Galeria Stereo’s contribution to the third edition of Gallery Weekend, Warsaw’s pre-eminent art event, is a compact and elegant presentation of mostly sculptural, albeit intensely imagistic work by four artists: Nina Beier, Piotr Łakomy, Gizela Mickiewicz, and Michael E. Smith. It is also the first exhibition in the gallery’s stylish new space on Żelazna Street in Warsaw, having previously been based in Poznan.

The title of the show is inspired by a verse—“The new morals have altered the original data.”— from “The New Spirit,” a 1972 poem by John Ashbery. The original collection, Three Poems, in which the text appears, is available to read in the gallery space. Ashberry’s vivid, fluxed poetic language is a good match for the works on view, which could be described as exercises in the de-familiarization of everyday objects and materials. And just as with Hans Holbein’s famous anamorphic skull in The Ambassadors (1533), one often needs to look at things from a certain perspective to see them properly.

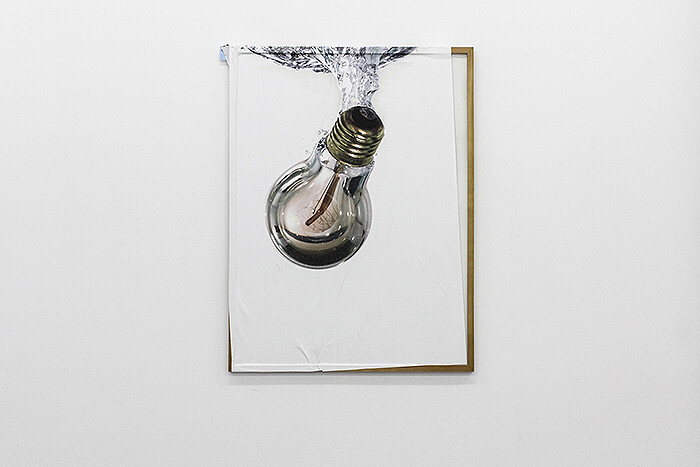

In her “Demonstrators” series (2011), Beier repurposes generic stock images—ordinarily stored in large databases and sold for commercial reproduction—by pairing these large, high-quality prints with carefully selected domestic objects. Two quintessential examples—the frame and the radiator—are shown here: in one, a poster depicting a light bulb submerged in water is stretched unevenly across a wooden frame, and in the other, the image of a frayed and broken rope folds smoothly into the radiator’s curves. According to the online library that licenses the rights to this image, the sinking bulb might relate to ecological disaster, and the broken rope to ideas of risk, weakness, or stress. (It is interesting to imagine what Aby Warburg would make of these archives had he lived in the digital age—stock pathos in times of liquid modernity?) The operation Beier performs on these images emphasizes their ambiguous meaning, and juxtaposes their uncanny hyperrealism with the reality and banality of the everyday. Eventually both image and object are estranged from their contexts and adopt new meanings. Wrapped in the poster and carefully cloaked in plastic, Beier’s radiator with its unconnected pipe surprisingly evokes a sense of warmth and the conservation of energy.

Floating on the floor like a rescue raft, Łakomy’s Fluffy Shell (2003–12), a sculpture made using a reconfigured Nike jacket, operates on a similar level. The stripped-back fabric arouses a sense of both comfort and vulnerability, as the dismantled item of clothing can no longer be worn. On the wall beside it, there is a second piece by the artist, Places Which I Like (2013), a sculpture made from Ikea shelves with pieces of thick, rectangular plywood sticking out vertically from the wall. Reflective foil covers one side of two of its elements, dreamily casting back a view of the white wall and half of the adjacent panel. The mundane materials employed in the sculpture suspend reality, operating like quotation marks, and enable the space of the form to open to the bodily experience of the here and now. Mickiewicz’s object, Slack side. A place for itself (2013), which is comprised of a generic, so-called “pouf” stool turned inside out, offers a similarly compelling invitation to introspection. The mute inwardness of the furniture resonates with an overtone of melancholia.

The potentiality of the inoperative quotidian object is a common thread linking the works presented in the gallery. Smith’s sculpture Untitled (2012) is a seat cushion resting against the wall with a circular hole at its bottom, revealing the foam stuffing inside. Its upper edge is stained with resin, a blemish that is abject not only because it somatically evokes mucus, but also because it strongly contrasts with the hole’s clean-cut precision. The only video in the show, screened on a monitor placed on the floor, is the artist’s Eggfeet (2011), edited found footage of a person cracking eggs into their shoes, and then placing their feet inside them. The image is wonderfully repulsive and absorbing. This ritual gives the impression of following a preset logic, whereby all the gestures are quite precise with the shoes placed on a tidy mat, and everything fitting into place. The act of putting on one’s shoes, one of the most familiar actions of daily life, is transformed into something uncanny. A sense of perverse pleasure pervades the work, because both feet and shoes are often fetishized in many cultures, and also because it is reminiscent of a guilty pleasure from childhood—that of playing with one’s food.

The sculptures in this exhibition operate confidently within the broad legacy of Marcel Duchamp’s readymade and reminded me specifically of his lesser-known Unhappy Readymade (1920), a splayed open geometry textbook suspended by strings on an outdoor balcony that exposed it to wind and rain. Mother Nature’s brutal treatment of the scientific tome is very much in keeping with a Duchampian mode of tongue-in-cheek irony. The purposeful distortion of the object brings about a shared melancholia; lacrimae rerum, or the “tears of things,” are falling in Galeria Stereo, much to the discreet pleasure of its visitors.