There is a clear spatial hierarchy at art fairs: modern and old master works on one side, contemporary on another. But this year’s SP-Arte, in its 11th iteration, inaugurated a new section called “Open Plan,” installing the most ambitious and large-scale works on the third floor of Oscar Niemeyer’s Bienal pavilion, a space usually left empty. High above, hanging over the curvy ramps of the modernist building, is a makeshift bridge, a fragile structure of wood and strings built by artist Rochelle Costi (Residência – escada, 2010/15, presented by Luciana Brito, São Paulo; Celma Albuquerque, Belo Horizonte; and Anita Schwartz, Rio de Janeiro), that casts a shadow over the main exhibition hall below.

The dangling footpath that sways and rocks to the buzzing crowd all around stands as an informal line of demarcation, dividing the pristine upper floor, where works stand free of constraints, and the packed fury of sales at booths and stands throughout the rest of the pavilion. In all its uselessness, it’s a symbol of fairs’ deepening crises of identity as they increasingly want to resemble institutional exhibitions. When it comes to this particular building in Ibirapuera Park, the crisis is even more resonant. Home to both the fair and the Bienal de São Paulo, the most traditional art show in Brazil and second-oldest biennial in the world, the space itself seems to lend legitimacy and museum status to just about any work it comes to house and ends up turning a commercial event into some kind of spectacular affair.

Segregated from the rest of the show, the installations and sculptures upstairs do pack more punch. One sequence in “Open Plan” curator Jacopo Crivelli Visconti’s selection is especially powerful. Ricardo Basbaum’s Conjs (2011), a set of benches and metallic structures, presented by Luciana Brito, São Paulo, functions as a waiting lounge where visitors can sit and listen to a recording with a deep voice hypnotically repeating “sit, cross, jump” on headphones. This desire for movement, echoed by Costi’s bridge, sets forth a string of works that have motion as a central element or conceptual anchor, going from the paper spheres that float above air currents in Attila Csörgö’s How to Construct an Orange II (1993–2006, presented by Gregor Podnar, Berlin) to the dazzling effect of blue sheets of acrylic that make up Julio Le Parc’s Sphère Bleue (2001/13, presented by Nara Roesler, São Paulo), one of the most striking pieces of the fair, though nothing new in a market that craves kinetic masters of all sorts.

Next to the ethereal blue sculpture, a series of untitled heavy steel works (1995) by Brazilian concretist Amilcar de Castro, and presented here by Marilia Razuk Gallery, São Paulo, makes a counterpoint. Champion of the cut-and-fold method, de Castro found a place for himself in history by making brute metal seem pliable and soft, responding to one simple action: a cut and a twist. In dark hues, they lie low, hugging the ground, almost an ode to weight and stability that make Le Parc’s work appear rather frivolous, an exercise in nothingness or a desire to float indifferently above everything else. Neïl Beloufa’s Happiness Bleecher, Communities, Growing Up and Corruption (2014, presented by Mendes Wood DM, São Paulo) adds a layer of reality and dirt to this more formalist set of pieces. His installation is a castle of sorts made from urban debris, from plastic bottles to cigarette butts, and topped with plastic grocery bags congealed in flight, as though flags ornamenting ugly towers.

In this section movement—or its awkward interruption—is key. Fernando Ortega’s delicate sculptures with sheets of glass balanced on the tip of a bullet or the edge of a rock (presented by Kurimanzutto, Mexico City), and Mona Hatoum’s Turbulence (Barcelona) (2012, at White Cube, London), a square of marbles on the concrete floor, are both stunning for the same reason: arresting motion in precarious equilibrium. It’s a message that also seems to underlie the narrative in Daniel Buren’s massive and colourful installation A Cabana Explodida, Obra in Situ, Homenagem a Oscar Niemeyer (2015) at Galleria Continua, San Gimignano, where glass walls envelop the viewer, mimicking the shapes of Niemeyer’s windows out onto the park, while adding layers and layers of reflections and stripes in what the artist calls an “exploded hut.”

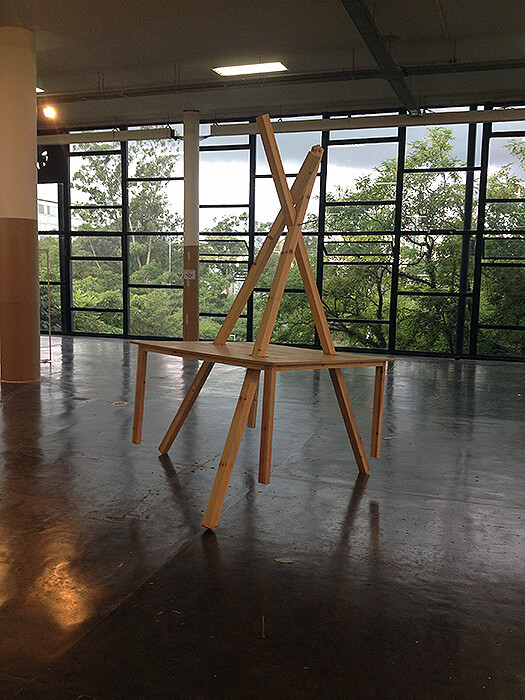

André Komatsu’s sculptures, presented by Vermelho, São Paulo, equally address this latent feeling of tension and despair. The artist, one of the three names chosen to represent Brazil at this year’s upcoming Biennale in Venice, builds what look like architects’ drafting desks in the series “Choque de Ordem” (2013), but they’re broken and jagged, pierced by tools or other tables, a comment on the fragile nature of planning and building in a country still regarded by its citizens as a nation of the future, always in progress and relentlessly corrupt. Komatsu, however, in a mute palette—all the wood in his pieces is raw and colourless—deconstructs the cliché of Brazil as a tropical, colorful place in order to shed light on the more disastrous aspects of its reality.

The sublimation of color and the retreat toward austerity seem to be at the heart of the best works at the fair. Fearing Brazil’s economic collapse amidst the latest corruption scandals, gallerists toned down their selections to pieces that are less festive and celebratory. Monochromatic paintings and sculptures, especially white ones, were omnipresent. New York’s Gagosian had a small Achrome (1958) by Piero Manzoni; the local Galeria Luisa Strina had several stark white pieces by Fernanda Gomes and Carreras Mugica had white papier-maché works by Juan Pérez Agirregoikoa; London’s Lisson Gallery had two photographs of white backdrops by Broomberg & Chanarin (NBC, CBS, UPN, ABC, FOX, HBO, and Toyota, Gap, Honda, Hummer, both 2009); and New York’s David Zwirner featured Jan Schoonhoven and Franz West all in white.

Two interesting works, also almost invisible, are Marina Weffort’s silk pieces (2014) at Marilia Razuk. They are delicately shredded and pinned on white canvas, creating a subdued optical effect or a slight radiance. Their next-to-nothing approach strangely recalls a performance held upstairs at the fair, where artist Anna Leite, wearing a white dress, slowly scooped threads of what looked like human hair covered in a viscous fluid and hung them on clotheslines running across the stage, leaving those black threads, dripping in ooze, suspended like strange fruits in the sun to rot (Diálogos silenciosos [Silence Dialogues], 2014). In a twisted way, all that hair, like the threads in Weffort’s pieces that could be likened to scalps displayed as trophies, reminded me of Ella Fitzgerald’s version of “Black Coffee” (1960), where she’s hanging out on Monday her Sunday dreams to dry.