“Tropenkoller” translates from German to English as “tropical frenzy,” but the climate seen in these ten pieces collected over the last five years and exhibited at Modern Art, London doesn’t really come from anywhere other than some intoxicated area within Lothar Hempel’s brain.

Throughout the two decades of his career, Hempel has tasked himself with the outlandishly difficult job of finding endless new ways to be strange—almost to the point of impenetrability. This activity has produced many enigmatic tableaux, staged with defaced cut-out figures and sculptural props—Slowdance (2015) includes a gnarly tree limb emerging from a stretch of painted steel—alongside gleefully mysterious collages. “Tropenkoller” tracks the sly continuation of Hempel’s venture at all its varying levels of opacity while capturing a fresh surge of invention that makes it feel more attractive and baffling than ever.

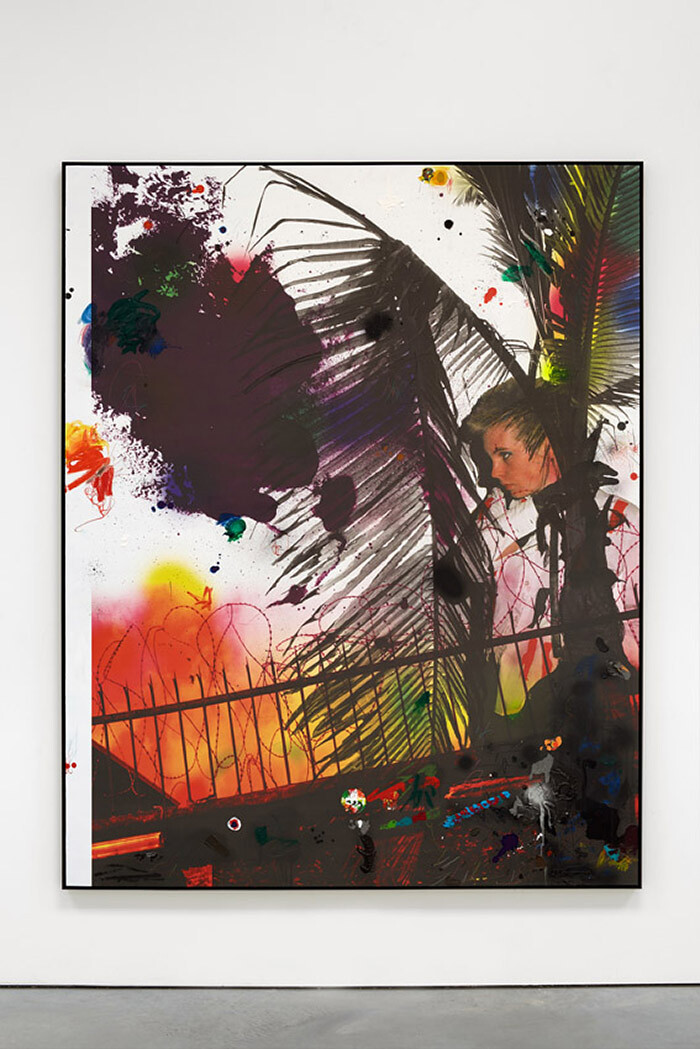

Arranged in their funky rhomboid frames, collages predominate, but there are two cut-outs stylishly adrift in the gallery’s main room. All the pieces encourage off-beam critique and outré guesswork while looking like a bunch of vaguely menacing hallucinations. The skies in Hempel’s collages come freaked with colored wire to short-circuit their holiday slideshow familiarity, or abstracted by inkjet pixelation into pure cosmic glitter. In the photomontage Storm (2015), the sun is a big black absence carved out of a borrowed photograph. Enjoying this bizarre meteorology is also a way of following the manic textural variegation of the show’s contents.

Nature Morte (2015) counts among its materials a grungy cut-out depicting a Japanese girl from a horror flick chewing pensively on a squid tentacle and a tangle of dry roots that suggests a clutch of withered snakes. The tentacle and the root neatly resemble each other, like two things drawn moments apart from the same maze of free association.

Storm features a foam target with a rush of wires at its center, which is affixed to the head of a monochrome Indian queen. Thanks to a manipulation of scale, she’s a giantess juxtaposed with a snapshot that shows American suburbia retouched as a psychedelic jungle: clumps of glowing foliage on all the lawns, the road to the mountain transformed into a river of gently modulating colors, shifting discreetly from metallic green to cough-syrup purple. Hempel’s ambition is seemingly to rebuff wave after wave of elucidatory strategy until what remains is the pure surf of bedazzled thinking, playful questions, and eccentric possibilities. The conjunctions of clouds, houses, and the woman hint at some unsettled psychic weather but they also reverberate with threats of radiation amidst more chaotic intimations about brain activity, science fiction, and dream theory. Though Hempel is an expert at building such conundrums he doesn’t always succeed in making them beguiling, but his sloppier works indicate how narrow the gaps are between intrigue, bemusement, or sheer indifference and they might provide the only route into comprehending the cognitive oddity of what he’s attempting.

Jetsam (2010) unrolls a reproduced photograph of a traditional American daydream—the nuclear family in the convertible—onto a stainless steel representation of a sailboat. There’s Dad at the wheel, exultant in shades, as Ma and the kids shadow him anxiously in the back. A striking image anyway, but wait for the punch line: we’re in the middle of the ocean. The family drive is presumably being chronicled for a frisky early 1960s photo-essay on the short and doomed life of the amphibious car. Alongside the strange symbolic undertow of the whole scene, which could depict derangement or a family in dissolution with equal smoothness, there’s also the witty minimalist installation above the boat that approximates sea and sky via two fabric squares in differently shaded blues. The resultant assemblage is at once obvious, goofy, and calmly perverse. If Jetsam feels more like a wisecrack than everything else, it aligns with the other works that raid the past to conjure up futuristic meetings of surfaces and activities still too peculiar for our environment to accommodate. But it’s a wickedly illustrative joke, too, because logical certainties are so often hard to find in Hempel’s work: whatever you thought was dry land frequently turns out to be water.