The cornerstone of Isaac Julien’s new exhibition in London is PLAYTIME (2014), a seven-screen, high-definition video installation that features well-known actors James Franco, Maggie Cheung, and Mercedes Cabral, as well as Swiss auctioneer Simon de Pury. Set across three continents, the work follows a suite of characters—the Artist, the Hedge Fund Manager, the Auctioneer, the House Worker, the Art Dealer, and the Reporter—who each occupy distinct chapters. Introducing an episodic structure into the piece are Julien’s choice of locations—the cities of London, Reykjavik, and Dubai—which function allegorically; they were all selected because, it is argued, they are somehow uniquely defined by their relationship to capital.

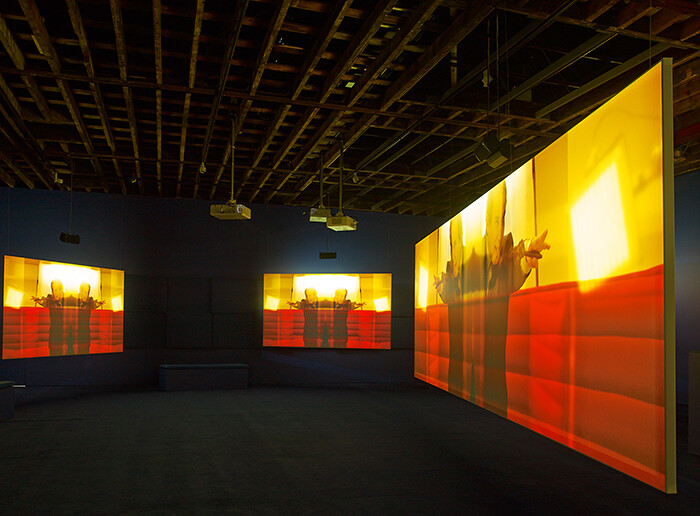

PLAYTIME operates much like an out-of-sync travelogue. It traces characters as they push and pull at the fragile building blocks that compose contemporary capitalist society. De Pury, playing himself, proffers the most captivating performance. He recounts, with a mixture of anguish and fervor, the adrenaline and subsequent depression that consumes him before and after an auction. Julien’s camera corners de Pury—so close that we can feel him sweat and pulse—and his figure splits across the large central screen at the same time that it is mirrored, his image becoming a doppelgänger of himself. Could this be an allusion to the dual personalities (Good and Evil) that one must hold in order to adapt to the freewheeling marketplace?

Elsewhere, we are transported—whizzing speedily through endless corridors and past large-scale computer servers—before we are swept through the beaming metropoles of central London and Dubai, as well as through an unembellished house in Iceland. The mise-en-scène is often bare even when it is intended to be luxurious. Stark interiors create a sense of temporal impermanence—as if the characters can waltz and disappear across time zones, teleporting themselves to the next financial opportunity.

For the most part, each of the characters are isolated from other people—their singular pursuit being a monetary one. A moralistic tone underpins much of their portrayal. In one scene, the Hedge Fund Manager sits with an advisor placing bets on whether a colleague is wearing boxer shorts or briefs. Franco, the Art Dealer, walks viewers through a series of iconic artworks—elaborating upon them in purely crass financial terms, stripping them not only of their hermeneutic agency, but also their relationship to human subjectivity.

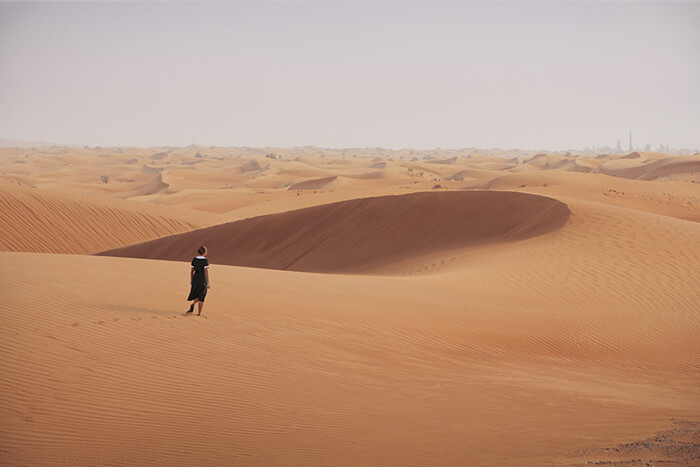

Isolation is felt most dramatically in the case of the House Worker, a striking Filipina maid played by Cabral who is trapped in a domestic household in downtown Dubai. However, it is here that Julien makes his most unfortunate misstep. The House Worker wears a maid’s outfit that looks like something out of British period film and her overly done appearance is unlike anything I have seen in the Gulf. While a generic Arabic song howls in the background, the maid stares out at sci-fi skyscrapers from an immaculate apartment that looks completely uninhabited. Alone, she complains of her oppression and longing for her family in the Philippines. Soon, we see her teleported from the apartment to a sand dune in the Arabian Desert into a scene that could resemble a tourism campaign video. It is unclear whether these sequences are intended to be ironic. Nevertheless, they induce one thing: a sense of Arab kitsch—a view of the Arab world told through mediated, distanced eyes. Indeed, this scene differs little from the innumerable portrayals of Arab sites to be found in hegemonic culture, where the men are abstract, oppressive figures, the women forced into labor, and the visual and sonic tapestry is one that evokes Orientalism.

The installation is further complicated by Julien’s refusal to imbricate his own recent large-scale, moving-image practice into the work’s central narrative. Certainly, one could argue that Julien’s own work could at times be seen to willingly participate in the very system he perhaps attempts to critique. After all, he left the world of independent cinema two decades ago, and today participates much more frequently in the commodity-driven art world. He is represented by big-name galleries and is arguably one of a select few responsible for turning video art into a kind of marketable object; his large, sumptuous screens are for many in the cultural sector prohibitively expensive to acquire and to exhibit. This raises the interesting question—how are such works sold, editioned, and distributed globally?

Downstairs on the gallery’s first floor, Julien presents a two-channel video called KAPITAL (2014), which, according to the gallery press release, is intended to be PLAYTIME’s “intellectual framework.” The work is a video recording of a conversation between the artist and noted social theorist and Marxist scholar David Harvey at London’s Hayward Gallery. As my gaze started flitting between the two screens, I considered why such a conversation could not exist comfortably on a single screen. Has the artist unknowingly been subsumed by a desire for excess? Could this documentation be merely an attempt at self-portraiture?

Passively watching this conversation, I realized that the work’s shortcoming may well be in the artist’s own introspection, which took precedence over his direct engagement with the viewer. If Julien were to make an effort to carve out a space for the audience to speak more generally, then the “PLAYTIME” exhibition on the whole may have been a much more engaging space to discuss the urgent issues surrounding global capitalism.