Braco Dimitrijević’s current exhibition at MOT International offers a careful selection of early works by this Paris-based, Sarajevo-born pioneer of Conceptual art. The show’s title, “Early London Years,” refers to the period from 1971 to 1973 when the artist lived there, although a number works produced in other cities like New York and Zagreb between 1968 and 1988 are also on view. Casual Passer-By I Met at 1.14pm, London 1978, for example, is part of one of Dimitrijević’s most celebrated “Casual Passer-By” series (1969–ongoing), in which he photographed anonymous city dwellers and, after obtaining permission from the local authorities, printed the portraits on huge billboards in a key public space. At MOT International, a framed certificate and a picture serve to document one such action, which was installed in the Leicester Square tube station. Although this was notable within the context of a city like London, there have been more confrontational iterations, including when Dimitrijević hung several billboards in 1971 with anonymous faces in the public squares of Zagreb—sites which were usually reserved for the honoring of figures like Marshal Josip Broz Tito and other high ranking officials.

John Foster (1972) is another twist on the “Casual Passers-by” project; Dimitrijević installed a memorial marble plaque of his sitter on the façade of a house as is typical of famous historical figures. About Two Artists (Leonardo – Evans) (1988), a third variation on the theme, is a showdown of two marble busts, one bearing the effigy of Leonardo da Vinci and the other with the semblance of another John Doe who, as a framed text certificate duly informs us, was also painter, but sank into obscurity. Dimitrijević returns time and again to the issue of celebrity, questioning the reasons why some names are written into history, while the talents of many unknown men and women go unnoticed. With its insistent vindication of the everyday man, it comes as no surprise that late Swiss curator Harald Szeeman included an iteration of “Casual Passers-By” in the “Individual Mythologies” section of his 1972 Documenta 5.

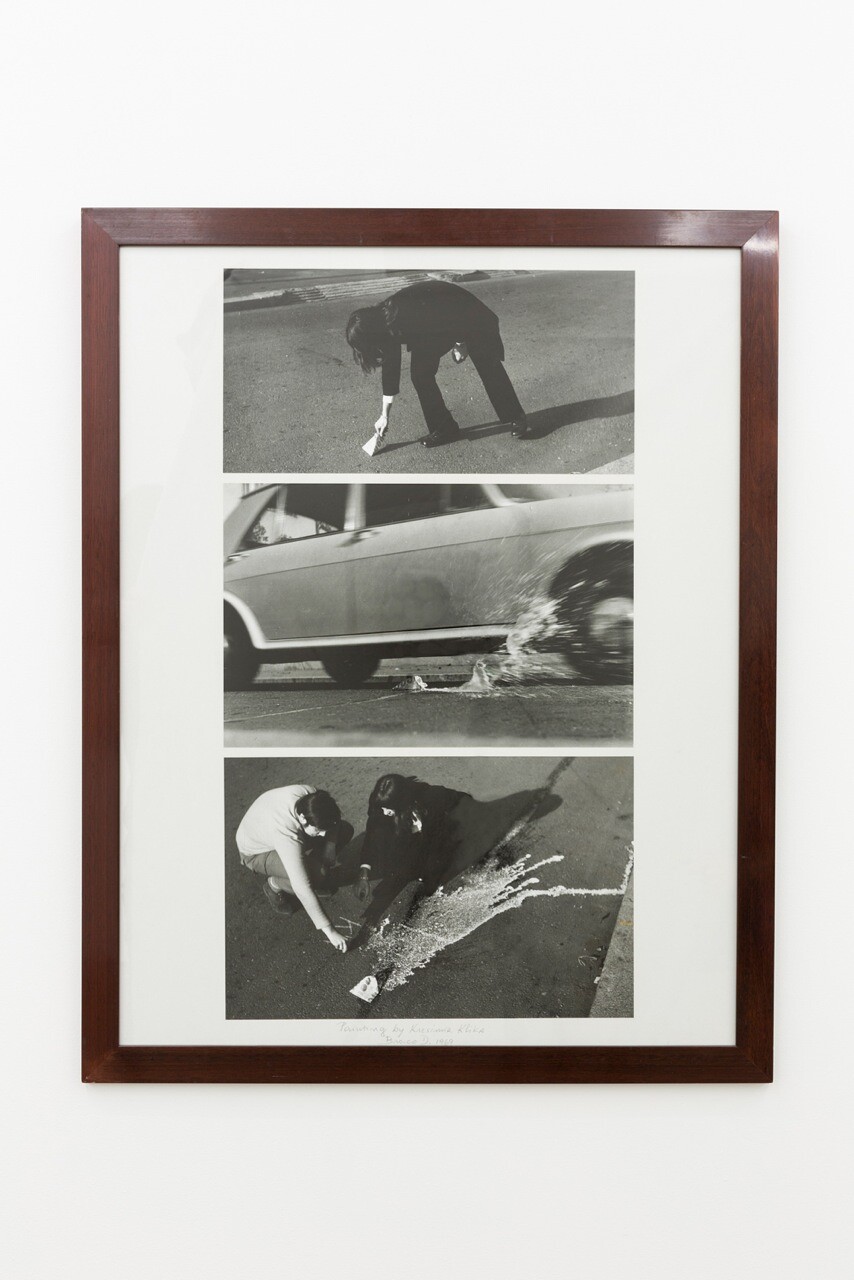

When a 23-year-old Dimitrijević enrolled in the postgraduate course in the sculpture department at St. Martin’s School of Art in London in 1971, he had already accumulated substantial artistic experience. As the son of Vojo Dimitrijević, a celebrated painter from the former Yugoslavia, he grew up amongst his father’s brushes and canvases, and began exhibiting his work at the age of ten. Wanting to break with traditions (both familial and artistic), he gave up painting soon after and started a practice based on urban interventions. His Accidental Sculpture, Accidental Drawing (both works 1968) and Painting by Krešimir Klinka (1969) are early examples, and are perhaps the most delicate and nuanced works in this exhibition. Dimitrijević would leave materials on the streets and wait for some chance occurrence to turn them into contingent works of art, from a gust of wind turning plaster powder into an ephemeral sculpture to a tram slicing a sheet of paper in two.

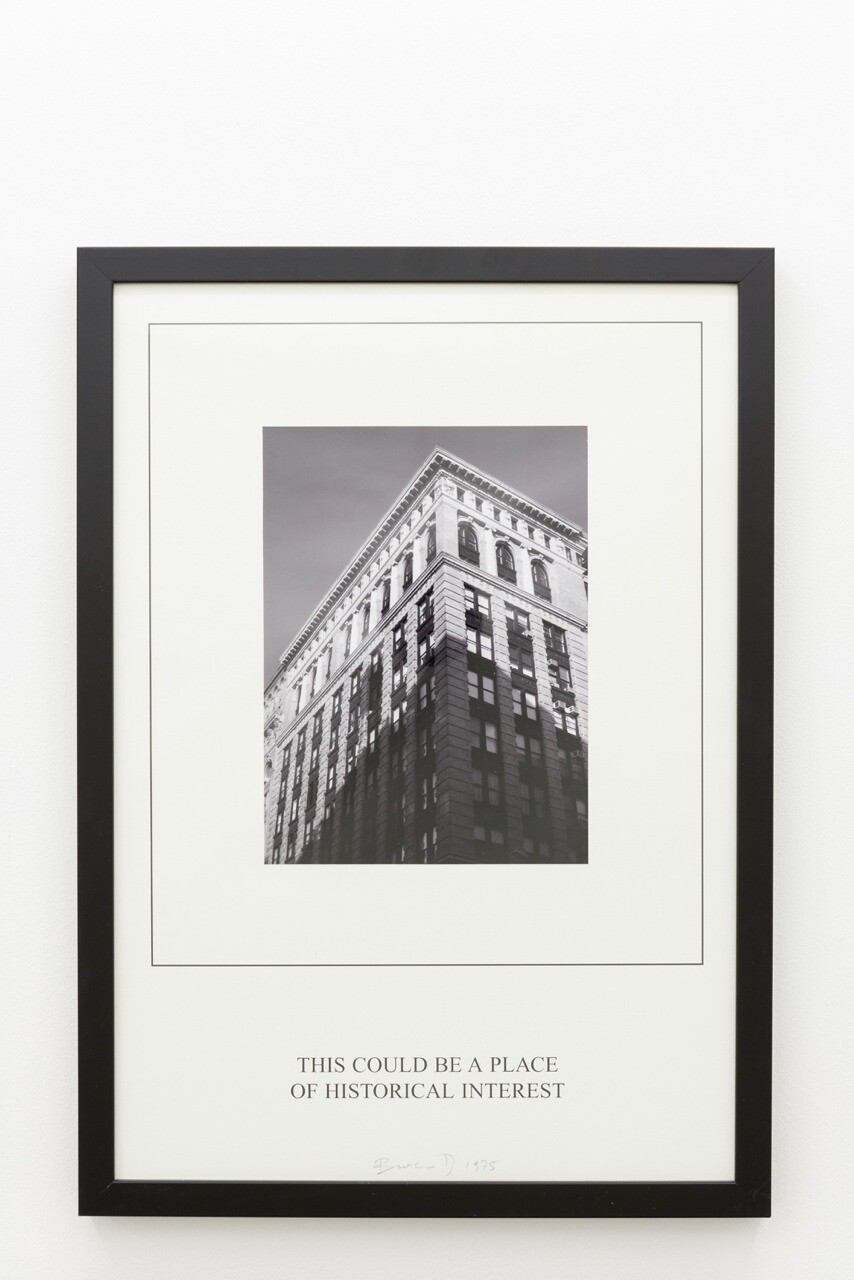

With the city streets as backgrounds, these interventions in public spaces bring to mind the actions of George Maciunas, or other works by less prescriptive conceptualists like Vito Acconci’s Following Piece (1969) or Ewa Partum’s Aktive Poesie [Active Poetry] (1971–73), which also relied in the interaction of the artists with participants to generate meaning. And while these works critique the monolithic systems of value and authorship typically associated with the production of art and history, they make their point in a much more playful and understated manner than coeval series like Dimitrijević’s “This could be a place of historical importance” (1971–ongoing), in which marble plaques bearing this message were installed in random pedestrian locations.

Overall, Dimitrijević’s oeuvre appears somehow paradoxical: he rejects both history as a false construct and fame as an invalid system of valuation, but his constant engagement of these issues by replicating their official language (through his use of certificates, plaques, billboards) reveals a fascination with them as representing aspirational, or at least inescapable, taxonomies of existence. This echoes the contradictions of Conceptual art or even institutional critique, which rejected formalism and the commodification of the art object, but quickly became institutionalized (and commodified) styles themselves, opening up the age-old question of how effective a cultural critique can be that reproduces the same codes it targets, be it bureaucracy, history, or the visual language of corporations. Still a predominant strategy of much critical art, I sometimes wonder whether resistance might be better prompted by an art that reimagines reality, instead of mimicking it.