Behold: a red headband-wearing cat warrior brandishing a gold-plated .45 automatic astride a rearing white unicorn that breathes fire; all this in front of a rainbow, some violent explosions, and a castle from Super Mario. No, this isn’t my fantasy, it’s simply a Google image search return for “what does the internet look like.” If I were on some strong psychotropic drugs, an auditory hallucination might have ensued stating how the depiction was “like the new Napoleon Crossing the Alps.” Although I am stone sober, that doesn’t mean that I will not now trip out.

Just as my above association might make the eighteenth-century painter and propagandist Jacques-Louis David turn in his grave, I tend to cringe when I hear the term “post-internet art.” Particularly because most of the work sold under such a label has more to do with tried and true techniques of collage, appropriation, and de rigueur concerns of cultural capital than the ever-growing macro politics of planetary-scale computation. In actuality, post-internet art’s instant popularity probably stems from the trend’s familiarity to older styles, a sort of Pictures Generation 2.0 seamlessly dragged to market to perpetuate the kind of subjectivity-building exercises that the philosopher Gilles Châtelet dubbed as “consensus fodder.”1 And while I might hold a soft spot for the new forms and shapes which the transgendered and queerer side of the discussions surrounding art’s relation to the internet present, I wonder about the other strange orifices now ripped into our very spines from which ubiquitous images of war, exploitation, and other pornographies pour out and are traded. To recuperate the lost art of disruption—a notion the tech industry stole from modernism so as to defang it—could now be the time to play the web against itself? And if so, to what end? Toward such concerns, I was delighted to eye John Gerrard’s Farm (Pryor Creed, Oklahoma) (2015).

Following a denial of access to a Google server farm in Oklahoma, the artist hired a helicopter to survey the industrial complex from the air. There, giant diesel generators and cooling plants flank the depopulated factory through which our daily wants and means are now trafficked and sold. Gerrard’s recon furnished enough photographic material for the artist to CGI model the façade in todo. In turn, this rendering was sent through a game engine to furnish a hypnotic 360-degree animation, which ceaselessly sweeps around the model at a set inclination. At Thomas Dane Gallery this synthetic POV-shot was projected so as to ape the traditional film loop even though it’s the product of a software framework that renders each and every frame mathematically. Imitation suns rise, set, and cast shadows over the complex attendant to the real-time solar calendar for the actual site. Yet no visual data is stored in the work; each frame replaces the next and is disposed of so that algorithmic procedure takes precedence over all content as the simulation indefatigably rolls on hermetically. And while a trained eye might read various aspects of the façade, the scene is no more transparent than a quotidian Google street view—even if Google wishes to hide it. So then, what is really on view in the gallery? In the most basic scene, the work not only speaks about computing, it is computing itself; however, a fuller image of the internet can be gleaned by viewing the second of the two works on show.

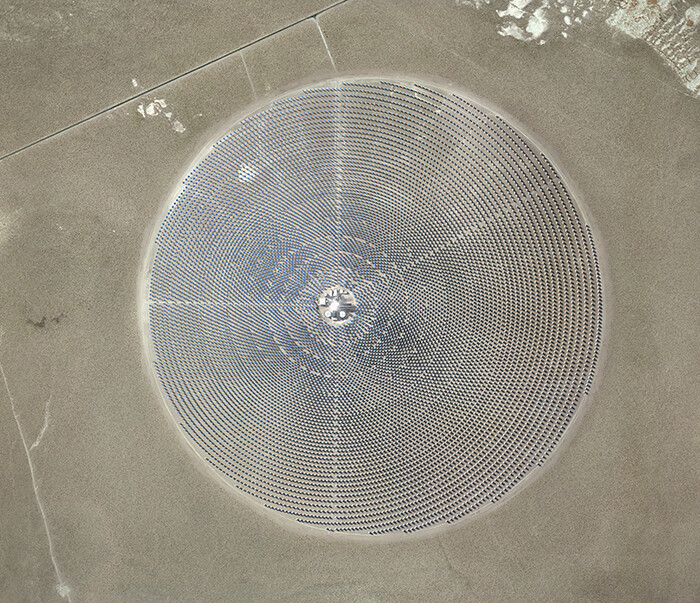

Gerrard also presents Solar Reserve (Tonopah, Nevada) (2014), a projection that animates a CGI model of a billion-dollar solar power plant in Nevada, which utilizes a proprietary digitally controlled mirror system to superheat salt to such extreme temperatures that the plant can produce energy even at night. While it almost goes without saying that these twined works suggest the resource hungry nature of our devices, another pertinent question emerges: how are we positioned within this digital-industrial complex?

Although the so-called post-internet art might speak of network dissemination, what this kind of work callously takes for granted—and even extolls—is that there is a network at all, or worse, that all networks are equal. While the renewables implied in Solar Reserve (Tonopah, Nevada) can be seen as step toward a cleanly powered networked system, both of these enterprises embody the cost-prohibitive techno-capital system that designs hidden structural advantages into its privatized infrastructure so as to sustain an endemically asymmetrical form of economic dominance from which few can escape. Although the internet is a place for exhibitionism, what it inhibits and regulates needs to be understood as well. While this short review is no place to go into these intricacies, let’s take Google’s PageRank, that bastard son of cultural capital commoditized, as a quick and dirty example of how quantification bifurcates reality into two camps with differing privileges.

In this famous algorithm, which orders and ranks internet searches, and thus secretly “curates” access to information, import is not measured by the content of a webpage alone, but is measured by its links instead. Through this rubric an article or artwork fractures into two simultaneous existences: the thing itself, and its trade as an object to market Google’s advertising services. Items begin to hollow as they are subordinated toward other ends. Within this context, what kind of agency do ideas have when a new class of owners reassigns them as financial instruments regardless of substance and abstracts them from their producers? Likewise, what good do these truly zombified abstractions provide as Google gets more powerful every day from hosting them, and as the general economy splits into greater wealth disparity? In order to hack into this and other divisive web dynamics, a new kind of discursive internet literalism is necessary.

Luckily, artists such as Trevor Paglen have already begun the hard work to delineate the clandestine nature of how the digital-military-industrial complex is controlled by depicting the various black sites, buried cables, and the strategic placement of satellites put in place so as to create a fresh panopticon built not on visual control, but on the centralized and veiled control of information. Not surprisingly Gerrard, like Paglen and Harun Farocki before him, has looked into the same hazy digital netherworld in his previous work. Returning to the economy of shattered and split imagery though, what the work here hints at through its hidden-in-plain-sight pseudo-transparency is that digital barons function like bookies; no matter what images we trade, they still get their commission. While it is always desirable to read images iconographically, when it comes to the internet, to only do as such would be to practice a kind of post-internet “art lite.” What is deeply needed is to watch how the web is physically spun so as to see how those strings are pulled. To borrow a popular phrase: don’t hate the player, hate the game, but more importantly, learn how that game is currently rigged.

Gilles Châtelet, To Live and Think Like Pigs: The Incitement of Envy and Boredom in Market Democracies, (NY: Urbanomic/Sequence Press, 2014).