When was the last time you walked into a painting exhibition at a commercial gallery and saw something truly politically radical? The answer for many in the West is likely “rarely, if ever,” especially if we’re referring to West Chelsea or London’s Mayfair. “The Un-Officials | Art Before 85” highlights the practice of artists working in post-Reform China in what appear to be conservative, pastiche styles. These artists were active amidst the denouement of the prohibitive Cultural Revolution, as early as 1973, and through the period of détente between intellectuals and political officials through 1985, marked by a moderately less authoritarian Chinese government led by Deng Xiaoping after Chairman Mao’s death in 1976.

“The Un-Officials” focuses on the efforts of two groups: the Wuming Painting Society (wuming means “no name,” or “anonymous”), founded in 1973, and the Xingxing (“Stars”) Group, founded in 1979. The self-taught artists comprising these two groups rejected state-sanctioned Socialist Realism, instead teaching themselves how to paint in banned western styles while attempting to dodge government surveillance; many of these groups’ members were jailed for insurrection or sent to the countryside for “reeducation.” The styles these artists painted in, often anachronistic, ranged from Action Painting to American Abstract Expressionism, and all the way back to Impressionism. While the Wuming and Stars artists adopted these outdated western styles because their illegality provided an aesthetic rhetoric of political resistance, they were also utilized because, due to the halting of public intellectual activity amidst the Great Leap Forward and Cultural Revolution, China did not develop the roots of modernism that had been laid amidst and after the New Culture Movement of the mid-1910s and 1920s.

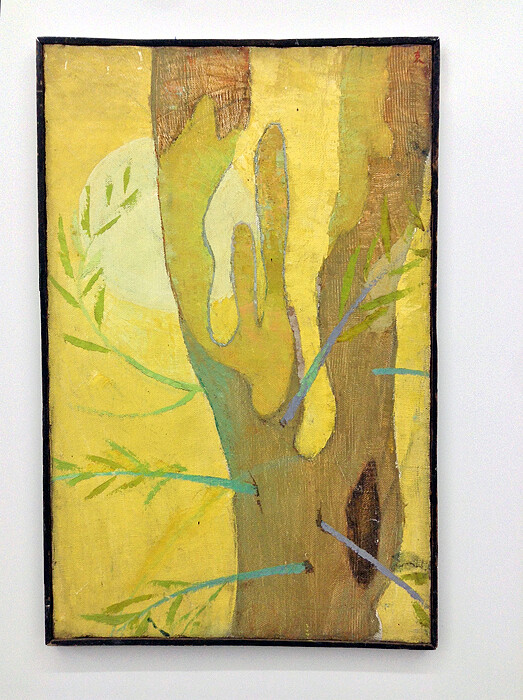

The less politically inclined group of the two, the Wuming Painting Society, produced landscapes en plein air, emulating Impressionist and Fauvist styles. Though heterogeneous in content, the Wuming’s paintings often focused upon the subconscious thoughts and feelings of its maker—a politically charged act in an era of extreme authoritarianism mandating national homogeny via the total compliance of its citizens. The standout painting of the exhibition, Life (1975) by Wuming group outlier Feng Guodong, depicts a melting, yolky yellow tree whose branches appear to be piercing its trunk, as if shot by an outsider.

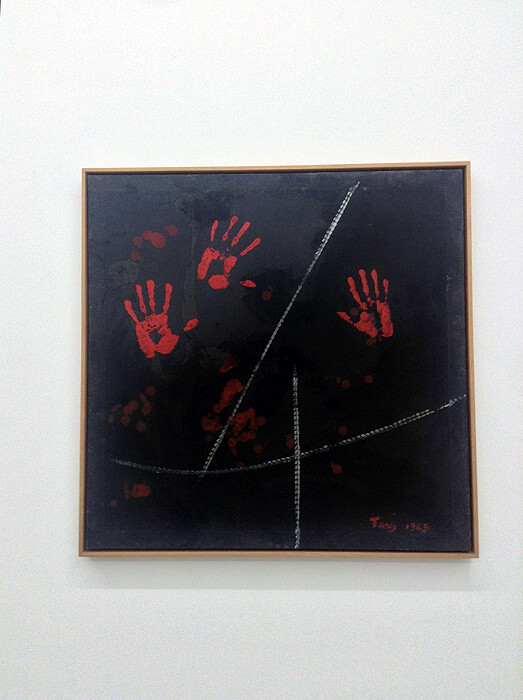

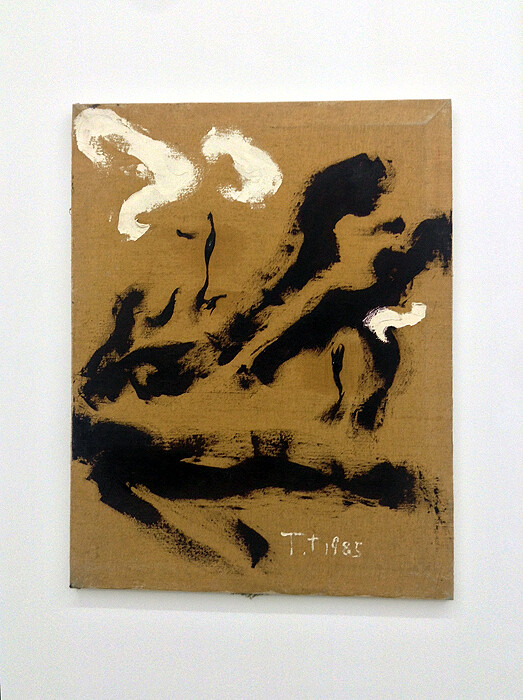

The Stars Group used public space to brazenly confront the Chinese government’s imperious policies, installing their paintings in well-populated parks and even forming a protest in Beijing’s city center. This desire to subconsciously “break free” can be seen in Stars Group member Tang Pinggang’s untitled painting from 1985, in which red hands are stamped on and claw at a black canvas. “It never occurred to us that what we were doing with the Wuming Group and then the Stars Group was anything to write home about,” reflects Stars Group founder Li Shaung, who has since expatriated to Paris. “I’ve labored, cried, laughed, been in prison, despaired, triumphed, and in the end—quite naturally and unwittingly—we laid the cornerstone for the revival of art in the 1970s.”1 Her curious painting, Thinking (1981), depicts an isolated, genderless figure sitting in a forest of limbs wrestling each other, and recalls the melancholic landscapes of American painter Charles Burchfield.

Other than the incredible feat of pulling together such arcane historical works, not all is remarkable at Boers-Li. As can be expected from paintings produced in transit and under intense scrutiny, the works in “The Un-Officials” are aesthetically uneven in quality, and, by definition, pastiche. Further, the exhibition has little systematized logic in its installation, and individual works are not labeled with any historical background or cataloging information. This decidedly non-pedagogical approach seems like a missed opportunity to shed light on a vitally important moment in Chinese art history about which we still know little—though to be fair, pedagogy is not the prerogative of a commercial gallery. Many of the artists associated with Wuming and Stars eventually expatriated under Deng’s “supreme leadership” (1978–1992) due to growing frustration with unfair imprisonment and the lack of free expression in China; others remaining in China have experienced variable success in the commercial art world.

Given that Chinese art has continued to change so drastically, especially since the privatization and bloating of the Chinese art market in 1992—which has provided much of the West’s elementary-at-best knowledge of Chinese art—it seems all the more incumbent to look back at a time in which art meant everything, and the market nothing.

As quoted in Simon Zhou, “In the Beginning,” Time Out Beijing, no. 113 (March 2014): 46–47.