Behind every balance is a hidden tension—a negotiation between opposed bodies that equalizes their forces in order to form stability. There is, however, a permanent risk of falling, and imbalance occurs when one side shifts forces and disturbs the distribution of weight. Behind any image of equilibrium, one can glimpse fragility. Balanced structures generate systems of correspondence where the strength in tension contains conflict and mess.

To mark a decade of collaboration between the gallery and the artist, Travesía Cuatro exhibits the most recent works of José Dávila in what could be two shows in one, since what is on view corresponds to two very different series of the artist’s work. In the first room is a group of sculptures that seems to adhere more closely to the title of the show—“Actos tectónicos de duda y deseo” [Tectonic Acts of Doubt and Desire]: three pieces—and an additional one placed in the courtyard of the gallery—each titled Joint Effort (all 2015) made out of glass, boulders, and ratchet straps. For each work, the artist positioned a different kind of glass—mirrored, transparent, and tinted—next to a stone, using garishly colored commercial tie-down straps to contain the tension between these discrete objects.

The sculptures appear to be in a precarious balance, like gestures caught between an imminent destruction and permanence. The structure is thereby active: a permanent performative interdependence of things. Dávila constantly quotes, re-appropriates, and reinterprets works of art history; in these sculptures, he condenses the coldness and precision of minimalism with the raw materials of Arte Povera and the anti-rationalist imperatives of Neo-Concretism. References to Barnett Newman also make an appearance—not only in the straps that are powerfully reminiscent of his paintings, but also in the way these sculptures seem to deal with the concept of the sublime put forward by the American artist. If it’s generally accepted that the sublime responds to a greatness that lies beyond calculation, measurement, or imitation, in “Actos tectónicos de duda y deseo,” the various elements that make up Dávila’s sculptures deal with the sublime by keeping everything on the verge of collapse. If, in some of his previous works, the artist seemed to show the failure of functional modernist architectural principles, these new sculptures stress the triumph of empirical knowledge over modern positivist design. In their hazardous balance, it is the stubbornness of matter that imposes its rhythm and determines the form.

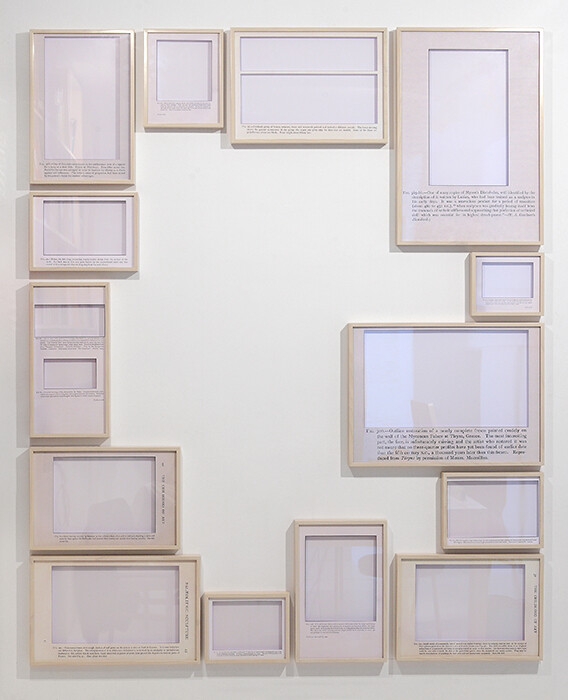

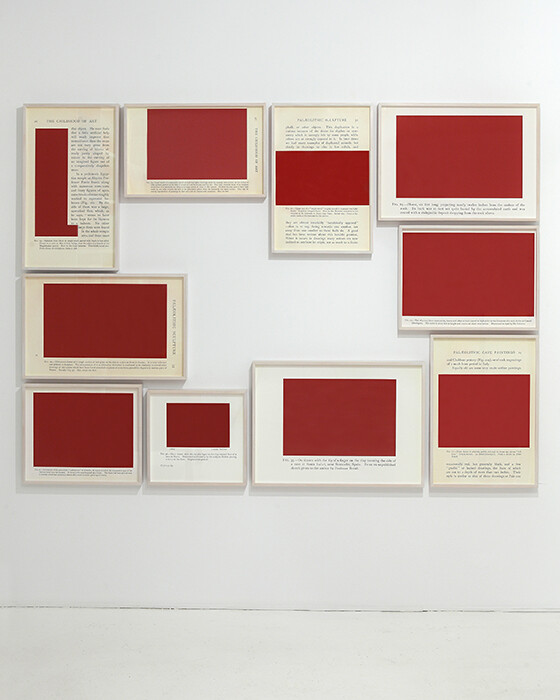

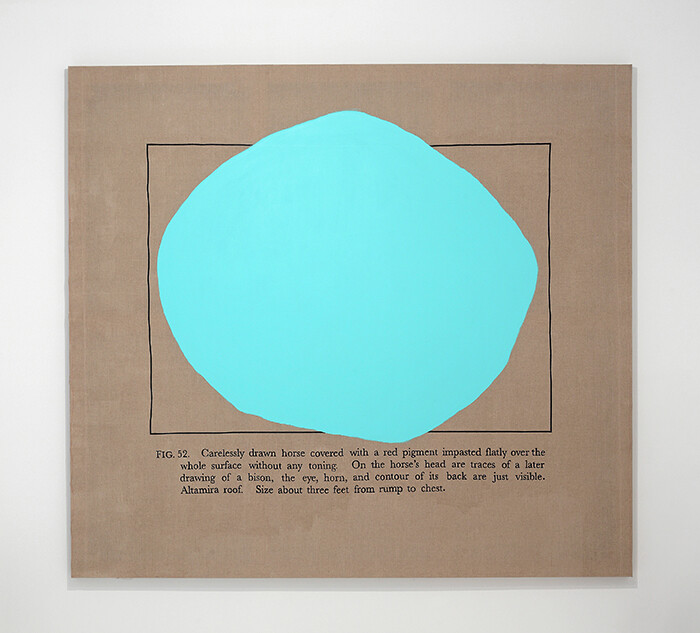

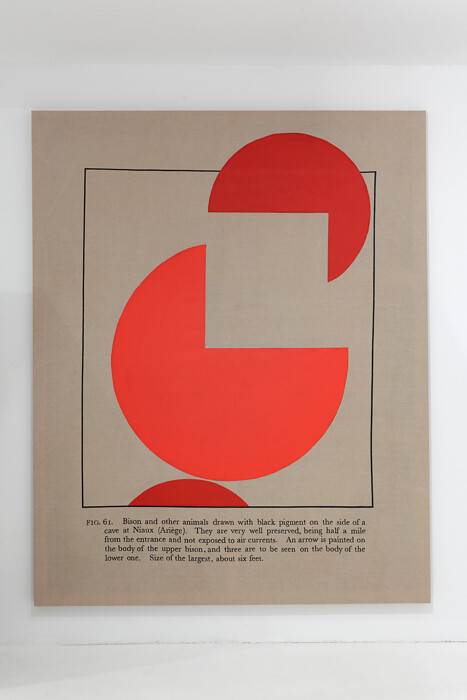

The inner rooms of the gallery display The Origins of Drawing and The Origins of Drawing IV (both 2014), two groups of reproductions of pages from the book The Childhood of Art or The Ascent of Man, published in 1912 by author H. G. Spearing, which presents a profusion of illustrations on the evolution of art. Dávila has removed the pictures from these pages and left only the captions with the images’ outlines, the inside of which is left white in some cases, painted in red in others. The arrangement of these works on the gallery wall composes a frame in whose interior there is another empty space. The set offers the viewer a poetic specificity that surpasses the expressive power of the words I am now writing. The carefully composed captions possess a powerful, evocative language that suggests a universe of images. Some are written from the safe distance of scientific, almost clinical, discourse, as in “FIG. 24. —Horse, six feet long, projecting nearly twelve inches from the surface of the rock. Its back was at first not quite buried by the accumulated earth and was coated with a stalagmitic deposit dropping from the rock above.” While in others, my favorite ones, the narrator exceeds his forensic language and adopts a speculative tone, as in “FIG. 318. —One of four fishermen drawn on the earthenware stein of a support for a lamp or a fruit dish. Found at Phylakopi. Four fifths actual size. Probably the eye was enlarged in order to increase its efficacy as a charm against evil influence. The artist’s sense of proportion had been ruined by his patron’s desire for material advantages.”

If my body was tense in the first part of the exhibition, in this part of the show it became relaxed. Employing two very different strategies, the artist responds to the hegemonic narratives of modernity that privilege scientific reason over experience, and whose logic is based on notions of progress and evolution. In the case of Spearing’s encyclopaedia, it seems that Dávila frees the drawn elements from the grip of positivism and, in doing so, activates the potential of the lethargic imagination.

By a twist of fate, coinciding with Jose Dávila’s exhibition, the Museo Reina Sofía, also in Madrid, is devoting a retrospective to Mathias Goeritz, the German artist—Mexican by adoption—who formulated the concept of “emotional architecture,” and who, between 1949 and 1952, taught architecture in Guadalajara, Dávila’s hometown. Visiting Goeritz’s show, it becomes clear how his ideas of emotional geometry and its use of a minimalist aesthetic to produce a quasi-mythical, sensorial perception of space are present in Dávila’s proposal. If Goeritz sought an “emotional architecture” as an oppositional force to functionalism in architecture, Dávila looks to tectonic structures that play with light, space, and raw materials to poetical ends.