This spring, two interconnected exhibitions with the same title, “The Magic of the State,” were on view in London, at venerable commercial space Lisson Gallery (March 27–May 4) and in Cairo, at the fledgling not-for-profit space Beirut (March 3–April 6). Both shows featured the same list of artists—Ryan Gander, Goldin+Senneby, Rana Hamadeh, Anja Kirschner and David Panos, Liz Magic Laser, Christodoulos Panayiotou, and Lili Reynaud-Dewar—and an overlapping selection of works. The project, which borrows its title from a book by anthropologist Michael Taussig, presented artists drawn together for their shared interest in articulating or responding to the mechanisms of state power, and the high theatrics and tactics that endure across civilizations in seizing and maintaining such power. Each identified particular instances in which cracks in the armor of the state might be made—at moments of state formation, climactic political upheaval, or regime dissolution—and through which this certain “magic” might be glimpsed, glittering seductively.

Money, for example, was a form of magic that returned again and again in the exhibition, as a symbol once connected to the value of gold, and now loosened from any material connection. You want proof that magic works? Look at money. In fact, look at it “physically,” suggests the American anarchist thinker Peter Lamborn Wilson in the excellent publication Notes on the Magic of the State 1 which was produced following the exhibition. Anja Kirschner and David Panos’s film Ultimate Substance (2012), made in Greece, suggests that the formation of mathematics, algebra, and so on and the development of currency and coinage were tandem advancements in abstract thinking, which would eventually run free from human bodies and concerns to follow its own logic; whilst Goldin+Senneby both investigate the idea of “headless” money in their installation Money will be like dross: A replica instruction for the August Nordenskiöld alchemy furnace (2012), which creates a set of alchemical instructions which could potentially be carried out to make gold worthless in order to abolish the “tyranny of money.”

The following conversation between myself, Beirut (Sarah Rifky, Jens Maier-Rothe, and Antonia Alampi), and Silvia Sgualdini of Lisson Gallery, curator of the exhibition in collaboration with Beirut, took place in the summer of 2013, against the backdrop of political mayhem in Egypt, in which emails continually were blocked or went astray, while the discussion rose and fell in its urgency in direct relation to the subject under discussion. The way in which the state gathers and demonstrates its power using misdirection, sleights of hand, theatrics, violence, or bureaucratic or political processes that come close to being unsolvable riddles, are all important considerations in a country which is splintering into uncertainty, protest, revolution, and even extreme violence—and then again, these events can be said to reduce the imperative to create or discuss art exhibitions in favor of more direct responses and actions.

***

Laura McLean-Ferris: Let’s begin with your collaboration, in which an exhibition is shared by a commercial gallery and non-for-profit initiative in very different parts of the world. What brought your two ostensibly different art spaces together?

Silvia Sgualdini: The partnership was born from several conversations and experiences connected to a period of curatorial research in Cairo I undertook on behalf of the gallery, and was certainly a response to the continuous unfolding (or unraveling) of political events in the country after the revolution and the overthrowing of the Mubarak regime in 2011. I suppose it can be seen as unusual that Beirut hosted a project initiated as a collaboration with a commercial gallery in their institutional space—more common is that not-for-profit initiatives are invited to curate in commercial galleries. I personally think this was a very bold and uncompromising position on the part of Beirut as a not-for-profit institution (and one that has only recently started to operate). Perhaps it is also important to note that the project was funded both by Lisson and through grants that Beirut obtained from public bodies. I feel that the line between public and private, not-for-profit and commercial is nowadays extremely fluid, especially with the increasing restrictions in public funding, but at the same time it is still somehow taboo to talk openly and question the dynamics and shifting parameters of this relationship.

Beirut: In keeping with what we hope to stir up with Beirut, in the specific context of Egypt’s art and cultural landscape, the economy and politics of that, we like to imagine but also insist on how art can exist, be practiced, shown, circulated, and thought of outside of the external requirements that speak to how art is seen as means for self-expression, freedom, cultural diplomacy, or otherwise. Often art is considered a tool of “soft power,” which it may or may not be, but this in essence should not govern the impetus and logics of the why and how we work. Most funding for the arts in Egypt comes from the cultural development and diplomacy circuit, often European or American; locally there is little if any support for the arts, either from the state or privately.

LMF: So while state support might appear at first glance to be more ideologically neutral, these public sources carry with them an obligation, which demands that the exhibition perform as advertising or public relations for the state itself, or from the desires of other nations to collaborate and build relationships.

Beirut: To us, working together struck us as interesting and enabling in a different way. We approached a new type of collaboration that is somewhat stripped of a pseudo-benevolent essence maybe, with both institutions taking a different set of risks in committing to such a project for diverse reasons. It also is a touch cheeky the way that this idea has been received within our wider professional networks—with skepticism and wariness for instance—whereas we think this type of collaboration is perfectly reasonable, especially in its transparency. In fact, we would encourage stronger and more varied collaborations between for- and not-for-profit institutions within the arts across the world. It makes things possible and makes the economic reality of art in circulation a little more varied in certain contexts that lack public infrastructure and support for the arts.

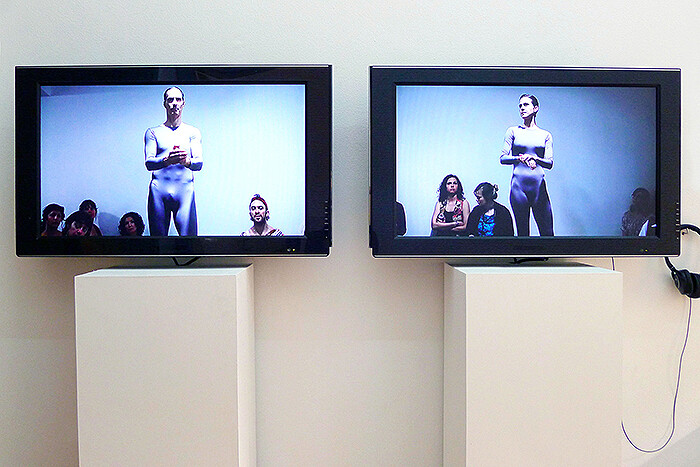

LMF: Something I thought was particularly impressive about this project was the diachronic scale of the inquiry, including the work of artists who are involved in a consideration of many different histories of state-building and an articulation of fundamental moments of change in the evolution of ideas. The exhibition was peppered with references to ancient civilizations in Greece, Cyprus, and Italy, alongside more recent demonstrations of the “magical” behavior of states. I’m thinking, for example, of the choreographic expressive gestures that world leaders learn to use as rhetorical techniques when giving speeches, which are relearned as choreography by dancers in Liz Magic Laser’s performative Stand Behind Me (2013), for example.

SS: I think what was interesting to me in the selection of these particular artists and works was the modalities in which they expose moments in the building of a nation’s identity that highlight the idiosyncrasies implicit in this operation, on which the state thrives but perhaps does not have a full consciousness of. They intentionally avoid relating a rigorous historical analysis of philosophical and political narratives in favor of navigating through these using mainly associative processes. I think this is where a certain fascination with magic came from; to capture, in a broad sense, these elements that escape a rational explanation and whose power is beyond their material presence. Magic also implies a different relationship to space and time, and therefore to history.

LMF: I thought one of the interesting things to come out of “The Magic of the State” was the concentration on moments of state-building—the way that several artists had attempted to trace back particular manifestations of state power to some kind of origin, particularly in the Kirschner and Panos film Ultimate Substance, with regards to the development of money; or in Christodoulos Panayiotou’s series “New Office” (2012), documentary photographs which trace the slow decoration of the presidential office in Nicosia, Cyprus, as it appears in the background of official photography; and Lili Reynaud-Dewar’s installation Cléda’s Chairs (2010), which plays with the idea of law or regime change, in the handover of furniture to the artist from her grandmother. And yet, the origins that were identified were as much about storytelling, mythology, and magic as they were about the technical developments of economics, laws, and bureaucracy. I thought this was a very interesting choice in that it made the state seem both weaker (a process that could be repeated or unraveled) and more powerful—as though the energy of a collective inevitably and automatically looks for something in which to invest its energy. Does this resonate at all with your ideas in conceiving this exhibition?

SS: Absolutely. It was particularly important for me to stress that a dichotomy between the state and the people is inconceivable and to rather focus on how the people are implicated in the building of state power—they become citizens in the process—and are therefore willing to submit to it. Fundamentally, power is understood as malleable and is involved in a dynamic of exchange between the people and the state. Now it seems like a crucial moment to look at dynamics of state formation, whether historical or mythical, and question the mechanisms by which power is vested into certain structures.

LMF: This was also a very humane exhibition about power, which is more often pictured as a kind of blank. I think Taussig sums this up quite well when he describes his book of the same name as an anthropology of “the state as a reified entity, lusting in its spirited magnificence, hungry for soulstuff.” At what point did Taussig become key reference for the exhibition?

SS: In regards to Taussig, I came across his book in the context of a wider research on magic, mysticism, and (political) power. I was already considering the work of some of the artists in the show, and I felt that his approach to the subject and his visionary reflections (although Taussig’s research was based in South America and had no connection to Egypt or the Middle East) were encapsulating exactly what I was trying to grasp in relation to the functioning of the state and its force. His particular approach to anthropology—in which he is implicated as a thinking and imagining subject—became more relevant as a key than a direct reference to political and state theories, although these inevitably underline much of the works in the exhibition and the texts in the publication. So, the exhibition is not a “homage” to Taussig’s book, neither an “adaptation” of it, but the thinking behind it is indebted to some of his ideas. It bears the same title of the book because it so marvelously brings together the lines of enquiry I was following, the formation and operations of the “state” with “magic.” It is wonderful that Taussig was enthusiastic about the project and agreed to come to Cairo to give a lecture that revisits his original book.

LMF: Could you, finally, describe Beirut’s decision to show work such as this in the midst of political upheaval in Cairo?

Beirut: At times Beirut is read as somewhat asynchronous to what is happening, and at others seen to be in perfect tune to why it is where it is. Upheaval is a time of revolution in process, of things changing, and people accepting this change, and being open to new things; it is also a time that necessitates hope, in both the optimistic and pessimistic senses. This moment in Egypt is witnessing a wave of new things happening, a claim to being, to having things a certain way, to demanding diversity, and this negotiation is met with protest and violence, but also with accepting the terms for a new Egypt, maybe.

Within that, Beirut would align itself with a wave of new institutions, or initiatives becoming institutions, which are grappling with questions of our discipline and how it can address all that is going on, how to relate and contribute to this moment of pivotal transition. It is also important as a vantage point from which to access and engage what is happening here without reducing the complexity of events to mere news: the fact that we can host artists, writers, thinkers, friends, respond to inquiries, keep an open access point of what is going on from the space of practice locally to the outside world… that’s of huge importance! This also contributes to the demystification of what’s happening… And of course, whereas the constant shift in the political and public landscape necessitates malleability, adaptability, and resilience, Beirut is absolutely necessary—both actually and symbolically, if not only for this current present and moment, then for Egypt in the future looking back.