In the cosmos of art collecting, there are few private exhibitors as closely associated with a place (Mexico City) and an industry (juice products) as Fundación Jumex Arte Contemporáneo. The thousand-and-one guests who descended on D.F. this past weekend for the lavish opening of collector Eugenio López’s David Chipperfield-designed Museo Jumex in the uptown neighborhood of Polanco were in for a very different experience than trekking ninety minutes (in good traffic) from the city center to the grounds of the Jumex factory in Ecatepec, where until now the Fundación’s galleries had been headquartered. The exhibition space at the factory still exists; a retrospective exhibition of the Danish collective SUPERFLEX is currently on view. But now the contemporary art collection, Colección Jumex—assumed to be Latin America’s largest—has put down roots in central D.F., rearranging the cultural geography of the Western Hemisphere’s most populous capital overnight.

Mexico City is blessed with a number of great contemporary art museums—Museo Tamayo, whether or not it ever expands, in Chapultepec Park; Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo (MUAC) on the campus of the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM) in the south; smaller institutions like Museo Experimental El Eco on Reforma and the non-profit Sala de Arte Público Siqueiros (SAPS) in Polanco—however, as a civic point of interest and a feat of twenty-first century architectural showmanship, it’s hard to rival this corner of Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra, where the Museo Jumex now sits opposite Carlos Slim’s eccentrically hubristic Museo Soumaya, which opened in 2011. Indeed, probably the best sight provided by Lopez’s new museum this weekend was the picture of the Soumaya, in all its tiled mushroom cloud grandiosity, framed by the outlook of the Jumex’s first floor terrace, where the public programs were held (a roundtable on the role of the private museum, a talk between Hans Ulrich Obrist and the architect, and a performative lunch). The city block is like a kernel of an Arabian upstart in the New World: two of the most moneyed private museums anywhere, sprouted beside one another on a commercial thoroughfare en route to becoming a miracle mile.

With two floors of proper galleries, the malleable first story, a basement bookstore, and the usual public spaces like a ground floor café and a promenade for outdoor installations (the first of which is local artist Damián Ortega’s year-long exhibition “Cosmogonía doméstica,” an ornamental arrangement of tables, chairs, and other components of a dinner setting that are kilted and seemingly levitated while simultaneously attached to the ground by angled piping), Museo Jumex is a real museum. It is not dissimilar in size from New York’s New Museum—not that the New Museum is ever criticized for being too roomy, nor that Mexican buildings are known to skew small. A creamy travertine skins its exterior and floors, a compromise between the transnational code of the white cube and a local design ethos that encourages raw, weighty materials.

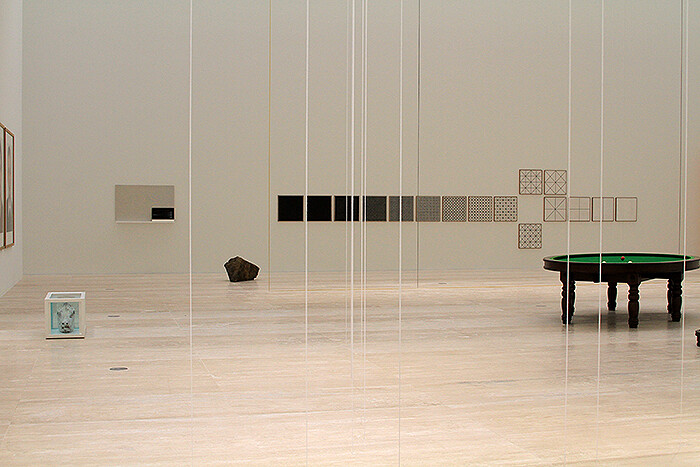

The heart of the inaugural exhibitions (on view until February 9, 2014) is the third-floor show organized by Patrick Charpenel, Fundación Jumex’s director. His wall text invokes a theory borrowed from quantum physics of parallel realities, or, in this case, of simultaneous realities occupying a single space and time. Titled “Un Lugar en Dos Dimensiones: una selección de Colección Jumex + Fred Sandback” (“A Place in Two Dimensions: A Selection from Colección Jumex + Fred Sandback”), the overlapping realities declared here are that of the menagerie of works culled from Jumex’s permanent collection, and of an interstitial exhibition of seven sculptures by Sandback, an American minimalist.

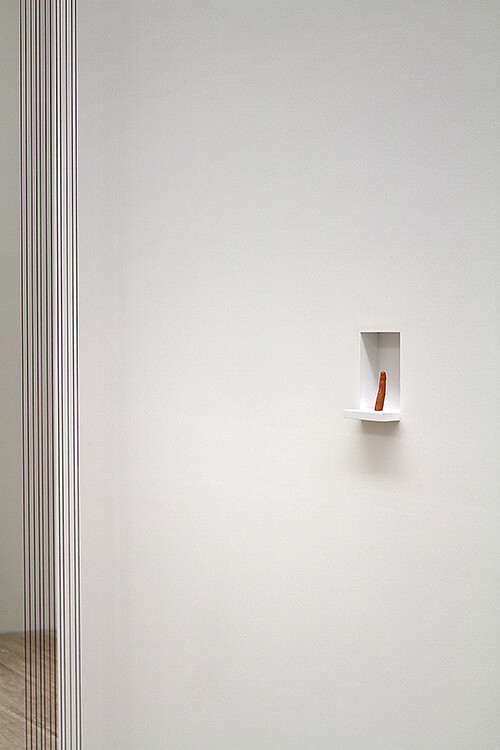

There are occasional moments of synergy between the two, such as with the twinned verticality of strands of purple yarn stretching to the ceiling (Sandback’s Untitled, 1967) beside a lone, erect digit by Sarah Lucas, Receptacle of Lurid Things (1991), or when they scramble one another, as with the view of the largest room, which, from most vantages, one must spy through an irregular grove of white yarn. Potentially the most dynamic pairing is between the eighty-two Fischli and Weiss photographs that make up their “Equilibres” series—a catalog of tautly balanced household compositions shot between 1984–86, from assemblies of wine bottles, vegetables, and kitchen accouterments to larger constellations involving ironing boards, bicycles, and violins—and two Sandbacks on the opposite side of the hallway: a recent sculptural study whose two blue stings score the floor before ascending in parallel, and another, Untitled (Mikado) from 2001, with five intersecting black diagonals that describe a theater of lines on the wall. Unfortunately, their installation nestled along a narrow walkway makes it difficult to take in the three artworks as a conversation, and nearly impossible to represent them together for posterity.

“Un Lugar…” contains many more than two realities, however. The conceit of parallel universes is also a good justification for the curatorial schizophrenia inherent to producing a survey touting collection highlights. A couple dozen paces in and the show feels like a hunting lodge full of trophies: Urs Fischer, Richard Prince, and Maurizio Cattelan; Carl Andre, Donald Judd, and Jasper Johns; Damien Hirst’s bull’s head, pickled basketballs by Jeff Koons; Andy Warhol. With the right budget at a big fair, you could pick something up from potentially every artist in the show in one afternoon. Most of the artists on view are white men from Europe and the United States. Of course, this problem might occur at any contemporary museum. But if Jumex’s first show can be read as any kind of charter, the institution seems to be leveraging its sizeable, international holdings not to break the status quo, but to bulwark it. Locally, this agenda isn’t necessarily redundant, but from an international perspective it doesn’t inspire new energy.

A little less than a quarter of the artists were born or live in Latin America. Some of their works are the most unique here. An unusual diptych of Surrealist paintings by Francis Alÿs depicts a suited man’s back twice, with his face obscured once by artificially wavy blonde hair, Man with Wig (1994–96), and again by naturally wavy blonde hair. Gabriel Kuri’s Sin título (A la brevedad posible) (1999), a faux hunk of iron engraved with the words “A la brevedad posible” (“As soon as possible”) offers a simple juxtaposition with the chicer stone that abounds throughout the building. In a standout piece by Daniel Guzmán, La Cuenta de los Días (“The Count of the Days”) (2009), several meters of shelving is stocked with cut-out, black-and-white images from daily newspapers, with depictions ranging from Obama and tarts to slain bodies and drugs prepared for destruction. Sculptural flourishes, like a skull and antlers encrusted in rainbow beads or other artisanal curiosities, catalyze the display as a psychological taxonomy of Mexico’s fraught recent histories.

Wandering down into the parking garage, one encounters an unannounced pop-up exhibition organized by Paris-based adviser Patricia Marshall, “Confusion in the Vault.” The title couldn’t be more apt as the nice moments do instill a sense of subterranean disorientation—what could be a better setting for Mike Kelley’s famous horse pantomime from Day is Done (2005)?—and the rest is cause for head scratching. Some corridors somehow feel overhung (with some really messy sculptures), and others are forlorn, occupied only by the most rote, spooky standbys, like Paul McCarthy’s large photos of kitschy, weathered condiments.

Overall, the most promising section of the new Museo Jumex might be the second floor James Lee Byars exhibition co-curated by the Fundación’s Magalí Arriola and MoMA PS1’s Peter Eleey. If Jumex is going to regularly avail its resources to producing travelling collaborations with major, non-profit institutions, this is a mutually beneficial way for a private collection to broaden its resonance. The show is called “James Lee Byars: 1/2 an Autobiography” (on view till April 13, 2014) and pivots on a poetic, self-reflexive research undertaken by Byars at the statistical midpoint of his life, age thirty-seven. There’s a recursive nature to the works included: a gumball-sized golden orb on black tissue paper in a vitrine of correspondence and works on paper that reappears forty times larger, positioned in a scalene corner of the building painted black. There is another tiny gold ball under a massive bell jar atop a gilded Corinthian column, and a gold throne posted in a room billowing with red fabric. There is a mythological grandeur to the materials and theatricality of Byars’s works—indeed much of the ephemera here comes from costumes and performances—which at first seems to have little in common with Mexico. The four golden, towering, Teotihuacan-inspired stairways decorating the military complex transformed into an opulent Mark Ronson concert on a Saturday were a reminder of the universality of ancient materials that still hold narrative sway today.

Maybe the autobiographical Byars show is part-metonym for its patron Mr. López, who like the artist is something of an inscrutable figure. He is a very shy man, who was barely seen at any of his extravagant festivities this weekend and has amassed a prolific collection of art that will speak for him in perpetuity—now only a short walk from the subway.