Daniel Malone is not a painter, but his current show is full of paintings. And while it may be a solo exhibition, there are two artists in the room. The second is Colin McCahon—but more about him in a minute. Upon entering Hopkinson Mossman’s gorgeous, bright white gallery space, the paintings were something of a head scratcher. They looked distinctly not contemporary—neither in palette, nor in composition, nor in iconography. I made an overconfident and undereducated snap aesthetic judgment: Sigmar Polke by way of Robert Motherwell. But I stayed with the paintings, and they began to disclose themselves over time, as paintings tend to do. Or, to paraphrase another twentieth-century painter, Philip Guston, the “information” may be fast, but the painting is slow. My information, it turned out, was wrong, but its wrongness may be instructive.

Daniel Malone is a New Zealand artist who moved to Poland seven years ago, but has spent the past couple months in residence at Parehuia, the McCahon House Artists’ Residency outside of Auckland in Titirangi. In the 1950s Colin McCahon (1919–1987) lived here with his wife, artist Anne Hamblett, and their four children, on French Bay among the native Kauri trees, which can grow to 50 meters tall. McCahon is New Zealand’s best known artist—a modernist painter during modernism, albeit something of an outsider. McCahon’s art “gave New Zealand a powerful visual identity”1—no small feat.

What I failed to recognize, then, was the iconography of a nation’s most known and mythologized artist. That, for example, the black and white checked pattern of the draped canvas in Cloak for a Cleaner/Curator (2014) would have been instantly recognizable as citing the iconic black and white checked jumper McCahon often wore in photographs. Further down the symbolic rabbit hole is the painting’s shape, a swath of fabric loosely draped around a wooden T, a nod to McCahon’s job as janitor of the Auckland Art Gallery before being promoted to curator (there are pockets of myth at every turn, as is always the case for history’s great artists).

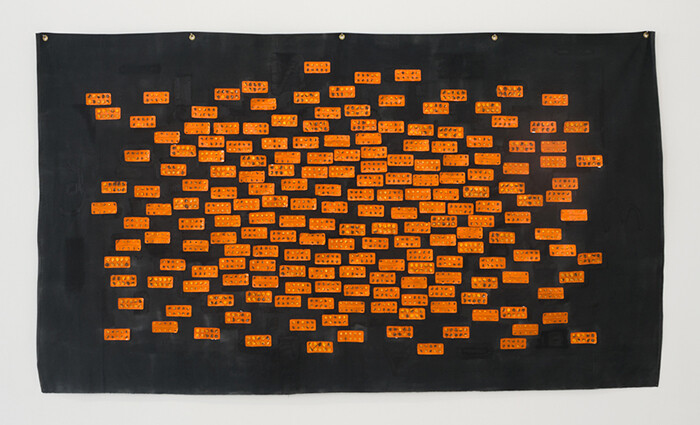

Cloak III (The Wretched of the Earth) (2014), a coolly evasive and information-packed conceptual self-portrait, stands opposite the checkerboard. Apparently Malone is a pack rat—ahem, collector—and sewn across the raw, unstretched canvas are the laundry care tags and brand labels from clothing he’s presumably bought from H&M and Calvin Klein and Benetton and D&G and Zara. The three works in this first gallery, all titled Cloak, are garments as much as paintings. In the next, larger gallery, where paintings hang more properly on walls, Arhythmia (2014) echoes the price tag self-portrait in a wretchedly formal way. A heavy drop cloth painted with black Solpah, an enamel housepaint McCahon also used, is speckled with metallic orange emptied pill packets, the residue of Malone’s daily treatment for a heart condition. Maybe this painting looks like a McCahon, but if so, I couldn’t find the one it is meant to reference. I thought again of Guston, whose fields of shimmering, short brushstrokes become wounds or windows.

So there is plenty of Daniel Malone here, and plenty of Colin McCahon, though it takes some effort to disentangle the two. Artists have taken on other artists’ work, appropriating or attempting to remake it, but this is something altogether different. It matters that Malone spent his days where McCahon lived out in the Titirangi bush, the non-painter holding a brush and staring down a canvas. What kind of artistic act is this? What kind of process? It feels more like a channeling or conjuring than an appropriation, more like a kind of possession (I wonder if Malone knows the exquisite 1981 film Possession, made by Polish director Andrzej Żuławski, who pitched the film to his American producer as “a film about a woman who fucks an octopus.”)2

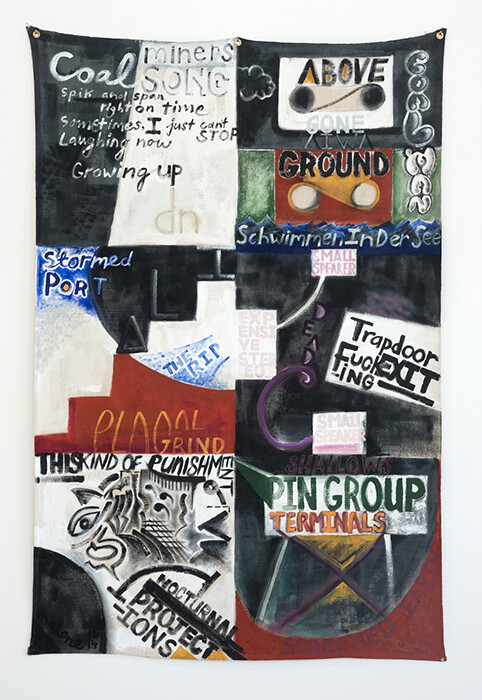

As Derrida proposed in Spectres of Marx (1994), we must “learn to live with ghosts” by learning “how to let them speak or how to give them back speech.”3 McCahon’s speech has been mediated by many people for many ends. Malone points out that, for example, McCahon’s visual idiom was used by South Island post-punk bands in the 1980s that “rate” much higher among certain demographics than McCahon himself would. He stitches the album covers into one painting, Six Dais in Otago & Canterbury (2014). The layers are endless—I haven’t even touched on orange juice or Rastafarianism. The latter provides the exhibition’s title, “I&I,” and is surely a counterproposition to McCahon’s own assertion, painted directly onto canvases, “I AM,” which feels so hopelessly inaccessible. That an artist who doesn’t paint would engage with the most celebrated painter of his own country via painting is a risky move. It helps that McCahon’s own reception has been so diffused and varied and unexpected, and it helps that Malone took his task seriously, and made paintings that are sincere and convincing.

Rudi Fuchs, “Colin McCahon: A Note” in Colin McCahon: A Question of Faith, eds. Marja Bloem and Martin Browne (Amsterdam: Stedelijk Museum Publishing, and Nelson, New Zealand: Craig Potton Publishing, 2002), 12, quoted in “External Links and Sources,” McCahon House, last accessed February 20, 2015. http://www.mccahonhouse.org.nz/TheHouse/ExternalLinksAndSources.aspx.

Julian Myers, “Introduction to Possession,” Cosmopolitan Review, last modified April 22, 2012. http://cosmopolitanreview.com/pmn-julian-myers/.

Jacques Derrida, Specters of Marx: The State of the Debt, The Work of Mourning & the New International (New York: Routledge, 1994), 132.