Entering Galleria Guida Costa’s diffusely lit gallery from their front reception room to see “Men’s Talk” feels like entering some kind of illicit and profane chapel. Whilst the space—which occupies an old print workshop a stone’s throw from Turin’s main railway station—bears distinct traces of its past, felt through its concrete floor and yellowing walls, its current exhibition invites contemplation on works of iconographic scale.

The exhibition of Boris Mikhailov (b.1938) is the first in a series on the work of the Ukrainian photographer who came to prominence when he moved to East Germany from the Ukraine shortly after the collapse of Soviet Union. His social realist images portraying drunkenness and destitution both before and after the end of Soviet rule helped make him one of the most important Soviet photographers of his generation. “Men’s Talk” exemplifies the artist’s inquiry into what the he calls “the pure force of human being,” following the lives of a gay couple who were asked by Mikhailov to interact within the “set” of a prison cell in Ukraine over an evening. It’s left radically unclear, though, as to whether the couple are really incarcerated there, or merely inhabiting the space for the images themselves.

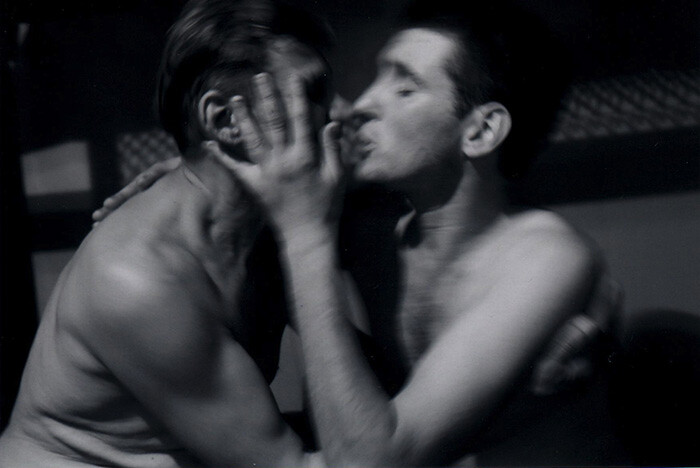

The resulting analog photos display a disjointed narrative, ranging from a portrayal of tenderness and fragility to one of aggression and, at points, sarcasm. A scene of a dinner cooked with the barest means—a frying pan nearly spilling over with meat and potatoes—stands as a kind of cipher for the lowest common denominator of food shared between men. A nearby scene shows the couple on a sofa adjacent to a table; one is sprawled on the other yet facing the camera, arms aloft in a crucifixion pose. Next to the sofa the frying pan rests—its contents barely touched—on a makeshift coffee table littered with empty glasses. The scenes feel like a kitchen sink drama crossed with Punch and Judy’s show of playful, but disturbing, violence. This is accentuated across the images by the alternation between tender embraces and the play-acting of sexual acts such as spanking and implied anal sex. Their interaction, which almost shows contempt for the camera and public, appears to mock the absurd situation which the two protagonists find themselves in, “acting” themselves.

The series raises important questions about the documentary photographer’s method. After all, to what extent is it possible to separate reality from fiction where the camera intervenes and people assume a role as the photographic subject? What “Men’s Talk” shows, with great affection, is the vulnerability of the subject under the gaze of the other, as the pair lay bare their most tender and intimate moments—however crude or staged—for the camera.

Far from the self-conscious and individualist era of the smartphone selfie, Mikhailov’s images evoke a bygone era where photography demanded a sense of performance: the act of posing had a value in the present moment, rather than being a means of producing an image for uploading to social media. In continuing to use analog, Mikhailov keeps alive the “act” of photography as a physical one which reveals much about the human condition—and as one concerned with acts lived for the moment in physical space. True, smartphone photography may figure a need for expression too, yet it’s somehow more eerily removed from the realm of physical interaction.

On November 8, 2014 as part of the “Notte dell’arte” initiative—in which tens of Turin-based galleries timed their openings with the end of the Artissima Art Fair—Galleria Guido Costa added a triptych of color self-portraits to “Men’s Talk.” The same repeated image is displayed three times in a row: once in true color; once adjusted to accentuate the blue; and once to accentuate the green, providing an uneasy and sickly trio. The image features the artist naked and crouched beside a patio door left ajar, which leads out onto a domestic garden. Side on and knees bent, Mikhailov appears as an ordinary man; weak, and unattractive. If this photo is staged—as it surely is—it demonstrates the possibility for portraits to portray a moment of honesty amidst the deception. After all, all art is staged, yet Mikhailov’s images allow the staging to reveal some real and vital facet of humanity.