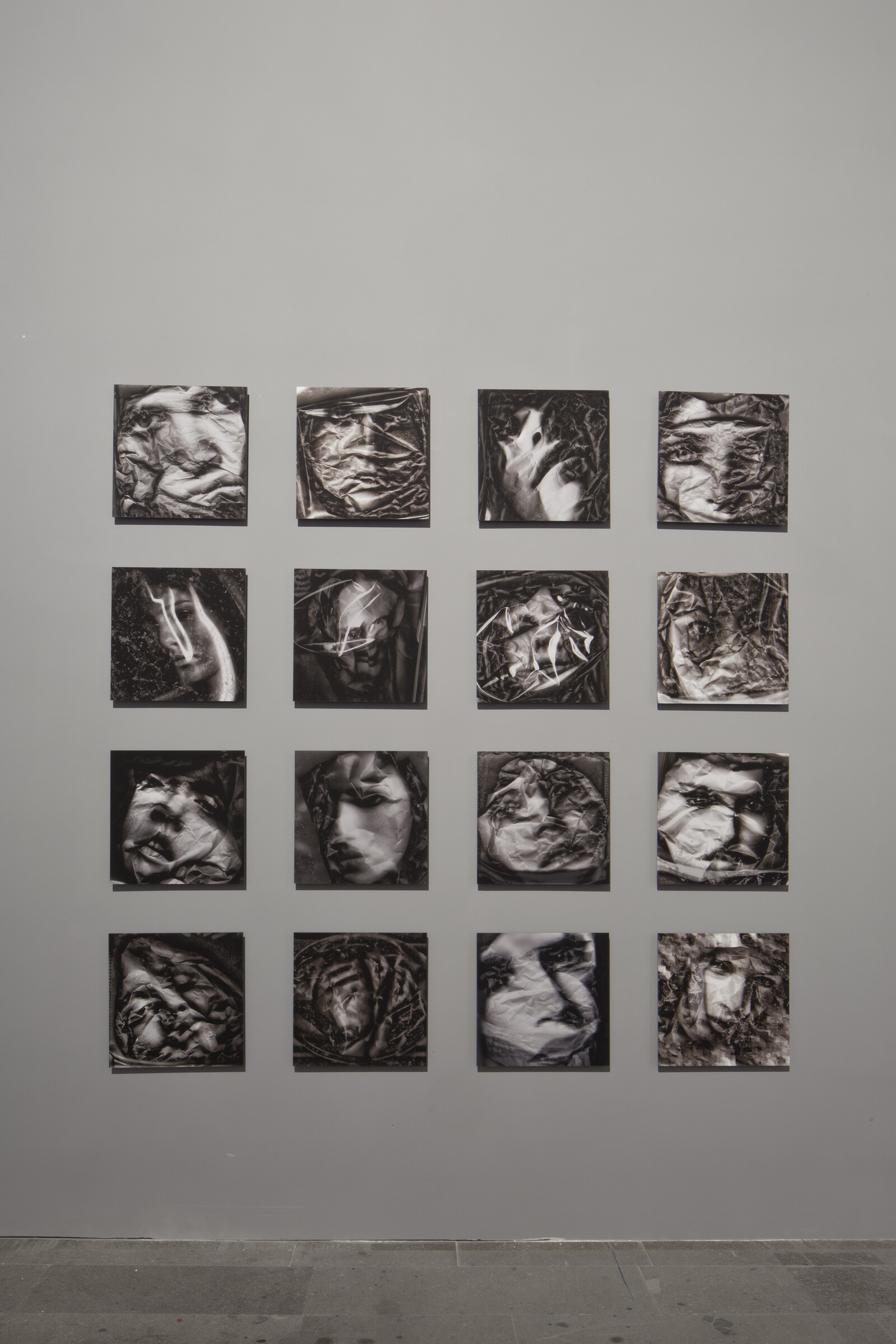

The problem with Haacke here is that in such a mammoth show with so few surprises, adding loads of content from a twentieth-century master can be counter-productive. Even more voluminous is the gridded presentation of Harun Farocki’s entire filmography as a singular archive (which emphasizes, via snowy screens, those films which have not yet been digitized and risk being lost to time). To a lesser extent, Chris Marker is similarly situated, represented by multiple works, including a massive photo installation made in 2012, the last year of his life: Passengers, a registry of hundreds of strangers shot on the Paris metro.

The fact that there are so few artists here, from either the present or history, combined with the practical challenges that the Arsenale always presents, the exhibition’s layout forces viewers to weave left and right interminably instead of charging down the tunnel, making the space into a maze where one’s attention drifts away from what is on view and instead toward anxiously looking for what’s missing here. Less than a tenth of the artists in the show were born after 1980. One is Algeria-based Massinissa Selmani, who showed oneiric works on paper, all 2015. In these spare graphite drawings, he records quotidian scenes which, on closer inspection, appear to be assemblages of events and places floating together on a blank page. Each one contains discrete elements of color: a blue dog facing the wall of a militarized border; a man with a red handcart containing, in an absurd juxtaposition of scale, an airplane, buttressed by scenes of violence and selfie-taking; two apparent dignitaries on a tarmac joined by a green ribbon they hold in their hands.

Curiously, two other bodies of work that stand out are also suites of pencil drawings. Joachim Schönfeldt’s “Factory Drawings Drawn in Situ” (2010—2015) treat machinery, men at work, and men at rest as subjects that are one and the same by drawing them all in a dispassionate style that appears both technical and observational. Much more singularly affecting are Olga Chernysheva’s 2015 “Untitled (Escalations 1-5)” drawing series of things plucked from the collective unconscious of cold, Soviet desperation—bread and factories—especially five pieces that picture faceless lines of civilians in heavy winter coats stretching endlessly into vanishing points. Like in Selmani’s compositions, Chernysheva’s figures are adrift in a void where lack of agency is visually manifested as spatial ambiguity.

A handful of transcendent works on paper isn’t a great reward for those who travel all the way to Venice. The institution’s capability for presenting huge statements feels as if it has misfired this year, or at least missed its targets. There is Katharina Grosse’s show-stopping hall of rainbow rubble in the Arsenale, perfectly executed for the space, although the exact reason why it might be an anchor for this show is not entirely legible.

In the Giardini, Thomas Hirschhorn has wedged a vertiginous installation into a relatively compact room. Titled Roof Off (2015), a tempest of papers, torn HVAC piping, drywall, and other structural detritus rains down from above. Peering up through the wreckage the sun is blinding; only, there is no sun. There are lights, and, despite the title, the roof is on—it’s a false sky. Of all exalted exhibition places in the world, in the Giardini the gestural opening up of spaces, the doing of splendid architectural interventions and whatnot, is a long-running trend. I’d like to think that Hirschhorn’s piece winks at this, and more generally at how the Biennale is consumed and exhausted by its audiences.