Since Susan Sontag announced the demise of cinephilia in her prescient 1996 essay “The Decay of Cinema,” discourses around the death of cinema have been widespread, fuelled in part by the replacement of celluloid by digital technology. Since our understanding of the world has been so influenced by movies—one irrevocably conditioning the other—cinema’s apparent passing has caused pain, and trauma.

By 2012 the digital takeover of film exhibition was complete. It had been threatened for almost a decade, but it was nevertheless shocking to see 35mm projectors evicted from projection booths across Western Europe and North America. Only a year earlier, British artist Tacita Dean had declared that UNESCO should recognize film as part of a universal cultural heritage, paying homage to it with her installation FILM (2011) at Tate Modern, London. The Austrian filmmaker Peter Kubelka labeled 2012 as film history’s darkest year, and produced Monument Film—a work which is impossible to stage digitally—“as a call for patient defiance.”1

Whether working with film, painting, or photography, Los Angeles-based artist Morgan Fisher produces works that closely examine their medium. Best known for his 16mm films, which bring together industrial film practices and visual arts strategies, Fisher is a conceptual filmmaker who turns film into a form of research. In the aftermath of the digital takeover of cinema, “Past Present, Present Past,” Fisher’s first solo exhibition at Maureen Paley in London, provides a timely and poignant reflection on technological obsolescence and the death of analog film.

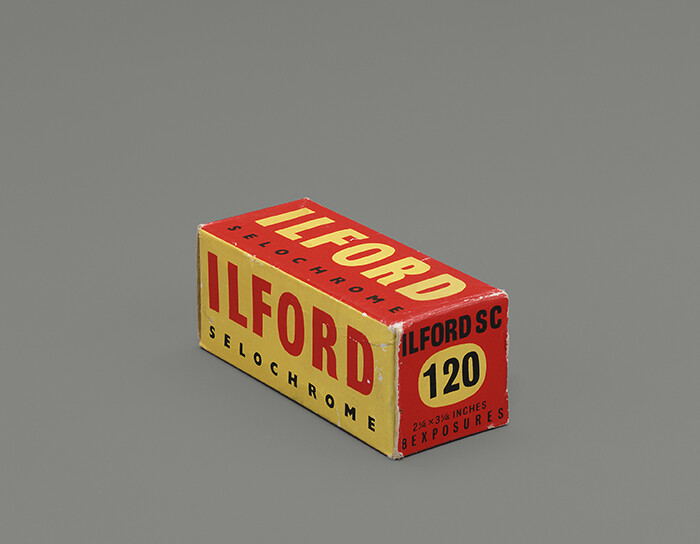

This is most explicit in a series of 12 new photographs of unused boxes of still film from the 1950s, the decade when the artist’s father introduced him to photography. Not only do most of these manufacturers no longer exist, but the expiration dates printed on the boxes are now long past. As Fisher writes in the exhibition notes, they are useless, “at least with respect to their original purpose, their uselessness underlined by the fact that photography on film as an amateur practice is essentially extinct.”

The photographs are displayed together with two older works: one of Fisher’s early films, Production Footage (1971), and a video diptych, Red Boxing Gloves / Orange Kitchen Gloves, that was originally shot on Polavision in 1980. The double screen video projection of Red Boxing Gloves occupies the exhibition space downstairs. Upstairs, the twelve photographs—arranged symmetrically in rows of six—provide an anteroom for the custom-built cinema where Production Footage is screened on 16mm.

In Production Footage, Fisher stages and documents an encounter between two models of 16mm cameras—a Mitchell and an Eclair—and the two modes of filmmaking that they represent: Hollywood and independent cinema. The film, modular in its composition, as are most of Fisher’s films, consists of two shots of equal length. The first shows fellow filmmaker Thom Andersen loading a 200-foot roll of film into the Mitchell camera. The second, shot by Andersen on the film that we’ve just seen loaded, shows Fisher unloading a 200-foot roll from the Eclair. In many ways, this is a quintessential Fisher film. Similarly to Production Stills—shot the previous year, in 1970, but not included in this exhibition—it is a film that documents its own production. But here the artist does not resort to the mediation of photography. Rather, he documents the making of the film directly on the film itself. Production Footage operates in a mode of contrast and contradiction, between movement and stasis, color and black-and-white, and ultimately between two distinct and conflicting forms of cinema.

Both the Mitchell and the Eclair were standard machines until not long ago, but here they appear as vintage objects from a distant past. So too does Polavision, the instant movie camera system developed by Polaroid, which became obsolete upon the arrival of the videocassette. In fact, it had already been discontinued by the time Fisher shot Red Boxing Gloves / Orange Kitchen Gloves.

At first glance, Red Boxing Gloves / Orange Kitchen Gloves does not appear as traditional Fisher territory. Two pairs of hands caress two pairs of gloves, which in their odd sensuality become suggestive of male and female positions. The subject is complementarity, and the pairings that it implies: between color opposites (red gloves against green background; orange gloves against blue), between left and right projections (and left and right hands), and ultimately male and female attributes, the subject of the pendant pair being one that Fisher has continued to develop and explore in his painting.

Fisher’s films were made as reflections on their medium: film as a material form, as a set of technical procedures, or as an institution. He is neither a romantic nor a fetishist, but nostalgia is prominent in this exhibition. He says in the exhibition’s press release, “I believed that photography and film as I found them in the 1950s would last forever.” At a time when we can no longer be certain of what cinema is, Fisher’s work reminds us of what it once was.

Peter Kubelka, quoted in Stefan Grissemann, “Frame By Frame: Peter Kubelka,” Film Comment, Sep/Oct 2012, Vol. 48 Issue 5, 75. Accessed online January 22, 2015, http://filmcomment.com/article/peter-kubelka-frame-by-frame-antiphon-adebar-arnulf-rainer