Jochen Lempert’s work is often presented in large compositions of black-and-white photographs demanding close inspection. This time is no different. Ranging from medium-sized to small and tiny prints, this exhibition of his now classic repertoire of flora and fauna gives visitors the feeling of being at an amateur’s show, where the standards of high-end presentation have been disregarded. Since the early 1990s Lempert has been known as the photographer who was once a biologist, and with this knowledge the scale of the gallery space seems ideal; a room not big enough to belittle such subtle work, which could easily be confused with scientific materials of a lesser order. Although most of the photographs in the show are organized in diptychs, triptychs, and series including several pictures, the visitor is easily drawn into the detail. A few steps away from the wall it all looks like a harmonious world: natural objects from different orders merge into seamless forms.

But upon closer examination paradoxical connections manage to unsettle what at first glance seemed unproblematic. A shelf with eight photographs and one photogram (Botanical Box [2014]) emblematizes this type of composition. Among the diverse typologies of leaves depicted there sits a blurry reproduction of a Hans Arp wooden relief. The organic rhythms of the avant-garde vocabulary resonate on a formal level with the rest of the images, both fusing discreetly into the wider ensemble and striking a chord of dissonance.

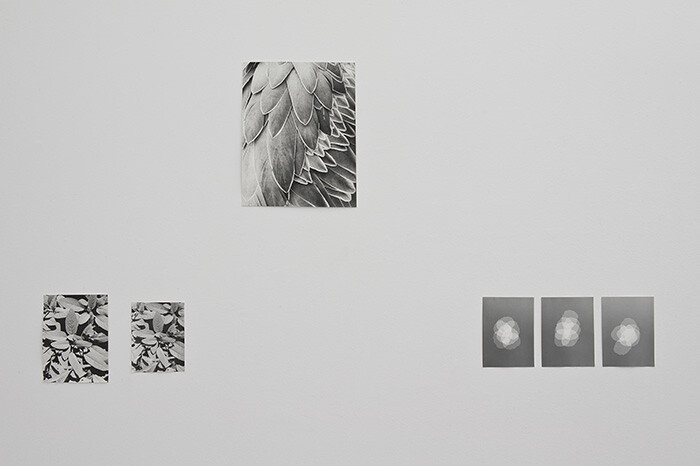

Here, it is the photographer’s behavior in front of a myriad of objects—including those from both natural and urban environments—which is the subject of this exhibition. The transformative, scientific qualities of animals and flowers are celebrated ironically—it’s Darwinism at its best. While Salvia (2014) and Untitled (Feathers) (2014) suggest a certain degree of kinship, in fact they have nothing to do with each other, so the result is totally speculative, like an evolutionary theory gone astray. Lempert’s photographic series depart from similarities based on form; his morphological inventions open up different possibilities. Either he is acting as a street photographer whose silver gelatin prints have been unsuccessfully colonized by the themes of the former biologist, or else he is decidedly dissolving categories like “natural” and “artificial” that have been long set apart. Many of the vegetal motifs in the show are just printed patterns on clothes claiming a life of their own. In others, the natural element appears amidst the urban. As such, Lempert’s photographs may well depict an ecology far more complex and politically ambitious than the one that preserves human superiority over nature. By humanizing what is not supposed to be human, he has acknowledged a subjectivity usually denied to the other species that share this earth. Here, the composition of his exhibitions—similar to his earlier displays—allows objects to enter into an unexpected dialogue. One might conclude Lempert is a defendant of the rights of nature, someone for whom the ecological perspective is not lyrical, but political.

To convey such an ambitious, political program with his humble photographs taped on the wall reinforces the utopian aspects of this project. With the edges curling away, Lempert’s photographs look precarious. The means of production and the aspirations are so disproportionate that one cannot help it but feel sympathy for the photographer’s position. He is an artist who faithfully believes that nature will speak by itself, this being the ultimate goal of this project. Thus the photographer is no longer a witness, but a vanishing point about to disappear. A photograph depicting an eye tattooed on the back of a woman, Untitled (Eye) (2013), seems to play with the idea of a world which is no longer out there to be looked at. Images of flowers and birds emerge as heroic characters with personalities that challenge the visual field dominated by the human gaze. From now on they are the ones looking at us, Lempert seems to suggest.

I felt this clearly when I was staring at the smallest photograph in the show. Untitled (Landscape) (2014) measures 3.2 by 5.4 cm and all I could see in the gallery light was the stark contrast of land and sky. Who could dare to imagine anything else on such a tiny scrap of paper? No wonder I failed to spot a hare standing up in a field, my eyes unable to look so microscopically at the image. Another photograph nearby of a street, taken from high above, took me a while to unravel. In the middle, amidst cars parked on the street there was a beautiful butterfly, sharp and focused. As the title, Vanessa atalante migration (2014), discloses, she is flying her way through the city. Life is lurking in the least expected places. And as Lempert’s work makes clear, it takes a political, earnest approach to his images in order to see it.