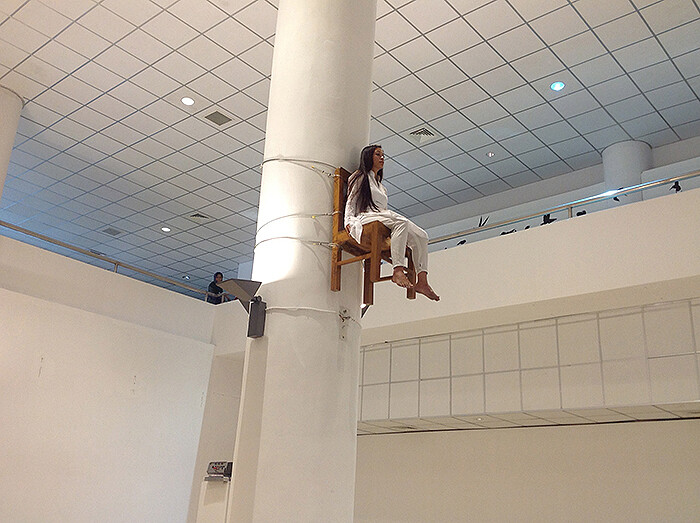

A young woman hovers about one story above ground, secured to a central column in the Bangladesh Shilpakala Academy (National Academy of Fine and Performing Arts) in Dhaka. As part of her performance Sat on a Chair (2014), artist Yasmin Jahan Nupur remains trapped and uncannily motionless over the space of three hours. In direct contrast, beneath her is a crowd of restive art-goers who ricochet the vibe of the heaving metropolis beyond the precincts of the academy building, playing host to the second edition of the Dhaka Art Summit, a three-day arts festival initiated and produced by the Samdani Art Foundation.

The event drew a wide range of local and international audiences—many flocking in from the commercial India Art Fair, which took place in Delhi from January 30–February 2, 2014. Since the Indian capital has remained the prime cultural gateway for much of the international art world claiming an interest in South Asia so far, it was refreshing to experience a de-centralized engagement with the arts in Bangladesh’s capital city, Dhaka, featuring artists and institutions from Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and other parts of the region, who have rarely had the occasion to physically gather as part of the same platform in such large numbers.

Across the summit’s fourteen different solo projects curated by its artistic director, Diana Campbell Betancourt, one noticed multivalent expressions of refusal. The preview day of the summit in Dhaka coincided with a countrywide, dawn-to-dusk strike (called Hartal, in local parlance). The discordant rhythms of political shutdown resonated with Raqs Media Collective’s citywide public art project Meanwhile Elsewhere (2014), which erected commissioned road-signs and billboards throughout the city, featuring clock faces that strike Bengali word-pairs dialogically instead of telling time—transforming the urban commute into a kind of emotional architecture. Mithu Sen’s Batil Kobitaboli [Poems Declined] (2014) assembled the rejected verses of about 40 Bangladeshi poets in a single, handmade book. Embossed in gold and with a leather-bound spine, the book, nearly two feet in height, stood out as both ephemeral monument and publishing object.

In Bangladesh-born and London-based Runa Islam’s 16mm film Untitled (After the Hunt) (2008), an out-of-focus diminutive photograph belonging to the artist’s grandfather resisted the camera gaze. In so doing, it gestured to the unstable character of memory, the limits of image construction, and the diasporic condition as a form of elemental abstraction. Nearby, Shilpa Gupta’s multi-part installation Untitled (2014) examined the fragmentation of ancestral lands and communities that have persisted across the Indo-Bangladeshi enclaves (known as chitmahals) in the post-partition era. Primed with a disclaimer, Naeem Mohaiemen’s single-issue newspaper project Shokol Choritro Kalponic [All Characters Are Imaginary] (2014) instilled exaggerated and amusing accounts within the conventional terrain of daily news. As an imaginative address, the artist cultivates these utopian scenes as if the ultra left had come to power in 1970s Bangladesh.

The summit also included three additional discursive events and programming. Alongside the performance and experimental film program conceived by artist-curator Mahbubur Rahman, a series of moderated talks brought together museum curators, artists, biennial directors, and heads of institutions. Unlike Rahman’s thoughtfully framed, time-based program, most panelists sped through dry presentations on acquisition policy, infrastructure building, and strategic network building in the region. In parallel, the South Asia Network for the Arts (SANA) book launch with members of the Triangle Network—including Gasworks (United Kingdom), Britto Arts Trust (Bangladesh), KHOJ International Artists’ Association (India), Vasl Artists’ Collective (Pakistan), and Theertha International Artists’ Collective (Sri Lanka)—reaffirmed the value of decade-long, independent collaborations across the politically splintered and publically under-resourced cultural scenes.

Among the gallery presentations at the summit, Mumbai’s Jhaveri Contemporary presented an unusual yet compelling trio: modernist artist-writer Anwar Jalal Shemza’s (1928–1985) abstract compositions that drew upon the geometric symbolism of Islamic architecture with the deft fluidity of Arabic calligraphy; Rasheed Aaereen’s meditations upon the grid; and Rana Begum’s quirky wall sculptures, which update the lexicon of Op-art and hard-edge painting. Together, these inter-generational diasporic practices revealed poignant phenomenological readings of space, the built environment, and Minimalism. At New Delhi’s LATITUDE 28 booth, Anindita Dutta’s Life Line I (2010) exquisitely brought together performance and drawing practice through the substance of wet clay. At the very end, in Delhi Art Gallery’s booth, one caught a series of rare linocut and ink on paper works by radical modernist Chittaprosad Bhattacharya (1915–1978), known for his emphatic portrayals of colonial rule as symbolic apparatus, popular struggles, and the Bengal Famine of 1943.

Among four curated exhibitions showcasing South Asian artists and photographers that were also part of the summit, curator Veeranganakumari Solanki’s “Citizens of Time” explored states of impermanence, exposure, and residue within urban living. Artist Riyas Komu’s video work Last Wall (2012–13), which follows the self-scripted movements of a fringe character in the artist’s neighborhood as he makes text-drawings on public walls, continued to haunt long after one saw it. On the upper floor, “B/Desh,” curated by Deepak Ananth, included striking works by Ayesha Sultana, winner of this year’s Samdani Art Award conferred in collaboration with Delfina Foundation. Her “Amnesia” series (2013) engaged the nature of forms as folds, shadow spaces, and dwellings.

After zigzagging through the Shilpakala Academy for two days, I finally managed to escape the main venue to visit BRITTO SPACE, which is run by the Britto Arts Trust—regarded as the most dynamic artist-led initiative of the country—and is now entering its twelfth year. Located amidst a dense weave of pharmacies, daily provision stores, and hardware outlets, the organization presented a group exhibition titled “Cross Casting,” premised upon the dynamics of gender difference and queer sexualities within the local context. In a small room of the gallery-cum-residency space, artist and co-founder Tayeba Begum Lipi’s diptych film installation Home (2014) drew upon her extended conversations with a transgender protagonist, revealing sublime correspondences between rebellious desire, death, and life as art.

Back at the Dhaka Art Summit, I recall returning to Nikhil Chopra’s eight-hour performance Blackening VI (2014), in which the artist treated the surrounding space as an itinerant landscape mapped with black shoe polish and paint. Throughout the day his renderings of self-portraiture met with the polemical poses of collective history. And therefore, rather intuitively, it seems appropriate to conclude with Chopra’s work, which puts forth endurance as a means of personal agency. While it proves impossible to wager a comprehensive statement on the second Dhaka Art Summit, for now—and here supported through private funding—this event marks an attempt to strengthen “Southern” alliances by actively broadening the cultural field. Perhaps, it is only a matter of time before wider public recognition and participation reinforces this much-needed, cultural counter-balance to India’s current geopolitical role as the region’s “Big Brother” state.