An idyllic scene of Dionysian abandon: six naked bodies splash across the sun-flecked, crystalline surface of a lake, moving, one by one, in slow motion past the camera’s lens. They are all smiling, healthy, happy, vital, and young. This is the opening sequence of Water Light/Water Needle (Lake Mahwah, NJ) (1966), Carolee Schneemann’s 11:13-minute, 16mm film, now presented as a video diptych on a single, large LCD flat screen.

The sequence carries many of Schneemann’s signature themes: collectivity; a shameless, guilt-free, pre-Edenic engagement with the body; and an embrace of pleasure and the liberatory possibilities of orgiastic energies. Depending on your stance in relation to such matters, the scene is an emphatic statement of ideas and intentions that you either embrace or reject. Institutionally speaking, it has largely been the latter. While her legendary status and influence on artists of all generations means Schneemann (born in 1939) continues to be a central canonical figure, it is shocking that “Water Light/Water Needle”—a modest collection of photographs, drawings, and a single video work currently on view at Hales Gallery—is her first solo exhibition in London.

That said, Schneemann’s status as a professional artist, with a bit of an outsider status, has served her well. From this standpoint, she has been able to pitch her unique oeuvre against dissenting voices from prevailing socio-cultural and art historical orthodoxies. From the 1950s until now, this included the inescapable shadow of male chauvinism; the dictatorial edicts of Greenbergian formalism; second-wave feminists uncomfortable with heterosexual display; the commodification of sex; and currently, the bloodless anti-anthropocentrism of object-oriented ontology. In fact, the exuberance and political directness of Schneemann’s practice—exemplified by her influential work Interior Scroll (1975)—stands in contradistinction to a certain post-conceptual asceticism that has become pervasive in an increasingly professionalized art world. As such, her work continues to bristle with an iconoclasm and revolutionary zeal that belies the New-Agey, hippyish idealism of its utopic surfaces.

In concrete terms, “Water Light/Water Needle” is an exhibition that revisits a live performance Schneemann first conceived while visiting the 32nd Venice Biennale of 1964. It was staged at St. Mark’s Church-in-the-Bowery, New York in 1966 and then filmed on a grand estate in the township of Mahwah, New Jersey later that year. In order to recreate the sensation of weightlessness she experienced while walking through Venice, Schneemaan devised Water Light/Water Needle as a group performance, in which male and female participants would move and interact on a suspended rope apparatus. The muted, spotlit display at Hales, then, is comprised of documentation in three parts: drawings, photographs, and a video diptych.

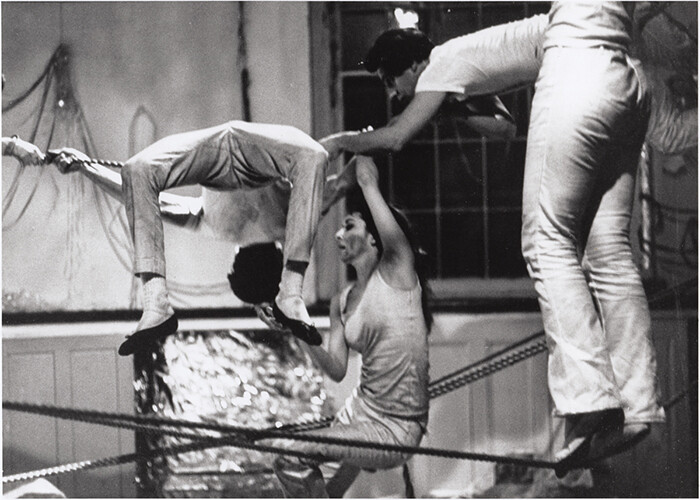

Along the gallery’s right-hand wall hangs a collection of seven watercolor diagrams and prospective performance sketches. Each work attempts to register the energy of a live performance; although they are figurative illustrations, they carry an intuitive, somewhat impulsive and frequently entropic line. Nearby is a selection of large, black-and-white framed photographs documenting the original performance in St. Mark’s Church, upon which Schneemann has applied colored acrylic paint. In Water Light /Water Needle III (1966–2014), the performers stand between ropes in midair, while in Water Light/Water Needle II, I, and IV (all 1966–2014), bodies are coupled in an interlocked state. The solemnity of the documentary-style, monochrome print lends a certain historical weight to these works, which is offset by the lighter patches of blue and yellow paint.

While these works in the exhibition invite a kind of anecdotal hermeneutic—in which interpretation is bound up with the retelling of contextual details that now function as a fairly nostalgic historical narrative—the question remains: why revisit a decades-old performance? An assessment of the facts suggests two possible reasons. Firstly, a number of seminal works by Schneemann—including Eye Body: 36 Transformative Actions (1963), Meat Joy (1964), and Fuses (1965)—have drowned out the art historical significance of the subtler Water Light/Water Needle, and so for many gallery visitors, the Hales display might register as a new discovery within her performative repertoire (albeit in documentary form). Secondly, the reception of her work has varied fairly radically with each decade, in step with contemporary shifts in critical discourse, thus mobilizing her practice into a state of perpetual activation. Granted, these are not the most revolutionary grounds for a new rehanging of her work, but Schneemann’s “Water Light/Water Needle” does succeed in lifting the vestiges of her larger practice out of archival stasis. Ultimately, the exhibition is a respectable, if unsurprising, turn by one of the most important artists of the twentieth century, making a strong case for the immediate development of a full-fledged retrospective.