“On a Critique of Spatial Reason” could be the subtitle of Runo Lagomarsino’s current exhibition “Against My Ruins” at Nils Stærk. Upon entering an old factory hall, the gallery appears quiet, and in an almost overwhelming way, the works are conceptually ordered. But after leaving the space, the spatial order shifts towards a space of capitalist realism and its violent power until today. Throughout the twentieth century, entire generations have been articulating social rage by inventing anti-capitalist countercultures and movements in culture and politics. The pivotal moment is when one must finally clash with the dominant order such that only its shards remain to testify against the system’s presumed invincibility. But how can anger be articulated both as a passive stimulus-response scheme, and as an expression of active resistance against hegemony? What would aesthetic resistance as a form of anarchy within the space of artistic practice actually look like?

Lagomarsino’s video More delicate than the historians are the mapmaker’s colours (2012–13) offers us one key example. Like a one-finger-salute, the artist and his father throw raw eggs at Russian artist Zurab Tsereteli’s El nacimiento del Hombre nuevo [The Birth of the New Man], a monument that was originally built in commemoration of the 500th anniversary of the “great discovery” of the Americas. The statue of Christopher Columbus, standing 32-meters-tall inside of an eggshell, symbolizes the former colonial power of the Spanish empire. Even though it remains a Sisyphean task to damage the statue, the video, shot with a handheld camera, documents the father and sons’ act of anarchy with only the sound of the early morning birds to be heard on the soundtrack. One by one, they very carefully unfold the wrapping around the eggs (which were imported illegally from Buenos Aires); soon thereafter, yolk slowly slides down over the statue’s bronze surface. Defacing the surface as an act of empowerment? The two men are then seen from behind, exiting the Parque de San Jerónimo in Seville, which was built for the Universal Exposition of Seville (Expo ’92) and is where the monument continues to stand. What remains is not only the act of empowerment, but the physical act of throwing (stones, grenades). The intention of this work seems to be about appropriating history, repeating a pre-existing action. However, it is carried out from a different point in history, and thus, a different point of view. This artistic strategy is a thread that runs throughout Lagomarsino’s exhibition.

More commonly referred to as El Huevo de Colón [The Egg of Columbus], the statue makes reference to English artist William Hogarth’s well-known engraving Columbus Breaking the Egg (1752). Even though it has often been quoted and also criticized, the key moment in the saga is when Columbus upstages his skeptics by getting an egg to stand upright on the table simply by cutting off its tip. With this single gesture Columbus is said to have asserted his self-empowerment: “You could have easily done it, but I have done it.” This story exemplifies how one’s own pride might be revealed by the ridicule of others. And history repeats itself again: the men surrounding the table depicted in Hogarth’s engraving have divided the Americas according to their power. In 1885, another engraving made after German illustrator Adalbert von Rößler’s drawing Die Kongokonferenz in Berlin (1884) captures how the European powers, headed by the German Emperor Wilhelm I, divided Africa up amongst themselves with a map. In both of these images, the representation of continental spatial order as form of violent human power plays a key role: on the one hand, there is Columbus, a single individual, and on the other hand, there is a cartographic illustration.

Lagomarsino’s engagement with these themes could be described as a work of displacement. Nothing seems fixed any longer, and resists standardization. Even the artist’s remake of this theme is entitled Europe is impossible to defend (2013). The space of globalization—understood as a continental or cartographic space—becomes a fetish of identity building in his works, with the anachronisms of history questioning the normative concepts of space and time.

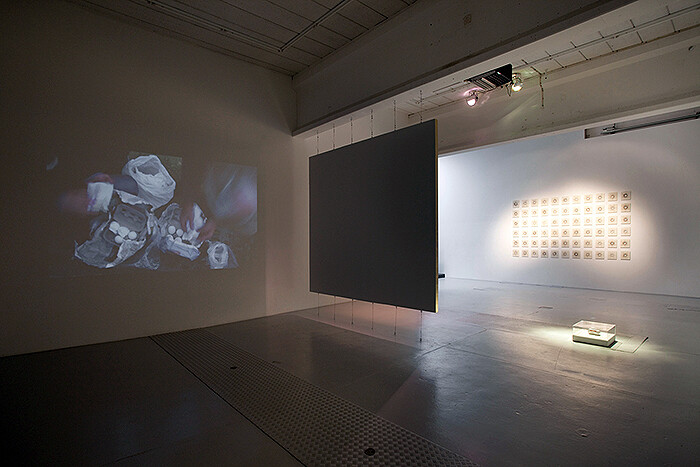

This is also clear in the work Pergamon (A Place in Things) (2014), which consists of approximately 100 different fluorescent light bulbs, some stolen from the Pergamon Museum in Berlin. Displayed rhythmically and precisely on a square pedestal, they are presented like “valuables” and protected by a barrier. It is not so much that they are displayed as fascinating luminous objects (they are not plugged in), but rather the act of taking them from the museum—either with or without permission—metaphorically “turns off the light of knowledge” (i.e. the European Enlightenment). When viewing this work, one comes away with an image of the Pergamon Altar situated in a dark museum hall, as well as a questioning of what role can art and culture play in the political resistance against totalitarian systems. Lagomarsino hints here at German-born writer and artist Peter Weiss’s 1975–81 Die Ästhetik des Widerstands [The Aesthetics of Resistance].1 In this three-part novel, Weiss describes how art could strengthen and sharpen the political consciousness of people dedicated to anti-fascism. As the main protagonists of the novel contemplate the Pergamon Altar, the face of divinity is revealed as the face of sovereignty, and thus, as a misdirection of history.

When writing on art, one is always inclined to include a biographical note on the artist. However, Lagomarsino’s biography is intellectually and ironically performed in almost all of the works of the show (especially with his idiosyncratic acting). In 2009 und 2010, as part of CAPACETE, a residency program in São Paulo und Rio de Janeiro, he made his “home” in Brazil—and established himself as part of a transnational generation of young artists (he was nominated, for example, for the PinchukArtCentre’s Future Generation Art Prize in 2011). But rather than ascribe connections between his life and art, we can keep up the suspense, and let Lagomarsino have the final word. Namely, with his own Untitled (Self portrait) (2011), which intertwines his personal biography with the construction of Europe and the Americas. Cleverly, the artist places a paper box atop a cloth napkin which are respectively imprinted with ethnicized restaurant labels: “Euroville” and “Hispano.”

Peter Weiss, Die Ästhetik des Widerstands, Vol. 1–3 (Frankfurt: Suhrkamp, 1975, 1978, 1981).