Not long into a recent visit to Christine König Galerie in Vienna, I was overcome with anxiety. Faced with a lot of work by artists I’d never heard of, I felt a familiar, acute need for a press release to explain the clipped and cryptic “is my territory.,” the group show curated by a Berlin-based artist who teaches, nonetheless, in Vienna: Monica Bonvicini.

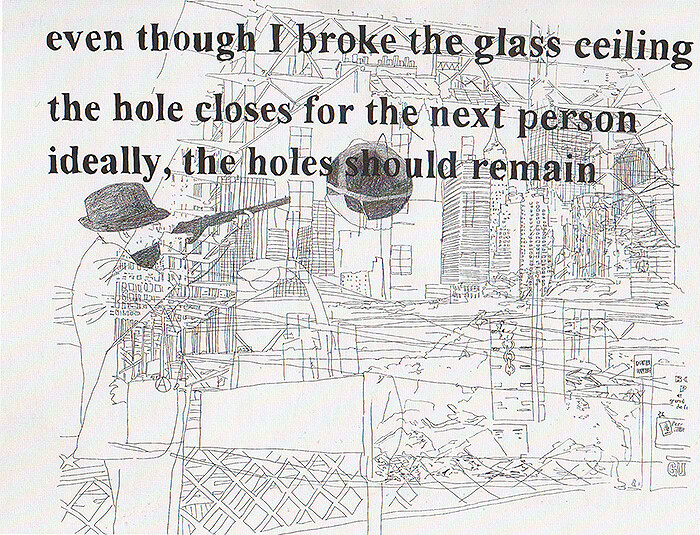

Attributed to a long list of seemingly unrelated writers (Johannes Porsch, Reinhard Priessnitz, Georges Perec, Virginia Woolf, Gertrude Stein, and Bonvicini), the abstract text—“‘I’ stayed a while. ‘I’ left and came back later”—only worsened my angst. But near the desk was clearly the exhibition’s centerpiece: a work by Bonvicini with Sam Durant, with whom she collaborated on her seminal “Break It / Fix It” exhibition in the Secession in 2003. Hole (2003) is a poster-like drawing depicting a man training a rifle at a large black hole in an outlined city landscape, over which a text proclaims: “even though I broke the glass ceiling the hole closes for the next person. ideally, the hole should remain.”

This, one expects, encapsulates what this exhibition is about—or maybe not: before it goes fully abstract, the text states that the show “represents a temporal, spatial and contentual (sic) overview of the ten years during which [Bonvicini] has served as Professor of Performative Art–Sculpture at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna.” The other artists on view are, in fact, exclusively women with whom Bonvicini has worked with or taught during her tenure at Central Europe’s oldest art school, some of them fresh graduates, others colleagues (which I could only find out later; the text was so vague that I had to return to the desk and get the work list, which at least had pictures).

Freestanding sculptures dot and dominate the gallery’s three rooms, like Cäcilia Brown’s steel-frame concrete-topped “table” (Untitled, 2013); recent Academy grad Gabriele Edlbauer’s hanging cylindrical sculpture called Radler (2013), which she bizarrely combines with a serving cart and sewn fabric lemons; and Julie Hohenwarter’s triangular steel floor sculptures (Ohne Titel / Untitled [Paris], 2013). But I was drawn to the show’s smaller, quieter works—in Danish artist Sofie Thorsen’s series “Play Sculpture” two simple line collages elegantly trace the outlines of playground structures that once existed throughout Vienna (no need for a viewer to know this; the pieces are lovely, calligraphic abstractions on their own); on the wall behind Hohenwarter’s floor shapes is a wall of flapping sheets of paper with short multicolored wax markings, similarly tracing intricate choreographies of, presumably, the streets of Paris. On the floor near the exit is a small clenched fist, chained to the radiator, from a series called “Fisting” by German artist Toni Schmale. Its fetishism is unmistakable, yet its unobtrusive placement makes it more sinister than confrontational.

Some of the work feels too underdeveloped for a commercial gallery show: a video by Anna Witt consists of still pictures of public political and artist interventions while a droning Viennese law enforcer on the soundtrack talks about what would happen legally to the “perps.” Other pieces are safe and derivative, like Stefanie Seibold’s shiny, “minimalist-inspired” objects or Maruša Sagadin’s posters collaging the names of the exhibition’s participating artists, a riff on an invitation card or album cover.

Bonvicini often uses spatial constructions and language to address gender and power relationships with great aplomb; anyone familiar with her work can identify echoes of her themes and forms here. But faint echoes don’t make for a strong exhibition, nor does its lack of focus. The red thread running through this show seems to be that all the artists are female, have worked or studied with the curator, and live and work in Vienna (which, when you’re not Austrian, can feel like its own impenetrable ecosystem). Issues of sexuality, gender discrimination, postmodernism, post-communism, and cultural identity rise to the surface, but they evaporate all too quickly: the exhibition, at best, becomes a reminder of what it might have been. Instead of a bold statement, it feels like a chick clique’s secret code.

Maybe Bonvicini chose the wrong works—or was given the wrong ones from her peers and students. Some web research reveals that several of the artists have broader vocabularies than one might infer from this show. For example, the young Estonian artist Kris Lemsalu’s Two silent instruments preparing to tour forever (2013), hanging accordions festooned with bricks and Legos, didn’t resonate with me here; while other sculptures in her body of work, including elements like ceramic tongues and fake fur, indicate a subversive sexual humor. Brown and Sagadin, too, have intriguing, often performative oeuvres.

Which makes the fragmented, open-ended “is my territory.” all the more a missed opportunity. If it’s about claiming one’s own territory—as a woman, as an artist—this exhibition could have more clearly underscored the status quo of feminist art in Austria. If, on the other hand, it’s just about Bonvicini’s alliances in Vienna, she could have done far more with what she has—dug deeper, found more cohesive connections, “leaned in” further, instead of “coming back later” (whatever that meant in the press text). If the “glass ceiling” reference in the 2003 work was meant to indicate that her professorship in Vienna broke it, one can unfortunately see that it takes as much or more effort to keep it open from the other side.