None of these have titles.

I’d like to christen them instead with shifty poems, smoky strings of musical words, or better, give each a dull, quotidian name, culled from tombstones and television shows, like Doris or Louise, Fred or George. These are not the first things to live untitled. Everyday beauties, inexplicable happenstances caught in passing rarely get dubbed or designated either. The brown, seventy-year-old Ford truck with a wooden railroad tie for a bumper and license plate screwed cleanly in place. The single, red leather glove left on the bannister of the long outdoor staircase in the woods, a few drizzled drops gleaming in the bluish light of the overhead LED. The iridescent shimmer and hushed crinkle of a pink chiffon prom dress spotted under a bridge. Casual sightings: ephemeral, rare, nameless.

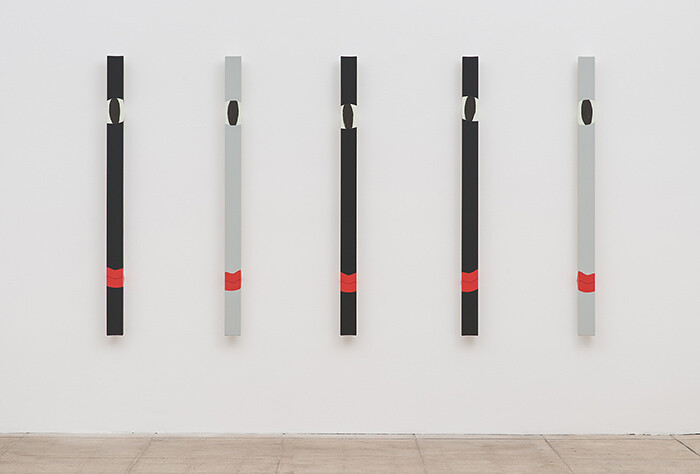

Dianna Molzan’s crafty ensemble here at Overduin and Kite is more people than things, a weird little gang of frames and canvases left unnamed by their creator; however, each and every one of them is quietly extraordinary. In the first room, a couple of cosmic crocodile eyes stare down an aged teenaged girl completely emptied out except for some still scrunching scrunchies, rendered soft black like a leather jacket that is more Fonz than Brando (Crayola named one of their crayons the exact same color, “Leather Jacket”). Up there in the center linger a quintet of eyeballed and pucker-lipped cigarette slim ladies, three black and two gray. A little bit goofy, those little mouths pout out some quiet joke hardly meant for a chortle or a guffaw, but simply a thin-lipped smile.

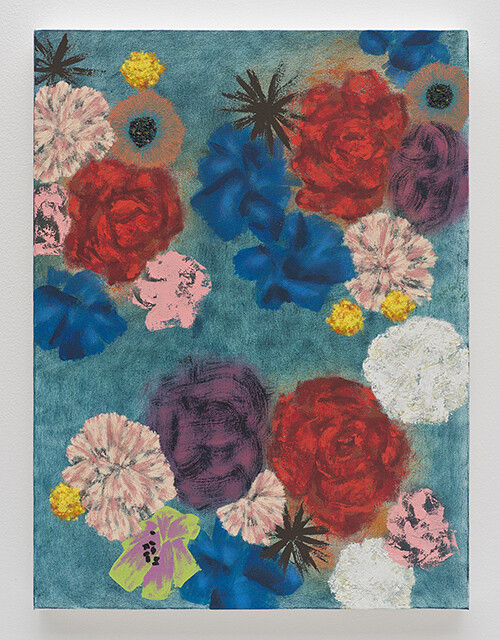

Around the corner, past a couple of real people tapping at a table, the next room hosts a party of pencil points and bite marks, smeary flowers, and nine fleshy gray cans strung from a rectangle of poplar. This party of patterns beams like prints on Pee-Chee folders and posters of Degrassi Junior High hanging in the background (from the design-forward art directors of Canadian TV). I keep thinking of this as a sleepover of teenage girls costumed in their mothers’ dresses, 1970s and 80s vintage specimens that they filched out of the mothballs and donned for some vaguely cheesy fun, worn with more glee than smirk. These are paintings with shoulder pads that are ill-fitting, but with nothing to prove aside from their own jaunty angles. Their Symbolist floral patterns might easily be cut into a sleek sheath for a wayward vamp or an evening frock for a Hausfrau, but I heard that the artist calls these flowery arrays “palette cleansers”—just a means to smear away old paint, rubbing out a brush into dreamy daubs.

These are really paintings after all, though anything can happen in painting. The simple rules are set out with simple materials. A rectangle on a wall. Canvas, wood, paint, maybe a few staples or nails to keep it all tacked in place. That’s a painting. This simple set, this frame for a picture is the picture. Everyone always forgets about the frames, the woven fabric, easily unraveled, or the wood of the stretcher bars cut—we’re too busy trying to soak in the picture to be dazzled by expressions of emotion or precise prowess. (Though we don’t crop out the frames of paintings in photographs anymore, now do we?) But once the stage is set, anything you fill into it will be read as a painting—whether it’s those nine cans hanging with canvas strings from naked wood, or an overlapping eight points of pastel-smeary points of color (the only primary colors to be found in a muddy wash of tertiary hues throughout). The colors and shapes replicate some bit of applied art. Molzan folds the pejoratively decorative (and distinctly unhip) patterns of the defanged abstractions meant for dresses or wallpaper, folders or bed sheets (the most distant, prodigal descendants of Kazimir Malevich) back into the fine art family with sly humor and elliptical grace.

Maybe their “brushiness” reflects soft-focus in the way that old illustrations and commercial abstractions used to—an effect all but handily murdered by Adobe Photoshop’s brush tool. Maybe I really don’t want to use the word “brushy,” but rather “breathy.” Yet, nary a breath exhales from those bright red lips—still and implacable.

Though each work is a character, they aren’t alive. They are just paintings, untitled. Maybe they’re not nameless, but unnameable. Better a flicker of color soundly skirting meaning than another example of words again chasing after elusive pictures.