June 1–November 24, 2013

National pavilions can come in all different forms—naturally. Consider, for example, my first night in Venice, where I found myself at a grand palazzo for a dinner collectively hosted by Sadie Coles, representing England; Jose Kuri and Monica Manzutto, representing Mexico; and Gavin Brown and Barbara Gladstone, here representing the US (or New York, at least). The gallerists’ respective compatriots, and others, were well in attendance, isolating, aligning, and signifying among themselves, as nations and nationals tend to do. In the Palazzo Zeno’s beautifully crumbling courtyards and gorgeous baroque halls, archipelagos of small island nation-states arose.

Some on the scene, of course, pledged allegiance to a number of nations, including me. But everyone had seen each other recently, in Mexico City, London, New York, or elsewhere. And everyone was returning to those places after Italy. Thus their cosmopolitanism and nationalism went hand-in-hand: each person was defined not only by their well-traveled itineraries but by the nations they came home to and represented on the road. In this regard, the dinner that night mirrored the Venice Biennale’s eighty-eight national pavilions. Like the dinner party, the pavilion artists representing their respective countries were ostensibly if not exclusively (or really) doing just that; such forced nationalism, offering native “traditions” and hermetic singularity, is never quite that simple or coherent.

British Magic

Would it be embarrassingly Eurocentric to begin with the British Empire? Yes, alas. On my last night in Venice, on the vaporetto taking me back to the Lido, I ran into Peaches (Canadian, a Berliner). She told me—her grill flashing sweetly—that the Melodians Steel Orchestra, of London, was staying in her hotel, the Helvetica. “Ah,” I cried—“lucky.” The steel drum group, filmed recording a winning version of David Bowie’s “The Man Who Stole the World,” features in Ooh-oo-hoo ah-ha ha yeah (2013), the Jeremy Deller work at the heart of his fantastic British Pavilion English Magic. In the associative film, Range Rovers are crushed in the talons of junkyard machines while birds of prey spread their wings in green-screen-like flight and children bounce deliriously on an inflatable Stonehenge. It ends with the image of a pale falcon swiveling its head toward the audience, as though he were the spirit animal of the White Duke himself. Bowie’s song title is not unimportant either: Deller’s pavilion (perhaps best of show, if I may be so banal) features a menagerie of stories about contemporary neoliberal and royal thieves and magic animals par excellence: Roman Abramovich, Tony Blair, Prince Harry. In his essay for the pavilion’s publication, Hal Foster notes: “In the age of neoliberalism, Deller suggests, the truly potent magic is precisely this ability to turn public resources into private gain.”

But magic does not stray to the side of the thieves only. It is also carried by Deller himself, as well as the creative magicians he employs (Bowie, the Melodians, William Morris). Together they turn a bag of conspiracy theories and real political tragedies—the Iraq War, the looting of Russia, the killing of endangered birds of prey by entitled, obtuse royals, the yacht parking lot of Venice—into sharp, winsome tableaux of artistic currency and power. Deller’s empathy, eye, and political engagement are as pleasurable as his sense of humor, where such political sincerity often goes to die.

Taste or, Culture and Country

Surrounded by Massimiliano Gioni’s larger show, the somewhat airless “Encyclopedic Palace,” with its Documenta hangover of late, and serious crush on cleanly framed taxonomies, the national pavilions’ representatives of culture and country felt antique and obvious and a mess—but also a relief. Gioni’s turning of private cosmos and personal struggle into a stylized interior design aesthetic was definitively lacking in the disordered, disparate pavilions, where taste was usually the least concern. Yet lack of taste does not always equal distastefulness, which often arises instead from an excess of the stuff. If sometimes bad taste materializes as poeticized and/or politicized kitsch (see the pavilions of Canada, the US, Israel, and, at moments, the Netherlands), other pavilions broke through the visual chatter.

Take the Serbian Pavilion, which on first glance looked like a badly installed group show of insignificant works, then quickly drew me in with its alternately suicidal set-pieces by Vladimir Perić (a decorous wallpaper made of razor blades titled 3D Wallpaper for Bathroom, 2013) and life-affirming music videos of intergenerational antics by Miloš Tomić (Annual Musical Report, 2013). Or see the wonderfully provisional Georgian Pavilion, a plywood pile called Kamikaze Loggia, approximating the vernacular architectures that followed and amended Soviet architectural modernism. The day I visited, a performance by Gela Patashuri, Sergei Tcherepnin, Thea Djordjadze, and Joanna Mytkowska, among others, was in progress. As the latter two sang out a Georgian poem, the assembled crowd pounded the sides of the building, which Tcherepnin recorded and then broadcast (the sound of the building itself) over local radio stations. (The poem was written by one of the artists’ fathers, a working-class amateur poet who died in a construction-site accident.) Here the Socialist aims of creativity for all were not simply critiqued but celebrated, in a patently poignant manner.

Regarding taste, however, it might be more instructive to consider the German Pavilion (this year installed in France’s building for no substantive reason except for the novel idea of a pavilion swap), which initially struck me as embarrassingly transparent and ill conceived. German guilt was all over it: the five politically acute artists on view here included only one (French-Iranian) German “national,” Romuald Karmakar, who showed a deft, depressing film installation about a neo-Nazi rally on Alexanderplatz commemorating the end of WWII, as well as a work in which a German actor read a Jihadist speech. The other artists, Ai Weiwei, Dayanita Singh, and Santu Mofokeng, expertly represented a number of continents and serious critical practices. “This is an understanding of Germany as an active participant in a complex, worldwide constellation of influences and dependencies—not a hermetic unit,” goes the press release.

Around the pavilion’s central room, with a so-so installation of hundreds of three-legged stools tied together into a kind of web by Ai, the other artists were each given a separate space, where they showed subtle, probing works that beckoned forth the spectral ghosts that haunt our more material world. Singh’s surreally gorgeous black-and-white photographs and films of Indian outcasts (people, architectures, landscapes) troubled and spellbound as always. Mofokeng’s photographic series depicting black South African burial sites cut off by construction sites and mining inroads offered another disquieting view of neoliberalism and the relic-strewn landscapes it continues to assiduously colonize. A beautiful wall text by Mofokeng traced the issue of ancestors, specters, signs, and predecessors (evoking a less wry Deller): “Generally, ancestors need grounding, a landscape, or territory.” Artists too, one could imagine the anthropomorphized pavilions assenting.

Hard Architecture

A unique quality of the pavilions is that their success depends on how each artist handles their attendant architectonics. One of my favorite pavilions—architecturally—was this year a bummer of mirrored ceilings, rainbow reflections, heavy breathing, and a mildew-y smell. (Not a motel, surprisingly.) I wandered around Kimsooja’s Korean Pavilion in my socks remembering Haegue Yang’s wonderfully noir-ish installation of blinds four years ago. The Swiss Pavilion also provoked nostalgia. Bruno Giacometti’s austere, 1952 modernist idyll is one of the finest pavilions in the Giardini. If two years ago Thomas Hirschhorn obliterated Giacometti’s clean lines with his overwrought, über-hoarding installation, this year Valentin Carron erred on the side of caution, hewing too close and careful to those very same lines. Carron’s wonderful, eighty-meter-long iron serpent (You they they I you, 2013) slides sleekly through the rooms, barely making a dent in them. A series of decorative modernist-tinged abstract fiberglass paintings; a Piaggio Ciao scooter; and instruments flattened and cast in bronze and hung on the walls also made only the slightest impression. It was all tasteful, lovely, and smart, but a bit forgettable.

Romania fixed the problem of its soaring white cube by leaving it empty. The work in the pavilion—An Immaterial Retrospective of the Venice Biennale (2013) by Alexandra Pirici and Manuel Pelmuş—included live “reenactments” of past Venice Biennale installations. On the day I stumbled in, Sophie Calle’s famous break-up letter was being read aloud by a small, articulate woman. The audience looked alternately enraptured and dejected. In her discreetly powerful Spanish Pavilion, meanwhile, Lara Almarcegui also tread some familiar contemporary-art modes and ideas, though they were insistently material. And the pavilion was a natural: streaked with sunrays from the skylights above, the piles of stone, wood, glass, and dirt—the exact same amounts that were used in the building of the pavilion itself—were immediately comprehensible, inevitable, lucidly effective.

The Literary Arts

Cripplewood: I loved the title of the work by Berlinde De Bruyckere filling the Belgian Pavilion, the installation not so much. I admire J. M. Coetzee—who, literate, doesn’t?—but seminal writers and caustic, restive fabelists can make weirdly precious curators, casting about sentiment in a visual setting that they would quickly excise in their own more brittle and bracing literature. Perhaps it was the darkened skylights, the ashy walls, the enormous felled tree trunk, actually, explicitly bandaged. It was all a bit too nacht, too “woods at twilight.” (Too teen vampire flick, to be honest.) As mere words, “Cripplewood” is beautiful, touching; in “real” life, made material, it is saccharine, an illustration. Poetic lexical images need not be made visual.

Literature was picked up again, elliptically, in Lithuania and Cypress’s superb offsite pavilion, which turned an enormous modernist turnhalle hidden behind some crumbling facades into a kind of fictional world where poetic images came to strange and dreamy life. Its odd title—“Oo”—is defined as a “line with two sides passing through time, body, a life, and a country or two.” Maria Hassabi performed her intricate movement-based work on the steep, cinematic steps of the gymnasium, while far below, an installation of temporary walls made up of recycled walls from previous pavilions (by Gabriel Lester) and works by various artists—Jason Dodge, Elena Narbutaitė, and Dexter Sinister, among twelve others—looked, from above, as small and distant as a diorama.

Moving Images

Two national pavilions, distantly united by a shared colonialist past (as so many of the Biennale’s pavilions intractably are), turned out stunning new filmic works that limned the meaning of medium, remixing, and history in disparate ways. Akram Zaatari’s film for the Lebanese Pavilion, Letter to a Refusing Pilot (2013), departed from a mythic story he heard in his youth. During the Israeli-Lebanese war, an Israeli fighter pilot was instructed to bomb a building in Saida, the seaside city where Zaatari grew up. The pilot, an architect, knew the building must be a school or hospital from its design, and refused his order, dropping the bombs in the blue sea instead. As in Zaatari’s matchless past films (which also use that same blue sea to excellent effect), his new work mixes modes of visual storytelling: atmospheric fictive recreations are traded with formal investigations into the nature of images, surveillance, and memory, all while exploring the quiet urgency of ethical and national responsibility.

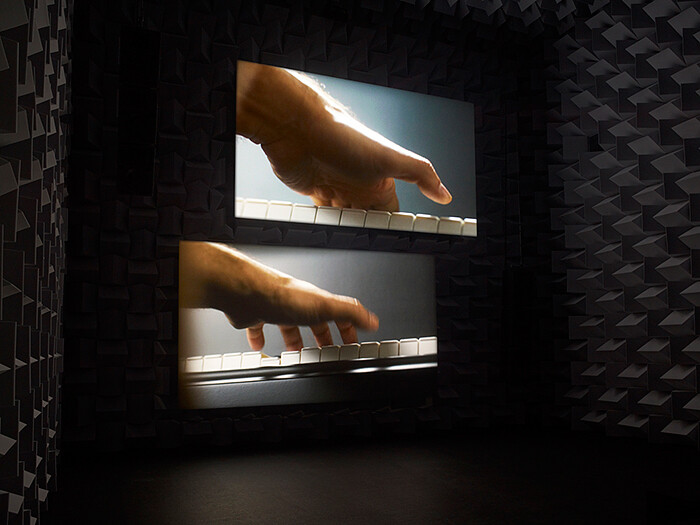

Meanwhile, Anri Sala’s French Pavilion (on view in the German Pavilion’s hulking structure), features a filmic triptych, which also explores a specific moment of history: the 1930 composition “Concerto in D for the Left Hand,” by the Frenchman (of Swiss and Basque parentage) Maurice Ravel. The wonderfully titled Ravel Ravel Unravel opens with a close-up of a female DJ’s face as she mixes something barely heard. In the next room, a soaring anti-echo chamber, her activity becomes clearer: the left hands of two famed pianists are filmed playing Ravel’s concerto separately and simultaneously (though not perfectly in sync). In the third room, a film shows the DJ (finally a full body shot) mixing these two performances in the space of the pavilion itself. The simplicity of the concept does not dilute the resulting work’s idiosyncratic power, which might come from the private artistic agency of the acts we are offered a strange window onto. In fact, as I moved through the Biennale’s pavilions over three days, a processing and procession of national and personal meaning seemed to test the walls of the architecture and institutions that held them. At times this created, as in Zaatari’s and Sala’s works, a new space between the borders of seemingly simultaneous states—personhood and nationhood, fact and sign, work and interpretation, experience and memory—evoking or articulating the strange travels (political, emotional, artistically generative) that take place between them.