Milk production in two very different countries is the departure point of British-Japanese artist Simon Fujiwara’s solo show. North Korea does not produce any fresh milk, while Israel’s milk yield per cow is one of the highest in the world. In concordance with these facts, Fujiwara collaborated with two kinds of producers: North Korean painters employed by the Mansudae Art Studio, a state-run facility which manufactures propaganda imagery for the government, and cows from the Israeli kibbutz Ein Harod, a highly lucrative producer of milk.

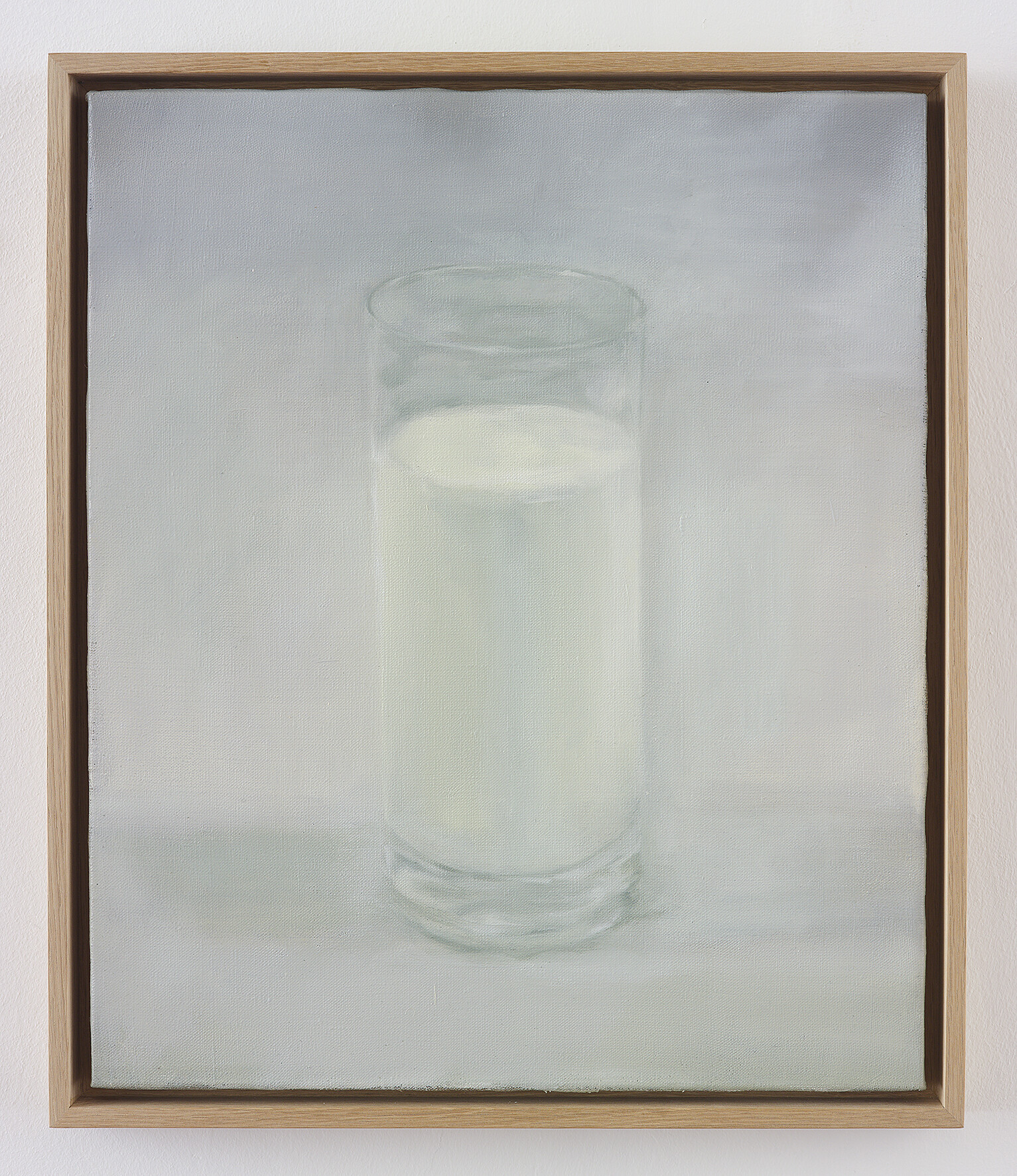

Shown on one floor, seven paintings commissioned from the North Korean artists all depict the same glass of milk (“Lactose/Intolerance,” all works 2015). Their techniques vary, displaying the artists’ style range, from nostalgic through hyperrealist to early Pop. The techniques are impressive, but, as we can anticipate of paintings created as commodities on demand, they seem poster-like, lacking any real affect.

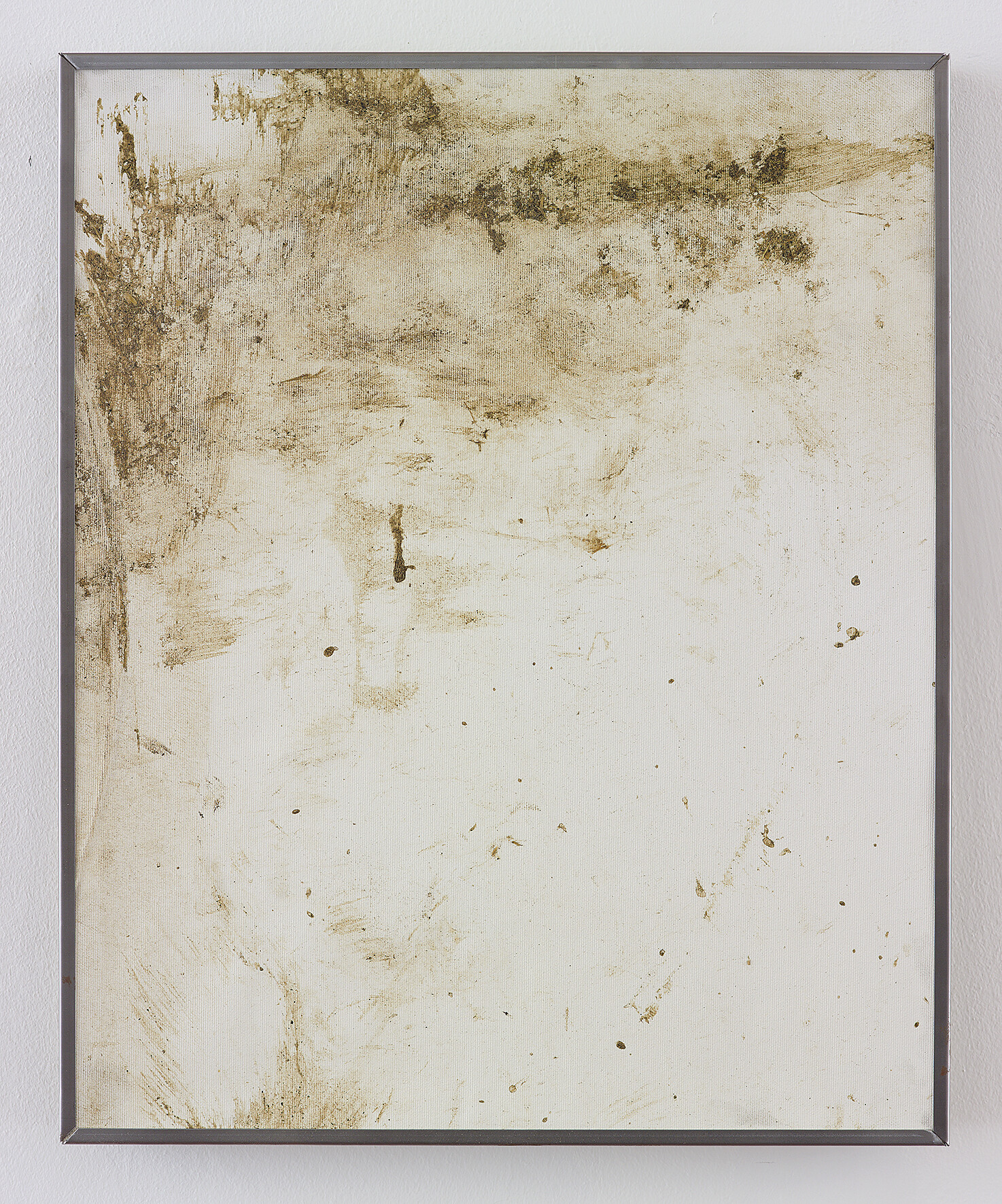

On another floor are a series of paintings made by cows, created by their excrement, which colored canvases positioned behind them during lactation (“No Milk Today”). The works are hung lower than the standard hanging height of an artwork, placed at the average cow’s eye level, and are unified in shape, size, and khaki shades. In this sense, they are reminiscent of the serialized production method of “Lactose/Intolerance,” thus implying that both the production of milk—as depicted through the cows’ labor—and its representation—as depicted by the Korean painters—are socially and economically constructed gestures. However, while the North Korean painters are automatically depicting a sterile final result, the cows’ byproduct is used to create unique “Abstract-Expressionist” paintings, with a personal signature.

One could mention similar artistic uses of feces, such as Dieter Roth’s multiples of straw and rabbit droppings, Bunny‑dropping‑bunny (1968, produced 1972–82); Chris Ofili’s frequent use of elephant dung; and, of course, Piero Manzoni’s Merda d’artista (1961). But Fujiwara’s adoption of manure is not cynical or provocative, nor was the manure chosen for its earthy qualities. Rather, it was appropriated for its specific use value. Ein Harod, one of the last kibbutzim to function in the Israeli early socialist spirit, based on equality and shared income, is known for its successful art museum. The cows’ manure, an organic material reused as fertilizer for crops on which the cows graze, is as inseparable from this social-economic-agricultural mechanism as the milk they produce—a Zionist national pride. Fujiwara’s works intelligently decompose representations of products, including art, in two problematic regimes that evolved from socialist backdrops, and whose own representation in the media is currently in the eye of the storm, greatly affecting their global positions.

As opposed to these two extreme cases, the last part of the show, located on the top floor of the gallery, includes two sets of works centered on a very different political identity, that of Germany. A ready-made sculpture series titled “Ich” (I in German) is composed of selected models of domestic trashcans produced in Germany, specially designed for waste separation in a country where recycling has become the norm. The bins, coated in liquefied bronze and positioned on pedestals, seem like weird combinations of minimalist sculptures and classic, figurative masterpieces.

Surrounding these sculptures are abstract paintings in pink and fair skin tones, made by the artist himself. These are fragments of a blown-up portrait of Germany’s Chancellor Angela Merkel, or, in fact, her makeup (“Masks (Merkel)”). After consulting Merkel’s personal makeup assistant, Fujiwara used the Chancellor’s specific makeup products and application techniques to create a representation of a personal, yet highly public, mask. Putting on makeup can be described as a woman’s social duty to erase her face and paint it anew every morning, much like the ceremony of disposing domestic waste. Both are everyday private rituals that, in a way, construct the self. Domestic waste is the leftovers of what one has consumed, and its disposal may reveal a great deal about an individual, while applying makeup constructs a public persona. However, the clever connection between the two series exists primarily in the public sphere: Merkel, in her famous 2010 declaration that German multiculturalism has failed1, has de facto demanded that immigrants be recycled into a German identity, an Ich.

This show varies from most of Fujiwara’s former practice, as he neglects his characteristic pseudo-documentary preoccupation with his personal biography. He does not play his typical roles of novelist, anthropologist, or archaeologist, but takes on the position of the curator, with which he has experimented in various previous shows: in his early project The Museum of Incest (first exhibited at the Royal College of Art, London, 2009), he designed an alternative natural history museum; in his major show at Tate St Ives, “Since 1982” (2012), he integrated works from the museum collection into his installation; and recently in “History Is Now: 7 Artists Take On Britain” (2015) at the Hayward Gallery, he exhibited a meticulous selection of objects and artworks side by side, in an attempt to draw a portrait of current British mentality. In his current show, Fujiwara further develops this intriguing practice to explore the impact of global and local economic forces on art production, while synthesizing this immaterial narrative into the objects themselves.

“Merkel says German multicultural society has failed,” BBC News, October 17, 2010. Last accessed April 6, 2015.