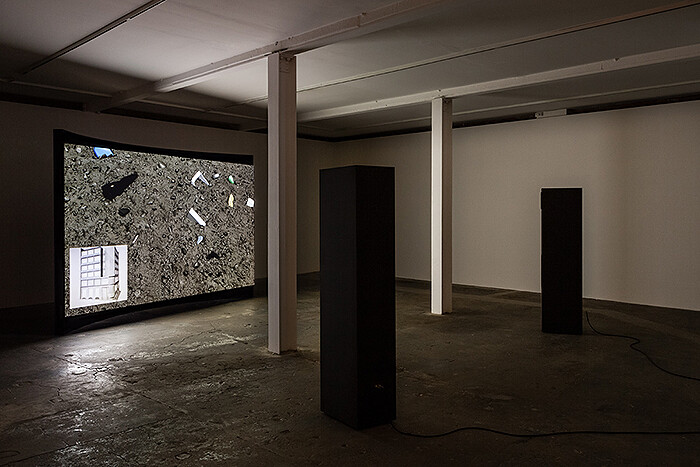

An aerial view, computer-generated, of a bleak, barren plain, improbably square in shape and bounded by undulating mountains, under a sunless grey sky. The view circles, then sweeps slowly down the speckled grey ground, gaining resolution as we begin to make out a terrain of grayish rocks, stones, gravel, and dust. Half submerged in this lifeless rubble, we catch sight of human artifacts: the spokes of alloy-wheel car tires, and other less distinct bits of bodywork—wing mirrors, fragments of fenders, wheel arches, and so on—shiny and brightly colored against the drab surroundings. Something that looks like the black slab of a computer keyboard, and a more indistinct, curved object that may be the chassis of a Mac Pro are also poking out of the dirt. Identical forms appear elsewhere as our view tracks around the plain. Then, without any hurry, the point-of-view slides up and away, back to a higher altitude, before the cycle begins again.

This video sequence loops on a big, freestanding, curved projection screen in the darkness of Hannah Sawtell’s solo show at Vilma Gold. A half-attentive, possibly uninformed viewer, who might not be familiar with Sawtell’s previous work, could probably still figure out that the artist has an interest in a world that is comprised of commodities—of both material industry (cars) and a virtual industry (keyboards, computers)—while she toys with the vision of the moment of their undoing. And if we were tuned in to the preoccupations of a current, vaguely Marxist critique of capitalism, we might wonder if what we were seeing was the aftermath of a world brought to its end in some final implosion of capitalist over-accumulation—or just some video game of it.

While we drift around the valley, there’s another frame in the lower left corner of the image, which displays a second computer-generated sequence. This time, it’s of an architectural rendering of a building, seen from various angles; a large, brick-and-glass block, six stories high, its ground floor on a slight slope, leading down to a curved corner. Again, without knowing all the details, the building’s style suggests European, interwar modernism and (with its high floors and big, square windows) some industrial function.

It turns out that this is a reconstruction of the architect Ernő Goldfinger’s 1946 design for the London offices and printing press of the Daily Worker, a historic newspaper of the British Communist Party. But without even knowing this, we might already sense a lot of melancholy in the video, as we contrast the nostalgic signifiers of a bygone era of twentieth-century industrial culture, which seems, in retrospect—with the apocalypse-from-now-on disillusionment of a dead world full of consumer junk that we find in the main sequence—so heroic and so clear in its goals and purpose.

But what can we conclude from this compare-and-contrast? What do we make of the ambient soundtrack of rhythmic clicks and static that issues from the two freestanding speakers aimed at the parabolic curve of the projection screen? Well, if we’re stuck, we could simply pick up a copy of Sawtell’s self-published newspaper, the RE PETITIONER broadsheet, stacked in the corner of the gallery. Designed like old socialist tabloids, with a black and red masthead and bold, sans-serif headlines, the articles offer a recognizable grab bag of contemporary, anti-capitalist, philosophic-political art writing, interlinking ideas of repetition, musical rhythm, and the capitalist tempo of production.

The RE PETITIONER (like “repetition,” see?) is, therefore, a little handbook of ideas for the video, which assembles a group of Sawtell’s friends and “co-workers” to produce a critical environment for the show. The theorizing found in the publication is a slightly overcooked brand of continental philosophy that re-re-reads Karl Marx’s Capital from the perspective of art, yet which seems unable to get beyond the influence of Gilles Deleuze, Michel Foucault, and Walter Benjamin. Contributor Robert Garnett’s testy polemic for rhythm as politics, for example, tells us that “rhythm has the capacity to produce a non-teleological futurity disarticulated from the present, from the inevitable, deadlocked Now of a Neo-Liberal Capitalism Realism,” while John Russell’s more enjoyably auto-parodic and playful “The Capitalisation of Death” mashes Freudian theory with Bruce Willis movies in order to figure out how repetition and death might contain the negation of continuity and punctuality required by capital.

This critical space offers plain enough points of reference for the video: the circularity and repetition; the attention to commodities; the complex, fugitive soundtrack; the image of a wasteland beyond the historical temporality of production; and the de-centered, collaborative aspect of the presentation. These are well-established tropes, and Satwell handles them deftly, but how you rate her work partly depends on whether or not you buy into her fairly legible rhetorical staging of these positions.

Noticeably, the broadsheet’s various writers mobilize the idea of circularity and repetition as a rejection of the present, which is itself apparently subordinated to the logic of capital. This rejection means looking for an “outside,” hence, the preoccupation, in the broadsheet’s contributions and in the video, with rhythmic circularity as an “outside” to linear, historic time. But the problem with these motifs is that they exclude any figure of human agency in the politics—and aesthetics—of the present. This is a common affliction of current art-critical leftism, which, under the enduring influence of post-structuralist antihumanism, rejects the legitimate active presence of human subjects, and posits the figure of the “inhuman” as the only agency of negation against capital.

But there is perhaps a twist in Sawtell’s video that doesn’t quite fit with this narrative. The building, superimposed on the larger sequence of the pre/post-historic wasteland, is of a factory of sorts, a place for the production of political ideology, at a time when working people’s actions had a direct effect on the world. The building stands in for the people who produce things, rather than for the desert of use(r)less commodities of the main sequence. This, then, is the politico-historical split in Sawtell’s video: the militant labor movements of the twentieth century were inspired by the vision of a society that would become more human through the harnessing and expanding of humanity’s productive powers. Today, by contrast, the left rejects the “consumer” society, seeing the expansion of industrial society’s production as only the symptom of capital’s inhuman drive to endless proliferation—its economic growth a headless monster leading to the destruction of the environment and civilization. What the left once fought for, it now rejects.

Sawtell’s video seems caught on the prongs of these incompatible accounts of human agency and productivity. Repetition—of the same old assumptions derived from the same old theorists—is what keeps the artistic left in its currently tedious, critical loop, railing against cultural consumption on the one hand, and stigmatizing the liberating potential of production on the other. Perhaps Sawtell still needs to decide what—or whose—side she’s on.